Agile and the horizon effect

We work on each piece, not knowing whether or not disaster lies around the corner. We have to delay solving potentially tricky problems, and can never be really sure that the site will work until we’ve completed it.

The 1960s saw the first ideological skirmish in computer chess programming (and by extension much of the nascent field of AI) between two schools of thought: ‘brute force’ and ‘selective search’. Brute force methods involved looking at every possible position on the board, whereas selective search advocated pruning the game tree by ignoring moves that looked plain wrong.

With the hindsight of Moore’s Law, this was never really a contest. Brute force’s superiority was reinforced with each new clock speed, and this is how all chess programs work today. Each move is considered, as is each reply, and so on. A computer will typically analyse ~250 million positions per second, evaluate them all and choose the computationally best branch of play.

Early brute force machines were set to calculate all variations to a fixed depth, such as five moves. However, programmers soon found that this seemingly fool-proof method was still leading to some terrible chess. The cause was a phenomenon dubbed the horizon effect, whereby the losing move lay beyond the point at which the computer stopped calculating. A computer playing to a fixed depth may therefore set out on what seems the best path, unaware of the disaster lurking around the corner. Frustratingly, it even may ‘see’ the losing move but find a way to delay it by a couple of meaningless forcing moves, thus pushing it beyond the fixed horizon. Out of sight, out of mind.

For humans, the horizon effect isn’t much of a problem. Intuition plays a surprisingly large role in chess, and experienced players can vocalise when a position “feels like trouble” even though the fireworks may be a few moves off. Famous studies by Adriaan de Groot show that much of this intuition is based on pattern recognition, so that over time a skilled player builds a pattern library and, with it, an innate early warning system.

Programmers, of course, wished to mimic this intuition in computers, and did so by introducing a concept known as quiescence; in effect, a measure of a position’s stability. At the end of each variation, quiescence is calculated. If the position is placid (quiescent), the variation can terminate and work starts on another branch. However, if the position is still deemed to have danger in it, the computer is allowed to look a little further, until it again finds a quiescent state. Quiescence fills the role of the human’s alarm bells, and substitutes for the intuition that certain scenarios are going to need a bit more care to solve.

Any system where work is conducted to a fixed depth is susceptible to the same effect, and of course Agile is no exception. As we all know, Agile often doesn’t afford us a long discovery phase, and asks us to focus on short, practical iterations. This goes against a designer’s natural instincts; one of the more common complaints designers have of Agile is that it rarely gives us the chance to conceive an over-arching ‘solution’ of the problem space. The horizon effect again. We work on each piece, not knowing whether or not disaster lies around the corner. We have to delay solving potentially tricky problems, and can never be really sure that the site will work until we’ve completed it.

Although in theory Agile is comfortable with the idea of rework, the real world penalties are high. At worst, we might have to scrap a whole approach because of an unforeseen problem in a future iteration, repeatedly pushed beyond our horizons until it is too late. Try telling your clients that the last £10,000 they paid you were wasted and see how far theory gets you.

As good designers, we therefore need our own quiescence search. Just as the computer develops an intuition for choppy waters ahead, so must we. We build up a box of tricks to handle these scenarios: starting work on tricky stories early (while keeping it secret from Agile dogmatists!), pushing easier user stories up the chart to buy us time, and so on. But these techniques only come with years of experience. As with the chess player, we rely on pattern recognition, experience and skill to act as our early warning system and flag difficult stories in advance.

The more I think about Agile design, the more I’m convinced it needs senior staff. Send a junior IA into the middle of an experienced Agile team and they’ll struggle to keep their heads above water. With senior design staff still at a premium, I suspect many companies will have to compromise the integrity of either their user-centred design or their Agile processes. I’ll leave it to you to decide which is more likely.

The illusion of control

The Door Close button is a result of this pretence of control. On the majority of lifts it has absolutely no function since the lift is on a predetermined timer. However, tests show that users like the peace of mind.

If everything seems under control, you’re just not going fast enough.” – Mario Andretti

Control is a slippery thing. It’s important to our lives; we need it to rationalise and justify our decisions, but sometimes it’s simply beyond our influence. The well-known fundamental attribution error is a clear example of how we overstate human involvement in random events – in short, we don’t like the idea that we or, failing that, another human, are not in full control of a situation.

With technology this is particularly prevalent. When we are asked to to let a machine act on our behalf we become nervous if we don’t feel at least partially in control. One example of this is the excellent writing tool Scrivener which has an elegant autosave built in, running after every pause of two seconds. This ensures that flow, very important for writers, isn’t interrupted, but provides the peace of mind that reams of text won’t be lost in the event of a crash. However, even with this tight policy in place, Scrivener offers a force save mapped to the regular keyboard shortcut Cmd-S.

Gmail offers a similar redundant safety net when composing a new mail. State is of course saved in the background via Ajax but Google again allow users the comfort of saving at a point of their choosing.

Sometimes genuine control is not possible, in which case the answer can be to hide this from the user to keep them happy. Lift buttons are a classic example.

Lift / elevator passengers essentially volunteer to be shut inside a metal box suspended hundreds of metres off the ground. Not only that, but they abdicate responsibility for their safety to a computer. Few sane humans would be willing to do this on these terms. As a result, lift designers have to be very careful to ensure passengers feel in control of the system, even though in reality they have only partial control at best.

The Door Close button is a result of this pretence of control. On the majority of lifts it has absolutely no function since the lift is on a predetermined timer. However, tests show that users like the peace of mind of the Door Close button, providing as it does the belief that there is no element of the lift experience that we cannot influence. Ethically, there might be concerns that this is flat-out manipulation of users. However, situations where a little interaction white lie works to reduce anxiety of users, it’s probably acceptable.

Appendix 1: As it happens, some lift models do have an important role for the Door Close: enabling debugging modes for engineers. Certain button combinations (e.g. floor number + Door Close) activate express modes, stop the lift running, and so on. Other models use a lock and key to prevent public access to these functions.

Appendix 2: For more info, try Up And Then Down, an excellent New Yorker feature article on elevators, their design challenges, and a mildly terrifying account of Nicholas White, who was stuck in a lift for 41 hours.

First day at Clearleft

So yes, it’s official, the new job is with the lovely Clearleft.

It’s official, the new job is with the lovely Clearleft.

Just back from my first day, and I can officially confirm that commuting from Highbury will kill me. Therefore I’m also on the move to Brighton. London’s been fine to me, but I’m sure this is the right move: quality of life, walking to the office, the time of year, house prices. Lots of personal factors but mostly, of course, it’s down to the work. I’d be daft to pass up the chance to work with people this damn good, help out with dConstruct (and maybe Silverback), finally use a Mac each day, and many other things that make a web geek happy. Consider me officially chuffed, and thanks to the Clearleft guys for a splendid first day!

Pragmatism, not idealism

It seems daft for designers to reject the basic language of web standards and development. As an analogy, take reading music. As a member of a band, it helps to have an understanding of what it’s like to play other instruments; you don’t want to write parts that no one can play.

I’m currently taking a short break before starting my new job (more to follow on that).

Obviously I’m relaxing and enjoying the weather, but I’m also brushing up on XHTML andCSS so I can ditch Visio wireframing and start creating live prototypes. I had planned to use this blog as my sandbox, but to do the job properly would require PHP knowledge I neither have nor want, so I’ve dropped in the WP Premium theme with a view to perhaps revisit at a later date.

I’m rather overdue in making the switch, since Visio is increasingly obsolescent for modern user experience work. Aside from its limited functionality, the page-based format makes rich interaction design hard to document. Much like with Blogger (see earlier posts), I only stuck with it to delay the productivity dip I’d get from ditching it, so this seems the perfect time.

One effect of the move to HTML is that, although I’ll still remain a user experience specialist, I expect to become a little more hands-on and versatile. This is in line with the way I personally want to develop, and I’m sure it’s the way to create better websites. Iain Tate talked about his company’s ideal hire being a “creative mini-CEO” – perhaps this is analogous, if miniaturised. Clearly designers are more useful when they talk the same language as developers and business people; think the T-shaped model but stretching out on the z-axis too.

However, as I make this move, I do notice some tendency in UX for people to drift in the other direction, and claim the high ground of hyper-specialisation. Particularly this is the case with newcomers and HCI graduates. The more I interact with them, the more I realise they clearly know the right theory, but there’s an astonishing lack of knowledge and interest in living, breathing web design. HTML seems to be a dirty word, something left to the developers.

This can’t be right.

User Experience folks are already accused (mostly behind our backs) of a certain prima donna quality, stuck in our ivory towers of cognitive psychology, user testing and LIS. We certainly don’t need more of this. Perhaps it doesn’t help that Jakob is still very much the poster child for the academic HCI community. Much as I respect some of his work, he seems to be the sole gateway drug, as witnessed by neophytes swearing fealty to all he says, to the point of dogmatism.

It seems daft for designers to reject the basic language of web standards and development. As an analogy, take reading music. As a member of a band, it helps to have an understanding of what it’s like to play other instruments; you don’t want to write parts that no one can play. And isn’t that a perfect crystalisation of the user-centred approach anyway? Understanding our customers’ environments so thoroughly that our solutions are naturally harmonious?

I’ve talked to a number of people about this issue, whilst mulling over the change. Developers in particular seem to love the idea (for natural reasons: it brings them closer to designers, and vice versa). But I also think the leaders of enlightened web companies are increasingly looking for people who have the flexibility, the breadth of understanding to help them adapt. The future needs specialists, sure, and we can still fill those roles – but more than anything the future needs specialists with extra strings to their bow: midfielders with an eye for goal, singer/songwriters, designers who can get down and dirty with the rest of the web.

Learning to cook

As well as, obviously, the eating, I think I’m drawn to the alchemy of cooking. Getting the raw materials and following a recipe, however mechanically, is a quite fascinating thing

As with most people, when I get busy, blogging suffers. Instead, I’m unwinding by learning to cook. It’s been a long journey, levelling up on the slopes of Mt. Noob and now reaching the stages where I’m at least mildly competent.

Lessons learnt thus far: the sheer ubiquity of onions and garlic. What happens if you don’t watch your fingers when chopping said onions. The numerous types of vinegar (white wine, balsamic, malt, cider – I don’t even like vinegar). Why people spend £100 on a knife. The delights of thyme, parsley, cumin, turmeric, garam masala, bay leaves, parsley, oregano, rosemary, and many others. How to buy meat that isn’t pre-packed. How bloody expensive prawns, grapes, saffron and vanilla are.

As well as, obviously, the eating, I think I’m drawn to the alchemy of cooking. Getting the raw materials and following a recipe, however mechanically (I’m certainly not at the stage to remember them, let alone improve upon them) is a quite fascinating thing – seeing a concoction of unrelated, immiscible fluids emerge two hours later as a rather delicious casserole is remarkable.

My other surprise was just how much planning it takes. Getting all the right ingredients at the right time, particularly the perishable ones, takes dedication and an anticipation of where food will fit in with your week’s routine. It requires an application of Just-In-Time inventory that would rival a small factory. But yet, somehow, this hassle makes the whole process more rewarding.

What this all comes down to, of course, is an admission that I’m pushing 30. Now that’s out of the way, does anyone have any recipes to share?

The Fox goes shopping: cognitive dissonance in e-commerce

In short, the more opportunities we give them to introduce negative modifying statements, the less likely they’ll buy from us.

One of the most widely used metrics in e-commerce is conversion: simply a measure of the proportion of people who go from x to Sale, where x might be simply visiting the site, or perhaps adding something to the basket.

Of course, increasing conversion is generally a Good Thing because it makes big red lines point up and to the right. To achieve this wonderful state of affairs, e-commerce designers tend to focus on incremental improvements, hoping to push 17.0% to 17.3%, for instance. There are some straightforward means of doing this: tweaking help copy, clarifying calls to action, shiny Buy Now buttons, etc. And it works, but it’s far from sophisticated, and I think we’re missing a bigger trick here. For the last few days I’ve been playing around with the idea of approaching it from the other angle, and exploring the role of cognitive dissonance in the purchase process.

Cognitive dissonance is a tension arising when we have to choose between contradictory beliefs and actions. A classic example is the fable of The Fox And The Grapes. In it, we see our protagonist conflicted by a dissonant state which he then rationalises, much to his satisfaction.

Initial dissonant state:

Fox wants grapes

Fox can’t reach them

Resolved consonant state:

Fox did want those grapes

Fox couldn’t reach them

It’s ok, they were sour anyway.

Although written 2,500 years ago, this fable perfectly outlines our typical response to cognitive dissonance: we seek to resolve its tension immediately, in one of two ways. The easy way is to change the belief, usually by introducing a new one that modifies it. The hard way (much less frequently practised) is to change the behaviour that’s causing us the conflict. In our example, the fox took the easy way out, reducing his mental anguish by introducing a new belief: the grapes were sour.

The Fox goes shopping

The same process happens regularly in commerce (for example, I’d contend that both buyer’s remorse and store cards both have their roots in cognitive dissonance). Let’s say a potential buyer is about to spend £50 on a Super Widget. It’s highly likely they’ll experience some dissonance:

“I want a new Super Widget”

“£50 is a lot of money, I could buy Jake a new cricket bat with that”

Being human, our shopper will find this dissonance uncomfortable and want to resolve it as soon as possible. So typically a third thought is thrown into the balance, which will modify one of the existing thoughts. This will cause consonance and will result either in the purchase being approved or rejected. A negative consonant state could be:

“I want a new Super Widget… but I don’t know if this one’s the right size”

“£50 is a lot of money, I could buy Jake a new cricket bat with that”

Net result: no sale. A positive consonant state could be:

“I want a new Super Widget”

“£100 is a lot of money, I could buy Jake a new cricket bat with that… but I’ve spoiled Jake rotten this year, his old bat will last until next summer”

In which case, the Super Widget is bought.

A lot of the time, we can’t do much to bring about a positive modifying statement. It’s often intrinsically generated, based on one’s life circumstances (“I’ve earned it!” / “It’s OK, I’ve been to the gym a lot recently” etc). But we can do a lot about negative statements, because a lot of the time we simply hand them to our users on a silver plate. People with biases look for means to confirm them. And by forcing them to surrender their details before the appropriate juncture, giving them tiny photos, burying our phone numbers, we make it all too easy. In short, the more opportunities we give them to introduce negative modifying statements, the less likely they’ll buy from us.

I’m sure I’m not the first person to have thought of this, but looking at things from the other side can reveal facets previously hidden in shadow. So here starts an experiment: rather than focusing on increasing sales (in effect, pushing people into purchasing), I propose we’re far better off removing the barriers that prevent them. It seems to me a more humanistic, less sales-driven approach, and one I think is better for us all in the long run.

The death of page views, and why we should care

Ask any web geek and they’ll tell you that the page, as we know it, is terminally ill.

Ask any web geek and they’ll tell you that the page, as we know it, is terminally ill. For many years, it was the proud atom of the web: an unbreakable, fundamental unit. However, much like the atom, it has now been broken down further, and in modern times is being bypassed by Ajax, Flash, desktop widgets, APIs, and RSS.

This breakdown of the atomic structure of the web is, in principle, laudable since it opens the door to a Semantic future. However, it causes at least two sizeable issues: first, the question of how we plan, architect and design this new world, and second, the impact on how websites make money. I’m going to focus on the second for now; the first is another post altogether.

Millions of commercial sites rely, of course, on advertising, for which page views (PVs) have been the predominant measure for years. Crude though PVs may be, it’s fair to say that if lots of people looked at lots of pages, your site was a good proposition. Same principle as why a TV ad during Corrie costs a lot more than one on UKTV Style. However, the page no longer means what it once did so, as the page dies, the PV goes with it.

The web advertising industry has yet to find a suitable replacement. The auditing companies (ComScore, ABC, etc) are of course striving to find a suitable heir to the throne; unfortunately, the obvious choices each have disadvantages:

- Time spent per visit can be heavily skewed by the type of site, and can’t cope withRSS.

- Unique visitors can’t differentiate between a passing glimpse and a whole evening spent browsing.

- Click-through rate generally isn’t very appealing to advertisers who are looking to build brand awareness rather than get direct response.

So there’s a good chance that we’ll end up with a hybrid measure that mixes these ingredients with how much users are actually doing on the site. So far this equation has been lumbered with unpleasant, mechanistic labels like “engagement” or “attention”, or clunky acronym (I’ve heard recently of the “User-Initiated Rich Media Event” – yuck). Whatever we call it, this magical new measure will quantify how much people are interacting with the sites they use.

And this is why I’m worried. There’s always been something of a creative tension between maximising advertising bucks and acting in the best interests of users. To earn the cash, a site should increase PVs by splitting articles over numerous pages, hiding content deep down in navigation, and so on. However, this clearly isn’t good news for the user. The recent Guardian redesign, for example, has been accused (fairly or unfairly, you decide) of maximising page views at the expense of findability. It’s an emotive issue, to say the least. (As an aside, Merlin Mann has a fantastic solution:

“Thank newspapers for paged site content by sending subscription checks in 10 torn pieces. Y’know. For convenience.”)

My concern is that if the primary commercial measure of a site’s success won’t be page views, but user interactions, this broadens for the scope for evildoing. Bad practice won’t be restricted to nerfing navigation and adding unnecessary pages; site owners can now inject this nastiness into the page itself. More mouse clicks, more reveals, more forcing the user to request information they ought to be given straight up. In short, an interaction design nightmare.

Sure, it’s self-regulating to an extent. A site that takes the piss won’t have users for long. But if a site owner can double her revenue while losing just 10% of her users, will she be tempted? (And would she really be wrong to do it? Yikes.)

This, to me, is a real challenge the web design community needs to shout up about. It’s easy to consider it as purely the domain of advertisers, commercial managers and auditors, but as with so many things if the user isn’t considered in this process we could end up with a system that encourages sites to act in a very user-hostile way.

Postscript

It’s tempting to say, ultimately, there are big question marks over sites that rely purely on an advertising model. Perhaps. I think certainly it’ll take a couple of years for the less smart advertisers to accept the demise of the PV model. Maybe, as a result, the next few years will favour subscriber models, while ad-supported sites gently stagnate in an old PV model until the industry catches up.

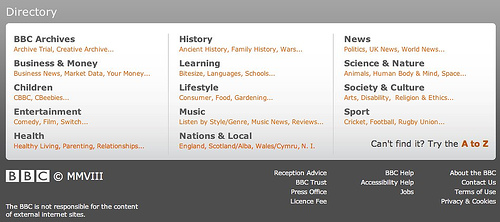

Functional footers are the new black

Seems that quite a few sites are now getting rather bottom-heavy and, you know, I think I quite like it.

Time to share a current geeky web design crush: big footers. Seems that quite a few sites are now getting rather bottom-heavy and, you know, I think I quite like it.

There doesn’t seem to be a name yet for this type of expanded area of functionality. Ho hum. I’m calling it a ‘functional footer’ until someone comes up with a better term. Regardless of the name, this fad actually makes some kind of sense:

- The fold doesn’t matter so much any more

- Obvious SEO benefits

- Logical spot for backup navigation if all else fails and the user is truly lost

- As resolutions increase, we don’t need to be quite as frugal with screen real estate

- Useful way to clear the navigational decks – if business owners are insisting on a particular link being available, a functional footer is a great place to put it so it doesn’t impinge on the main visual space

- Wishful thinking perhaps, but I do hope in some small way it encourages fuller all-the-way-down reading by users

- Rounds off the page nicely

What can I put here?

The really interesting bit is that some sites are mixing it up and going beyond the typical legal / contact / careers links. Blogs are adding links to previous posts, popular posts, “about me”s. Some are getting creative and repurposing some typical sidebar content – del.icio.us links, Flickr thumbnails (I really like this one). At the extreme end, the new waitrose.com has its entire sitemap in the footer.

Standard design disclaimer applies – ‘it depends’ – it may not work for your site, but it looks like it’s worth a shot if you’ve a lot of content and not enough space.

Old interfaces die hard

One thing bothers me about Bill Gates’s assertion that touch interfaces will be all the rage over the next few years.

One thing bothers me about Bill Gates’s assertion that touch interfaces will be all the rage over the next few years.

Let’s start at the beginning. Gestural and touch interfaces are absolutely nothing new. Here’s some of Bruce Tognazzini’s concept film Starfire, made at Sun in 1992. (Quite amazing just how much great stuff there is in here, dress code aside).

Not a giant leap from Starfire to reach Microsoft Surface.

Honestly, Surface gets attention mostly because it looks great. Really great. It’s elegant beyond anything Microsoft have ever done, and has that futuristic appeal that causes lazy journalists to spawn lazy phrases like ‘the Minority Report interface’. However, as any interaction designer will tell you, these kinds of interfaces simply aren’t as successful as they should be.

First, tactile response, or lack thereof. Example: a button has a satisfying ‘click’ when you depress it. A brake pedal resists the harder you push it. The right key fits snugly into the lock. A touch-based or gestural interface doesn’t do this, because there’s no direct feedback. The iPhone keyboard, while a remarkable achievement, is a long way from perfection. Fingers obscure the view, and there’s no feel for where one button ends and another begins. So in reality, it owes much of its success to its excellent autocorrection. For SMSs, it works beautifully, but have you ever tried typing in a tricky URL? It’d be quicker to type it in Morse Code.

Second, waving your arms around is seriously hard work. Play some Wii Sports, or conduct an orchestra for an hour and you’ll agree. Interfaces like Surface and Wii simply require far too much effort to be usable for long periods. The Minority Report interface needs grand, full-scale movement. Sure, you could downscale it, but haven’t we done that already with the trackpad?

Subtle, well-considered gestural interfaces will become more prominent, but I really do think the mouse and the keyboard will be our predominant input devices for years yet. They’re simple, cheap, reliable, require minimal effort and can be used in a number of environments. Eventually, sure, they’ll die out. I don’t know what will replace them (and if I did, I’d be rich), but I’ll stick my neck out and say it won’t be the surfaces of giant LCD coffee tables.

The Aiwa Facebook: £149 at Currys

Nice Facebook analogy from Iain Tait: Facebook is an all-in-one stereo system - fine for beginners but ultimately a bit limiting and of mediocre quality (web 2.0 is separates, natch). See also Wired's article Slap In The Facebook.

This was also one of the recurring themes at BarCamp Brighton, particularly with such a strong Microformats and semantic web flavour pervading the whole weekend. Lots of bold words about Facebook's inevitable (albeit it far-off) demise.

Although in principle I agree, I thought this was a little strong - I'm still rather ambivalent about it all. Facebook's certainly a useful tool and it's great to see so many people contributing to the web, sharing media and so on. I just regret that there's this great big mainstream love affair with a walled garden concept I hoped the web had outgrown.

Of course, the interesting question is how those of us nearer the front of the curve can convince our less geeky friends that separates are better, without sounding like horrible snobs. Believe me, I've tried, and believe me, I sounded like a horrible snob.

Why become an information architect?

I can't remember where I heard it, but I was surprised it came from someone in the field. The sarcastic tone surprised me even more than the chuckles of agreement.

Hang on, I thought with astonishment, surely we've not reached the stage where we reduce ourselves to hackneyed self-criticism? In my experience, passion for their craft is common to every IA, and it's one of the few careers you can't really 'phone in'. So, it's taken me a while, but for the record here is my response.

[Note: Yes, some of what I'm talking about could be called interaction design, user experience etc. Change the post title if you like. I'll leave defining the damn thing to others.]

It's creative

Every job has its drudgery. I'm sure some IAs would say that churning out wireframes comes pretty close sometimes, and certainly it can if you allow yourself to drift on autopilot. But any job that pays you to think and to listen, then to turn that into something meaningful, usable by everyone but retaining one's own creative influence, is a rare thing.

It's important

You're making decisions that can have a lasting effect. We all know that bad site > unhappy users > no revenue, but IA can matter beyond the realms of the bottom line. I have true respect for IAs working, say, on medical information sites, improving access to information that can change (or even save) lives.

It's varied

IA undoubtedly can lay claim to some of the largest changes of scale of any job in this domain. You may be looking at wide strategic decisions affecting thousands (millions, if you're with the big guys) of people. Or you may be arguing whether 18pt leading is appropriate for this type, or whether icon A is sufficiently differentiated from icon B. I've spent mornings looking at numerous shades of pea green and drowning in a sea of RGB hex, followed by afternoons trying to convince others that semantic markup should be a central platform for our business.

It pays

Salaries are going up, and not showing many signs of abating. This is a specialised profession in great demand. Of course, we will have to wait and see how it survives the next tech dip, but even the IAI's year-old figures are pretty impressive.

It's part of something bigger

This, for me, is what seals it. The chance to help create the future of the web, to create a shared language of interactions, of new features and that wonderfully vague world of 'cool stuff'. Things that will turn a sceptic into an ardent supporter. Sure, of course I'm here to make money for my employer, but ultimately I think I'm also here for the greater good - to make the web a better place. And because the industry isn't at 'idea saturation point', in a small way I can help to shape the whole industry. How many accountants can say that?

Perhaps this all needs to be balanced with the negative aspects. Perhaps that's another post. But try adding the prefix "Only you know" before any of the above headings for a flavour.

WordCount

I rediscovered an old site I'd meant to post about long ago: WordCount. It's another of those interesting visualisation tools, this time showing the commonality of English words. Derived from Oxford University's British National Corpus of 100 million words, it's an obvious practical example of the long tail. Since we get by on an estimated average vocabulary of 21,000 words* (compared to the 86,800 in Wordcount), there's plenty of undiscovered material to play with.

Aside from the interest derived from simply playing with it and learning more about our language, some wags have created games from forming sentences from words appearing consecutively in the list:

"Despotism clinching internet" (seems somewhat prescient of the net neutrality debate)

"America ensure oil opportunity"

"Apple formula: imagination"

Or, of course, you can play the slightly smug vocabulary-testing game, by testing your favourite obscure word and keeping score. Me? I started with a mediocre 'abstemious' (61282nd) but quickly followed it up with an impressive 'ziggurat' (83305th). No triple-word score sadly. There's also QueryCount, which is an exploration of the most frequently sought-out terms, and is of course considerably more profane.

Of course, sites like this don't really have a purpose per se, of course, other than exploration. But isn't it nice sometimes to release ourselves from the current task-based focus of the web, and get back to good old-fashioned surfing?

* For an alarmist aside, read Are iPods shrinking the British vocabulary?.

'This is a Unix system!'

Jakob Nielsen’s clearly in the holiday spirit, since his latest Alertbox is an exposé of the 10 biggest User Interface bloopers in films, which we’ll all see countless times over the next few weeks.

I’d forgotten all about Jurassic Park, where a 12-year-old girl saves the day and stops the usual rampaging dinosaur hordes through her knowledge of Unix. Gripping stuff, I'm sure you'll agree. However, there is one Jakob missed: noughts and crosses as an allegory for Mutually Assured Destruction. WarGames, of course.

Admit it, you’ve seen it. But, if your memory isn’t so fresh, WarGames sees teenage hacker David (Matthew Broderick) poking around WOPR, your typical global nuclear defence mainframe. Sadly, sloppy information architecture (seen above) causes poor David to inadvertently trigger global thermonuclear war – although, in WOPR’s defence, it does at least offer a confirmation dialog.

Realising his rather egregious error, David quickly stabs away at Ctrl-Z, but WOPR is having none of it. He can’t even shut it down through Task Manager. In the end, he has to rely on a cunning hack. By forcing the computer to play noughts and crosses against itself repeatedly, David causes WOPR to realise (in a flash of logic that somehow drains electricity from surrounding appliances) that the Nash equilibrium for global thermonuclear war is to not start it. WOPR smugly declares “the only winning move is not to play” and cancels the missile strike.

A close call indeed. And that, kids, is what happens when you don’t do user testing.

Mobile TV – not quite yet

Just upgraded to a Nokia N73. Very nice it is too. I've pretty much come to expect good usability from Nokia - I loved their older phones and they do an admiral job of keeping complex phones as simple as possible.

Anyway, it being a 3G handset, Orange are desperate to foist 3G content on me. So I have two months of free mobile Sky Sports TV, and unlimited off-peak browsing (meaning I'll be spamming the lovely Flickr upload feature whenever the photographic urge takes me).

So, my first foray into mobile TV... Well. It's a great idea, but the quality's just too damn low right now. Massive compression, glitchy visuals, and nowhere near enough detail. For the Ashes, it's better than Test Match Special, but not by much. I can pick out a Warne leg break, but there's no chance of seeing Hoggard swing it, although, based on the last Test, you'd struggle to see that on a 42" high-definition screen.

But, oh well, it's a start. It will get better soon enough. Google think an iPod will hold all of the world's TV programmes in 12 years. Interesting, but I think the bigger issue is that TV programmes won't exist in a format we know by then. As the long tail grows and convergence and YouTube continue to flatten everything in their path, where's the line between 'a programme' and 'visual content'?

Grasping the obvious, the BBC bleat "Online viewing eroding TV viewing". Yep. It'll erode it so much that they'll be the same thing soon.

But not yet.

You can’t Have Your Say and eat it

Interesting article on the BBC site: "Web fuelling crisis in politics". As a rule, I tend to find any government proclamation on the state of the web patronising at best, dangerously ill-informed at worst - but, for once, I'm in agreement. I find the majority of political blogs little more than infantile, partisan nonsense. This is normally countered by the stultifying suggestion that one can achieve a thorough knowledge of a topic simply by reading two contrasting and equally biased pieces.

This isn't confined to new media of course - news orgs are largely the same and, yes, I'm quite aware that the paper I read (Guardian, natch) is guilty too. But there, opinion should act as the starting point for debate. As Ben Hammersley has said, no one buys newspapers for news any more. The web and 24-hour news channels will always be first for immediate unfolding reportage. Newspapers have to reposition themselves as channels for editorial and debate.

The news orgs that 'get it' - Guardian, Telegraph, BBC come to mind - are starting to open up in this way. Sure, the results aren't pretty (particular the latter - Have Your Sayis home to some of the most rabid prejudice and catfights I've seen) but at least they're starting something genuinely interactive. I don't see political blogs doing the same, despite the rhetoric of two-way communication and citizen activism. Instead, I only see the negativity and criticism that seems to blight our perception of politics.

Cynicism is healthy in small doses, but sometimes I think politicians get it right. It's time to move on from the name-calling and sniping, and start using the citizen's new voice for positive benefit.

Understanding comics

I don’t like the word seminal. Besides its dual meaning, it’s a lazy, overused shorthand. But I would grudgingly apply it to Scott McCloud’s 'Understanding Comics', which I’m currently reading after many months on my ought-to list.

It’s as excellent as I’d heard, with some fascinating concepts on abstraction, graphical representation of time and motion, and icon design. Most impressive is a chapter on 'The Six Steps'. The creation of any work in any medium will always follow a certain path: a path consisting of six steps:

Idea/purpose – the impulses, the ideas, the emotions, the philosophies, the purposes of the work. The work’s content.

Form – the form it will take. Will it be a book? A chalk drawing? A chair? A song? A sculpture? A pot holder? A comic book?

Idiom – the “school” of art, the vocabulary of styles or gestures or subject matter, the genre that the work belongs to. Maybe a genre of its own?

Structure – putting it all together. What to include, what to leave out - how to arrange, how to compose the work.

Craft – constructing the work, applying skills, practical knowledge, invention, problem-solving, getting the “job” done.

Surface – production values, finishing - the aspects most apparent on first superficial exposure to the work.

My first thought was just how close this was to Jesse James Garret’s marvellous 'The Elements of User Experience' diagram. There are clear parallels – particularly the importance of strategy and choosing the appropriate medium, rather than jumping straight in to the visual layer. Ready, aim, fire.

McCloud talks too about how most newcomers start at point 6, then gradually realise the value of starting earlier through the process as their expertise grows. It’s the same issue that prevents information architecture being appreciated more widely: the “I can do that” syndrome, by which any untrained observer thinks that by merely replicating point 6 they can create a work of art. Hacked copies of Dreamweaver and Photoshop do not a designer make.

It’s great to see these issues talked about outside of the contexts I’m familiar with, and I’d love to learn more. Sadly I can’t make the day Scott’s presenting at NN/g’s User Experience Week 2006 (although I am going to the previous three), but I really hope he makes it to Page 45 later in the year as promised.

While I’m on the topic, this is King Cat by John Porcellino. [CB 2018: not the original image; this issue likely published after this post was written.] I was introduced to King Cat by a friend, who in turn was introduced by a friend, and so on. I try to continue the chain where I can. It’s probably the one title that got me over the comics-are-just-superheroes-and-fantasy hurdle, so I’m immensely grateful to it. The stories he tells are genuinely contemplative and sensitive, his drawing sparse yet lively – as much about space and omission of detail as what it portrays. Oh, and his animals are superb: Picasso dogs with jaws at obtuse angles, crayfish with pliable legs and squirming bodies.

To read King Cat is, for me, to be touched by a brief glimpse of the beauty of the world – which I something I think very few other media could achieve.

'My Very Excellent Mother…'

In which an astronomical trifle sends Cennydd into an orgy of arcane library science and obscure bands.

The hunt is on for a new mnemonic as Pluto is confirmed to, in fact, not actually be a planet, because it’s too crap. It’s your age-old classification problem: the item on the fringe, the one that makes you question your entire classification system.

Case in point: I bought a CD by !!! a while back. It’s poor, I can’t recommend it. More importantly, it caused me untold hours of frustration and grief. Should its punctuation mean that it precedes A? If so, does this mean I have to reclassify …And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead? And if so, which band comes first? Would this mean I would end up classifying by the ASCII character set?

Or should it go under C? (It is apparently pronounced “Chk chk chk”). Does that mean I’m now classifying by phonetics? Shaky ground, particularly when you’re dealing with bands called Xiu Xiu, OOIOO and 90 Day Men.

For a while, I actually started classifying my CDs by colour. While it satisfied the aesthete in me and worked fine for "driftnetting" browsing behaviour, it's useless for known-item retrieval. It's also incompatible with our mental models: we don’t tend to think in terms of “I’d like to listen to some purple music today”.

Some people rebel against the ideas of genres, but I can live with them. I don’t find myself offended by the labelling a large section of my collection “post-rock” or “shoegazing” or whatever. People who get offended by labels are generally more interested in listening to 'the right music' than listening to the music. But even that’s troublesome for the bedroom librarian. Where does one genre end and another begin? What about bands whose sound has evolved over the years?

Don’t even get me started on split EPs, or the Calexico/Iron & Wine collaboration. And do El Guapo go under E or G? Is the Spanish definite article to be ignored? What about Les Savy Fav? Is their name French or English? Should I be using ISO 639-1 to define it?

And this, my friends, is why iTunes is great. Don't like the way it sorts alphabetically? Browse by genre! Look for all songs under 2 minutes long! It's probably the most useful Ranganathan-inspired analytico-synthetic faceted classification tool I know of.

The real value of blogs

Old news really, but some bright spark has been fiddling with the Technorati API to calculate a dollar value for blogs. It’s based on the same $-per-link ratio as AOL’s recent purchase of Weblogs Inc. Cynics of course point out that AOL are great at spending pretend internet money.

Anyway, down to hard cash. This blog is worth $560, and my personal blog is worth $1,700. Not bad for blogs that as yet have no ambitions of mass readership. I’m having an eBay clearout at the moment – anyone want to buy the rights? A film deal maybe? I think Jude Law would be great for the lead role.

Now the serious bit. Blogs are a classic example of an intangible asset, a central theme of knowledge management (something that, for instance Karl-Eric Sveiby is very interested in). Some blogs are deep-freeze knowledge, thoughts and ideas encapsulated. Some present huge brand value, for instance Robert Scoble's. How much is his blog worth to Microsoft? $2m, says the tool. Personally, I’d put a higher price on it. Particularly for a company like Microsoft whose standing in the geek fraternity is not good, it’s a positive example of how blogs can present a uniquely human face.

Browse through the readers' comments to see what I mean. Some are positive, some are hostile, but all give Microsoft (through Robert) a chance to reply directly in a language customers understand. Surely that's what all enlightened companies should be seeking to do in this increasingly demanding market?

Web 2.0? Try Web 1.1

They say in the music industry that you know when a scene is past its peak because it makes its way into the mainstream media. I can't help feeling the same way about this Web 2.0 malarkey.

Newsnight had a remarkably accessible intro to Flock last night, and touched all the usual 2.0 bases (Flickr, Wikipedia, del.icio.us) without actually mentioning them by name. And, yes, it was interesting to see these new technologies presented to the public. But I still can't shake the feeling we've seen it all before. Groups of techies with laptops pulling all-night coding binges? The "hey, this is going to change everything" vibe? boo.com, anyone? The revolution that didn't happen? I may have been a tender 18 during the first dotcom frenzy but I recognise hype when I see it.

To me, Web 2.0 (God, I hate that phrase) is just the web reverting to its natural state. Like a stress ball after you let go, or the way you feel after taking off those trousers you no longer fit any more.

The early web was seized by mainstream media as another way to pipe content into everyone's life. Misguided? Sure. Understandable? Sure. 2.0 is about realising that the web isn't shaped that way. It connects people without the need for centralised content producers. Hell, that's why it's called the web.

And that's it. It's interesting, it's even exciting, but it sure as hell could do without the hype.

More:

The Web is equal to pi

The amorality of Web 2.0

Our Social World

[The following marathon post is based on live notes made at Our Social World, re-edited for context, readability, and for something to do on the train. It's more of a rundown than an opinion - the added value will follow in later posts!]

The experiment begins - WiFi-enabled laptop hastily acquired and at the ready. First thoughts are that the audience is, frankly, exactly what I was expecting. Mostly male, younger than your typical seminar crowd, a lot of Macs, some with personalisation: Flickr and Technorati stickers mostly. I've already had to give the blog elevator pitch to the taxi driver on the way over. Becoming quite proficient at it now. Probably make a post about it later.

Instantly, an interesting fact crops up: get 7 laptopped bloggers round a table and they'll all check their Gmail and not talk to each other all that much. So much for blogs enabling conversations, and God help us when the cricket starts.

Ben Hammersley is apparently the only living person to get a word (podcasting) into the OED. I don't believe that for a second. Sticking with a historical theme, he namechecks the blog A-list from 300 years ago, deeming Sir Richard Steele the first blogger. What about Pepys? Ben believes that the magic formula is:

Amateur publishing + coffee = Social revolution!

(accompanied by mandatory Che picture). His essential premise is that blogging is pamphleteering++, and I'd say he's pretty much spot on, which is why it appeals to those with something to say, and far less to the rest. However, there are some differences: a larger sphere of influence, hypertext capability, searchability (as opposed to the hordeing of printed materials) and, primarily speed.

As later speakers point out, Ben is a journalist and as such takes the journalistic angle. Revolution is in the air! You can almost see the glint of the guillotines. "The freedom of the press belongs to those who are free to buy a press," he says. "Well, we all have a printing press now!"

Simon Phipps is the brave soul responsible for the birth of blogs.sun.com. Of course some Sun-isms eke out: we're in the participation age, it's now the norm (not something cool) to be online, and this process has taken just ten years. Simon makes some excellent points about trust: we're now in a society that fundamentally mistrusts, so it's probably a bad idea to leave blogging to the PR professionals. To kick-start this at Sun, Simon had to reverse a policy that said you'll get sacked for talking about work.

"Your number one task is to write a blog policy." He also claims (correctly) that referrer logs are essential, as is the freedom to link anywhere, talk about the competition positively, admit failure and, goddammit, to tell the truth! The topic strays onto mainstream media. "You don't buy newspapers for the news. You can get news for free. You buy it because someone else has decided what you want to read - editorial view rather than content" (I paraphrase). Gasps from the media types in the room, but probably just because they know he's right.

Main topic thus far has been Daily Mail-bashing (yep, this is a liberal crowd), and the word 'bullshit' has cropped up several times. Great stuff. Out to the cricket - Eng 325-8. Not great on what looks like a 400+ wicket.

The BBC's Tom Coates gives an excellent talk on Social Software. The 'old' internet - IRC, email, Usenet, mailinglists, messageboards, MUDs - was designed to be participatory. It wasn't until the WWW that it all went askew and ended up as a broadcast and commerce medium. Tom attributed the return of the pendulum to blogs and Amazon (personally I think of old-school personalisation as a notable failure so I can't agree). There follows a brief demo of latest BBC R&D: Phonetags, where the public texts in when there's something on radio they like. They can then come back and review, tag, etc, thus providing the BBC with free folksonomic metadata. Similar is audio collaboration: allowing the public to comment and wiki-ise audio files.

From these great ideas, the conversation moves to the hoary old spam problem. How do you make social systems that aren't spammable? The general consensus? Um.. dunno yet. We're trying. I suspect whoever solves that will become very rich.

Johnnie Moore talks about "chaos and engagement". After a free-form drawing exercise, we hit the first truly controversial point of the day, Johnnie’s blog 173 Drury Lane, a consumer-driven blog about Sainsbury's started mostly out of curiosity. Some debate around the room regarding how Jamie Oliver's favourite corporation would react? Johnnie assures us they’ve not sent round the lawyers yet but, astonishingly (to my mind) there seems to be a body of opinion that they’d be justified to do so. Anyway, read the blog and make your own mind up.

Lee Bryant tackles the thorny “folksonomy v taxonomy” debate. Lee’s most interesting point is that English’s polysemy tends to be self-organising through positive feedback. Flickr tags are a great example, which tend to converge on a single agreed term (as seen with recent Hurricane Katrina photos) with time. Newspeak sprung to mind somehow.

SixApart’s Loic le Meur talks proudly about his 8 million users, and then discusses the long tail (also known to us statistician types as a ‘power law tail’). In France, blogs are creeping up this curve into the mainstream, despite predictions that the fad will die. No doubt France’s looser libel laws have helped!

Lunch: Australia 45-0. They look capable of scoring rather a lot more.

My, the BBC are well represented today. Euan Semple takes us through the principle of ‘democratising the workplace’. Euan’s experiences nicely crystallize the differences between types of social software:

Bulletin boards are noisy, quick, not for the faint of heart

Blogs are about personal space, opinion and, more and more, status

Wikis are more formal and collaborative.

Of course, says Euan, any project of this ilk is a leap of faith – not least because of the need to educate managers that the “work/not-work” divide isn’t quite as black and white as it seems. People must be given time to browse, play and experiment.

Our only female speaker is Suw Charman. Suw, although ostensibly talking about ‘Dark blogs’, offers us some valuable rules for getting business blogging. I paraphrase:

Always allow for emergent behaviour - new and unintended use.

Successful projects have a clear business need. If you have this, adoption isn’t the huge stumbling block it's thought to be.

Always look to fit blogs into existing processes. Posting content by email is a nice hacker example. Adapt to your users, don't make them adapt to you.

Avoid scary jargon. No one cares that you're “blogging” – they’re more interested in “here's the link to the page”. Go easy on the paradigm shift prose too – blogging is just a tool that helps you do your job.

Support is more useful than training. People will get the wrong end of the stick; it happens, tread gently with them.

Eat your own dogfood. If you’re not blogging yourself, forget about it.

Getting it right requires reading, thinking, playing, surfing – “invisible work”. If this is frowned upon in your business, you’re wasting your time.

Stop being so anal about RoI, and don't worry about failure.

Afternoon drinks: Two things I thought might happen, have happened. First, Australia are running riot, thumping some really sloppy Flintoff deliveries to the boundaries. Second, the Stormhoek has arrived. And (takes a swig), yes, it's rather nice. I’ll leave the florid wine-lingo description to my ex though.

Julian Bond from Ecademy has some advice for the audience: sell consultancy to FTSE, sell solutions to SMEs. Obviously my interest is in the latter market. Julian explains that there’s definite scope for SMEs to get great use from blogs through a guerrilla marketing strategy: it’s quite easy to become known as an expert in a niche area. There’s a book begging to be written there: “How to be a guru on the web”.

Personal digital identity is Simon Grice’s topic – it’s an interesting one but I’m not convinced it fits that snugly with the conference agenda. Simon talks about mobile devices as being probably the first truly pervasive identity, and the data protection implications of this. As a usual aside, if your mobile phone company pisses you off, ask them for your data under the Data Protection Act. It’ll cost them a lot of time, a lot of paper, and a lot of postage!

Max Neiderhofer’s talk is as lofty and colourful: “What makes blogging fun?” Some interesting demographic information then, for me, the observation of the day:

“Blogging is an MMORPG… the ultimate goal is to be loved and respected.”

How about another? (Max really is good at these soundbites - I’m getting visions of a range of Neiderhofer “Blogging is…” merchandise):

“Blogging is open-sourcing yourself.”

Rules emerge in any game scenario, and for blogging these rules are transparency, honesty and respect. Fail to play by them and you’ll end up being torn to shreds by the hungry blogosphere.

Colin Donald contrasted old and new media in a persuasive manner, by demonstrating the god-awful MTVOverdrive.com (old media at its clueless, broadcast-driven worst) and the small-but-quirky videos.antville.org. The connected age™ is allowing ordinary people to route around mass media, and take control of their own media consumption.

Or so it seems. I wish it was that simple. Unfortunately mass media still has the cease-and-desist firepower to crush all but the most concerted groundswell.

So far, so bloggy. Luckily, Ross Mayfield speaks up for wikis. Pointless aside: wikis are huge in Germany, but not in France. Ross sees wikis as the antidote to email decentralisation. 75% of knowledge assets exist in email. I can see a lot of applications for business support so I’ll put this on the mental ‘to explore’ list.

It’s Friday, the cricket’s still on, we’re starting to flag a little. To round things off, here’s Hugh Macleod (less abrasive than you’d expect from his blog) carrying the now-semi-famous Stormhoek. Hugh covers, with dreadful mic technique, the central thrust of his blog – the death, or at least obsolescence, of advertising. I like the (English) cut of his gib* and I’ll definitely be posting more about his work with Stormhoek.

And that’s it. I need my usual week’s gestation period now to take in some of the concepts - expect follow-ups galore. I think, in the end, that’s all you can hope for from a conference like this – food for thought, and in that respect I think it’s been a great day.

* blog joke, I'm so sorry.