Future Ethics workshop coming to Amsterdam

Since I started offering my new workshop Practical Ethics for Tech Teams, I’ve had quite a few people ask whether I would be holding any public sessions. Good news! In collaboration with The Master Workshop, I’ll be running the workshop in Amsterdam on 20 September (under the title Future Ethics in Technology). Learn about the three lenses of contemporary ethics, use them in lively debates about emerging technology, and apply what you’ve learned through practical, hands-on exercises and games. Early-bird tickets are available now, at a very reasonable €329.

Full details, agenda, and sample slides here: https://www.themasterworkshop.com/cennydd-bowles

Trip to Beer Temple afterwards entirely optional, but recommended. Hope to see you there.

Speculative design’s tricky future

Great piece from Tobias Revell about the wrinkles in the speculative design bedsheets: Five Problems with Speculative Design.

I have a hunch that speculative design is the next big thing, on the brink of being seized and pillaged by the digital design community. Like Tobias I worry that this process will strip away all critical angles. Without criticality, speculative design is just an anodyne horizon-stretching exercise. Vision videos, office workers moving banal UI around glass walls. A mildly useful adjunct to affirmative #ShipIt design, but saying nothing about morality, inequities, etc.

Or perhaps we’ll swing the other way, and churn out rote make-u-think dystopias that deepen designers’ reputations as obstructionists, wolf-criers, and general pains in the collective ass.

Either way, we’d squander the true power of speculative design, which IMO is to engage a diverse public in tough discussions about our futures, and to spread power from technocrats to the people. It’s not about promoting corporate goals or our own pet narratives.

Ethics Should Not Be A Luxury

New article, by me: ‘Ethics Should Not Be A Luxury’: a lament on how ethical products are commonly marketed as luxury goods, and how this hampers genuine, structural change. https://ethical.net/ethical/ethics-should-not-be-a-luxury/

Happy to have this piece published by ethical.net, a London-based non-profit doing the hard work of aggregating ethical alternatives. Think they’re trending on Product Hunt today too. Worth a look.

Evolving Digital Self podcast

For your Friday enjoyment: I was a guest on Heidi Forbes Öste’s Evolving Digital Self podcast, discussing where tech regulation might go next, what happens when global techno-utopian dreams meet nationalistic sentiment, and moving from user-centricity to community-centricity. Listen below or subscribe on iTunes.

New workshop: Practical Ethics for Tech Teams

I talk about ethics with lots of designers, PMs, and tech leaders; they usually say the topic feels important but shapeless. They need practical tips on anticipating harms and unintended consequences, on getting past gut feel to make a compelling case for doing the right thing.

Of course, I think I can help. So I’ve created a new workshop, Practical Ethics for Tech Teams. I ran it for the first time last week with a private client. Here’s what they said:

‘Brilliant. Just so relevant and thought provoking and practical and a masterclass in facilitation. Left feeling very grateful for the work you’ve done, and for making it so accessible to us.’

‘It was BLOODY brilliant! Thank you. Very interesting and engaging.’

‘The exercises, they were all fantastic. Especially the proxemic & mutually destructive [metrics]: so much from them that I can actually apply. Thank you!’

Looks like there’s something valuable here, and I’ve already had lots interest in running the workshop elsewhere. So, if you want to take ethics seriously, my new workshop might be perfect for you. Now booking for in-house clients and as a pre-conference workshop. Includes a copy of Future Ethics for each attendee.

Please share with your networks, and drop me an email at cennydd@cennydd.com to find out more.

Empiricism as anti-ethics

Jack Dorsey and Kara Swisher are having a conversation on Twitter. They’re onto harassment and user safety.

Dare I say, ‘Observe, learn, and improve’ is the ethical problem. Fence-sitting empiricism dominates the industry. Our leaders espouse innovation pace above all, and argue we can mitigate harm after it hurts the vulnerable. It’s a flimsy dodge of ethical responsibility.

Agile and Lean Startup ideologies are central to this, of course. They have convinced us that unintended consequences are unforeseeable consequences, which is untrue. They’ve tempted us to prioritise validation over values. That has to change.

There are methods and techniques we can use to both broaden our view of potential stakeholders and anticipate the ethical issues that may affect them. These methods force us to look up from our familiar UCD and Lean manuals, our experiments, our safety nets. But it’s about time.

My take on chief ethics officers

Kara Swisher’s NYT piece asks whether tech firms should hire chief ethics officers. Some quick thoughts of my own.

I talk about this in Future Ethics; in short, I’m not particularly keen. ‘We need an exec’ tends to be a (slightly facile) default position whenever someone identifies a gap in tech company capabilities. But I think the best approach is rather more interwoven. A chief ethics officer would be too distanced from product and design orgs, where most ethical decisions are made; their duties would come into conflict with those of the CFO, who is already on the hook for financial ethics; and the seniority of the role would mean this person would be seen as an ethical arbiter, an oracle who passes ethical judgment. This is IMO a failure state for ethics. Loading ethical responsibility onto a sole enlightened exec doesn’t scale, and it reduces the chance of genuine ethical discourse within companies by individualising the problem.

Better to appoint senior practitioners – product ethicists, design ethicists – and place them at the apex of decisions, ideally within those respective orgs. Granted, these folks may need someone above to organise, evangelise, and provide air cover. So a chief ethics officer might be useful if hired simultaneously with or just after some IC-level ethical roles. For this to work, this person should be given:

a bit of budget and/or headcount to bring in experts, particularly from academia

serious involvement in (or even responsibility for) updating core company values

some authority, comparable with perhaps a VP; although perhaps not full veto power

flexibility to point outward as well as inward. Tech firms will only succeed at this ethics thing if they share ideas and progress. I’ve just finished a long US tour talking ethics with a range of tech companies (Microsoft, Facebook, Hulu, Dropbox, Fitbit, IBM…): one glaring gap is knowledge sharing and external community-of-practice building, which would make progress quicker and smoother. I have some vague thoughts about how we might address this; more later.

A successful chief ethics officer would equip teams to make their own decisions, not bestow judgment from above. The best approach is a mix of theory, process, and technique to (per Cameron Tonkinwise) make ethics an ethos, not just a figurehead appointment.

Future Ethics out now

In Ho Chi Minh City I met a man who claimed, implausibly, to be a wizard. Dumbfounded by jetlag and, regrettably, the entire contents of the minibar, I followed him down a dusty side road. It split at an old tree, whose dead branches caressed the horizon. ‘Here’ he said. ‘Choose.’ I followed the path to the left; eventually I happened upon a bottle, encrusted with dust. Within it, a brittle, rolled-up piece of paper, scorched at the edges like a piratical treasure map. What else could I do? I unfurled it.

‘Don’t write a blog when you’re trying to write a book.’

Anyway, Future Ethics is out at last, and more of this nonsense will follow. I’m en route to Seattle; from there, the west coast, top to bottom. Microsoft, Dropbox, Stanford, Facebook, Hulu, EY, Intuit, Kluge, and a few public events too. I’ll be talking about the book a lot, but you bet your ass I’m going up the Space Needle and taking Hollywood sign selfies too. Expect photos.

Please buy my book, in the interim. I’m proud of it, and so far, people seem to like it.

A techie’s rough guide to GDPR

[This was originally written for my upcoming book Future Ethics, but might be too boring to make the final draft. I must stress this post does not constitute legal advice; anyone who takes my word over that of a properly qualified lawyer deserves what they get. I recommend reading this post alongside the UK’s ICO guidance and/or articles from specialists such as Heather Burns.]

A large global change in data protection law is about to hit the tech industry, thanks to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR). GDPR affects any company, wherever they are in the world, that handles data about European citizens. It becomes law on 25 May 2018, and as such includes UK citizens, since it precedes Brexit. It’s no surprise the EU has chosen to tighten the data protection belt: Europe has long opposed the tech industry’s expansionist tendencies, particularly through antitrust suits, and is perhaps the only regulatory body with the inclination and power to challenge Silicon Valley in the coming years.

Technologists seeking to comply with GDPR should get cosy with their legal teams, rather than take advice from this entirely unqualified author. However, it’s worth knowing about the GDPR’s provisions, since they address many important data ethics issues and have considerable implications for tech companies.

GDPR defines personal data as anything that can be used to directly or indirectly identify an individual, including name, photo, email, bank details, social network posts, DNA, IP addresses, cookies, and location data. Pseudonymised data may also count, if it’s only weakly de-identified and still traceable to an individual. Under GDPR, personal data can only be collected and processed for ‘specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes’. The relevant EU Working Party is clear on this limitation:

‘A purpose that is vague or general, such as for instance ‘Improving users’ experience’, ‘marketing purposes’, or ‘future research’ will – without further detail – usually not meet the criteria of being ‘specific’.’ —Article 29 Working Party, Opinion 03/2013 on purpose limitation, 2 April 2013.

So, no more harvesting data for unplanned analytics, future experimentation, or unspecified research. Teams must have specific uses for specific data.

The regulations also raise the bar on consent. User consent is required unless you can claim another lawful basis for handling personal data. One such basis is ‘legitimate interests’, but this isn’t the catch-all saviour it may appear. To take this route you need to demonstrate your interests aren’t outweighed by others’ – it’s likely this only applies where there’s minimal privacy impact and no one could reasonably object to their data being handled in this way.

Where requested, consent must be freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous – and indicated by a clear affirmative action. These few words form a death sentence for data dark patterns. Pre-ticked and opt-out boxes are explicitly banned: “Silence, pre-ticked boxes or inactivity should not therefore constitute consent” (Recital 32, GDPR). ‘No’ must become your data default. Requests for consent can’t be buried in Terms and Conditions – they must be separated and use clear, plain language. Requests must be granular, asking for separate consent for separate types of processing. Blanket consent is not allowed. Consent must be easy to withdraw; indeed ‘it must be as easy to withdraw consent as it is to give it’. No more retention scams that allow online signups but demand users phone a call centre to delete their accounts. Finally, parental consent is required to process children’s data – the age at which this applies is down to individual EU countries, but can’t be lower than thirteen.

GDPR also defines some riskier data as sensitive: data on race, ethnic origin, politics, religion, trade union membership, genetics, biometrics used for ID, health, sex life, and sexual orientation. This ‘special category data’ always requires explicit consent. As often happens with new legislation, it’s not yet clear exactly what this means and how it differs from standard consent, but technologists should nevertheless tread carefully.

GDPR also offers eight individual data rights. Some are straightforward. EU citizens have the right to rectify false information and to restrict certain types of data processing. They have the right to be informed about data processing, usually through a clear and concise privacy policy that explains nature and purpose. They have the right to access their personal data held by companies. This must be sent electronically if requested, within a month of the request being made, and must be provided free unless the requests are repetitive and excessive. (Building a self-serve system for access requests might be a smart move in the long run.) Individuals also have the right to object to data processing. If the data is being used for direct marketing, this objection rules all: you cannot refuse to take someone off the direct marketing list.

The three remaining individual rights are more complex and ethically interesting, and deserve closer attention. First, GDPR provides a right to data portability. Not only can users request their data, but it must be provided in a structured, machine-readable format like CSV, so users can use it for other purposes. However, this isn’t an own-your-data nirvana – it only covers data the user has directly provided, and excludes data bought from third parties or new data derived through, for example, segmentation and profiling. Businesses that choose the ‘legitimate interest’ justification for data processing (see above) are also exempt. However, this new right still threatens some comfortable walled-garden models. For example, social networks, exercise-tracking apps, and photo services will have to allow users to export their posts, rides, and photos in a common format. Smart competitors will build upload tools that recognise these formats; GDPR might therefore help to bridge the strategic moats of incumbents.

Users also have a right to erasure, sometimes known as the right to be forgotten. This has already become a cause célèbre for data rights, and legal cases are swirling around the topic. It’s important to note there is no absolute right to be forgotten under GDPR; the right only applies in specific circumstances, and requests can be refused on grounds of freedom of expression, legal necessity, and public interest. The ethics of forgetting are fascinating and way beyond this post; I’ll save that for the book. But in The Ethics of Invention, Sheila Janasoff argues convincingly that this right helps to constitute what it means to be ‘a moving, changing, traceable, and opinionated data subject’. It’s a particularly important right for children, although it also has the potential to be abused by those trying to hide wrongs. And a right to be forgotten may come into direct conflict with emerging technologies: good luck handling a right to erasure request if you’ve already committed the data to an irrevocable blockchain.

The eighth individual right relates to automated decision making and profiling. This has sometimes been misrepresented as a right to explanation; i.e. that companies must explain on demand the calculations of any algorithm that takes decisions about people. This right doesn’t exist within GDPR, although it may need to exist in future. (Again, the ethical angles of explainable algorithms are complex and need to be covered separately.) GDPR’s automated decision right requires companies to tell individuals about the processing (what data is used, why it’s used, what effects it might have), to allow people to challenge automated decisions and request human intervention, and to carry out regular checks that systems are working properly. This last phrase is promising: regular auditing of decision-making systems will hopefully mean algorithmic bias will be exposed and eliminated sooner.

GDPR makes a special case of fully automated decisions that have ‘legal or similarly significant effects’, giving examples such as algorithms that affect legal rights, financial credit, or employment. These can only be undertaken where contractually necessary, authorised by law, or when the user gives explicit consent. In these high-risk cases, individuals have a right to know about the logic involved in the decision-making process. It seems likely that an outline of how the algorithm works might suffice, rather than providing the data relating to this specific decision. Companies must conduct an impact assessment to examine potential risks, and take steps to prevent errors and bias.

GDPR’s other highlights include an obligation for teams to practice data protection by design and tight stipulations to notify authorities about data breaches. And, for the first time, it’s all backed up by meaty penalties: up to 4% of global turnover or €20 million for the most severe violations.

Complying with GDPR will require tricky changes to algorithmic design, product management and design processes, user interfaces, user-facing policies, and data recording standards. You’ll have to spend time designing consent-gathering components, unless you can claim a justification that obviates consent. You may end up with less rich customer insights than you had before. Some KPIs may slump. But for companies that have direct customer relationships, it’s all manageable, and on the upside you not only reduce your compliance risk but benefit from the increased trust your customers will show in you and the online world in general.

However, there are a small number of companies who should be very worried. GDPR will expose the tracking that is now commonplace on the web, and it’s fair to expect widespread revolt. Without a direct customer relationship, third-party ad brokers and networks must rely on publishers to gather consent; but no publisher will willingly destroy their user experience with dozens of popups for their ad partners (remember: consent must be granular!). Even if a publisher did volunteer for this self-mutilation, expect users to universally refuse permission for their data to be used for tracking. It’s highly doubtful the ‘legitimate interests’ excuse will work for ad networks either; the balance-of-interests test is unlikely to go their way. The black box will be forced open, and people will find it’s full of snakes. Dr. Johnny Ryan of PageFair puts it bluntly: GDPR will ‘[rip] the digital ecosystem apart’. Expect panicked consolidation in adtech as networks realise they can’t simply sit in the middle; they must somehow own the customer relationship to control consent. It’s likely adtech firms may even try to acquire publishers for this reason. And it’s likely some will die. No flowers.

[Photo by Curtis MacNewton on Unsplash.]

The weirding of design: thoughts on #AIRetreat

I’m on an anticonvergence swing. The rush to systematise, to codify, the release of yet another manifesto or code of ethics – it all tires me out. These attempts feel premature at best; at worst they feel like vehicles for status and positioning, not genuine impact.

I was worried #AIRetreat would trace a similarly prescriptive path, and I arrived ready to play the role of candid saboteur. Two and a half days isn’t enough for twenty people to reach consensus on something as complex as artificial intelligence. Instead of a doomed attempt to plot an accurate map, I wanted us to tell stories of our respective hometowns, the origins of our myths. I wanted to hear which hills smoulder with the smoke of dragons.

Many of the attendees were wrestling with professional difficulties and neuroses. Existential quandries hung in the air. I know well that events like this risk looking elitist, self-congratulatory – but believe me, there was vulnerability. Souls were bared.

AI is overwhelming in scale. At times I feel like the triangle player in the orchestra – can I really add anything worthwhile? So we talked about giving ourselves the conviction to contribute but the grace to step back. We threw around our pet ideas to weigh them, to examine their shape, to see how they bounce.

The old designer hammer-nail combo raised its head at times: Post-Its flew onto the windows, and we couldn't help but categorise. Perhaps more interdisciplinarity would have helped. But of course designers do have something to add to the AI conversation; some human-leaning balance to a field colonised by the technical. And that conversation was fast and deeply intelligent. After some early toe-dipping of theory and labels, we leapt in – sex, ethics, consciousness, existential risks, mundane dystopias. We agreed on the folly of separating technology from its social context – augmented reality, for example, makes this fallacy blindingly clear – and argued whether AI should amplify or alter humanity.

It’s important the public has a say in AI discourse, lest we slip into technocracy. But the cultural tropes of AI don’t help. We need to go past the Terminator/HAL angle, the white plastic humanoid handshake motherfuckers. We need new art, new metaphors, new visual and narrative motifs for AI. Black Mirror does a great job in its millennial-Aesop way, but designers and artists have valuable skills that could further provoke the conversation. Can we, for instance, create compelling visions of not the black mirror but the magic window? Can we sketch out a technology that points outward, exploding the hidden components of our environments and lives, collapsing the distances of capitalism (provenance, labour, energy) and helping people make more informed choices?

In this territory, art movements and speculative prototypes surpass manifestos. I think if we’re to really contribute to the territory of AI, we need weirder design practices. We can’t think of interfaces as deterministic, nor interactions as linear. Designers will have to expand both their inputs and outputs: fiction, posters, plays, and games could play roles as large as products and blueprints. I see more value in the futures toolbox than the usability test.

I have to mention the nature. We met at Juvet, famous from Ex Machina, buried in the mountains of northern Norway. The air was crisp and the changing autumn light threw time out of balance. Kairos ruled and chronos melted away. Yellow and ochre leaves tumbled into the river. We marvelled at the Milky Way and the (faint but undeniable) Borealis. We climbed a great big hill, gulping cold air and pointing at the glacier beyond. Once we descended, we drove just a little further, to Trollstigen. As we rounded the bend, we realised the sheer size of the valley ahead, and it took our breath away.

The bored designer’s reading list

At some point in their career, every digital designer gets tired of the typical didactic tech literature. So many tools, so many techniques, so much heat – yet so few ideas. Lately I’ve been fortunate to read some fascinating books that loosely orbit my design and technology interests. Most bias toward theory rather than practice. They’ve helped sharpen and reinvigorate me; perhaps they might work for you too. I’ve included a couple of suggestions from Twitter – thanks to everyone who contributed; please forgive curatorial omissions. See replies to my original tweet for more.

Disclosure: I’ve put referrer links on these. I’m currently playing the role of low-income writer myself, and I’m not too proud to try to cover some of my unabating research costs.

Datafication and ideological blindness

“Our bodies break / And the blood just spills and spills / And here we sit debating math.”

—Retribution Gospel Choir, Breaker

Design got its seat at the table, which is good because we can shut up about it now. What used to be seen as the territory of bespectacled Scandinavians is now a matter of HBR covers, consumer clamour, and 12-figure market caps. People in suits now talk about design as a way to differentiate products and unlock new markets.

The table is a metaphor for influence, of course. Designers already have plenty of tactical influence – interface, layout, structure and all that – but this is influence of a different order. It is deep and internal: influence over culture, vision, and most of all strategy, the art of deciding where to go and how to get there.

In this realm, data is king. Whether from device sensors, social media chatter, or experiment analytics, data pours off every surface of the modern world, and people are happy to sell us expensive tools to analyse it.

Data has transformed strategy across many industries. Sports fans and insiders alike have become trainspotters: the minutiae of Moneyball, of take-on percentages and suspension loads are now mundane. Evidence-based medicine has put empiricism at the heart of the profession, with randomised controlled trials guiding new treatments and in some cases reducing mortality.

But outcomes are only half the story. Much of the appeal of this datafication is ideological.

“Quantified thinking is the dominant ideology of contemporary life: not just in scientific and computational domains but in government policy, social relations and individual identity.”

—James Bridle, What’s Wrong with Big Data?

The tech industry believes itself to be neutral and objective. This is pure self-delusion. Ideology runs hot through the veins of the sector. So blown are we by the winds of the New, it takes just weeks for a prevailing zephyr to align all ships in the same direction.

Today’s dominant tech ideology is Lean Startup, a California-ised nephew of Lean Manufacturing. The family resemblance comes in the elimination of wasteful work that fails to meet customer needs. So far, so obvious. In practice Lean Startup almost exclusively manifests as accelerated empiricism.

Lean Startup’s central tenet is that we’re surrounded by unparalleled uncertainty, to the extent that accurate forecasting is impossible. Therefore, adherents claim, the only worthwhile way to build is through stepwise iteration, in a perpetual cycle of Build-Measure-Learn. The notions of intuition and prediction are negated, deprecated by data.

I’m not convinced by the presumption. Certainly the tech industry operates amid flux, but the wide-angle view of this change is more predictable than many would admit. Bill Buxton famously claimed consumer tech has a 30-year ramp-up, pointing to the mouse and the touchscreen, first prototyped in R&D circles in the mid-1960s. Even the Gartner Hype Cycle, tacky as it is, offers a plausible model of trajectory and velocity for emerging technology. With intelligent extrapolation and study, the next five years of technology is hardly a mystery. The second-order and social impacts are murkier, true, but here a spot of science fiction scrutiny and primary research surely isn’t beyond us.

But the message is out of vogue, and a posteriori empiricism is in the ascendancy. So datafication it is, and with a narrow view of data at that. In Lean Startup as now practised, data is first and foremost quantitative, usually gained from user analytics and multivariate experiments.

I’ve studied a good deal of mathematics and statistics, and know the power of quant data. But I also know its limitations, and have seen first-hand the dangers of data ideologies excluding other decision-making inputs.

Scenario 1 – experimentation trumps coherence

I’ve worked with two companies where the primary product strategy has been reducible to “Increase this KPI”. The same sorry tale has panned out in both.

At the start, things look positive. Per executive edict, employees concoct product experiments to move the needle. Pace of execution goes up, pet projects ship, and people are pleased at the rapid throughput and product change. Sometimes the measure does indeed move, and from a distance it certainly looks like innovation.

But almost all these experiments are additive, so the interface gets crammed. White space is eroded by buttons and info. Successful A/B trials ship to 100% regardless of coherence and intent. The product slowly becomes cluttered and the value proposition becomes incoherent. Secondary metrics that lie outside the scope of the experiments, such as retention or NPS, start to plateau, then slip.

Worse, the internal framing of users shifts. Employees start to see their users not as raison d’être but as subjects, as means to hit targets. People become masses, and in the vacuum of values and vision, unethical design is the natural result. Anything that moves the needle is fair game: no one is willing to argue with data.

PMs and engineers decide that since they can ship pretty much whatever they like, they bypass what they see as designers’ obstructive, oversensitive tendencies. Deployment authority becomes the ultimate power, design morale plummets, and designers quit. This proves to be a leading indicator of company morale, and general confidence in leadership sags shortly after. Failure to provide a strategic North Star is itself an absence of leadership; a timid disavowal of responsibility for direction. So the short-term happiness soon fades, and the breakdown of collaboration and strategic coherence proves hard to reverse. Usually you have to sack an exec or two.

Scenario 2 – Safety dominates

In a data-paralysed company, conviction is discouraged. Skills are diminished to perspectives, and only hypotheses have currency: weak opinions, barely held. There’s a shift from fulfilling user need to squashing risk, and heavy conservatism sets in. The symphony orchestra of design is reduced to the barbershop quartet of conversion rate optimisation, and the product hillclimbs to the well-known local maximum. Innovation becomes purely incremental.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with incremental innovation per se, unless it becomes the only way you innovate. In an environment of data-enforced caution, there’s no way to climb down that hill to higher pastures elsewhere: a single metre is downhill, so you’ll never walk a hundred. Companies thus paralysed, unable to take bold steps in new directions, become vulnerable to eventual disruption.

This malaise is particularly dangerous because it’s symptomless until too late. Your outlook seems healthy for many years until one day you’re suddenly irrelevant.

For most companies, deep commitment to product/market fit will prove more valuable than a safety-first optimisation mindset. As Ben McRedmond of Intercom says, a billion-dollar business was never built off better button colours. At vast scale, a 0.1% conversion uplift could indeed mean $millions, but to a company not in that league, premature datafication could be fatal. Better to focus on truly understanding and addressing user needs rather than shaving a tiny advantage in a conversion funnel. Optimisation is the cherry, not the cake.

Scenario 3 – copycat strategies

Replacing strategy with metric optimisation is stupid enough, but it’s even more dangerous for companies that choose the same metric as competitors.

Social networks typically make engagement their primary target, and consider it a proxy for user success. It’s now clear that among the strongest drivers of social network engagement are rich media (images and video), contemporaneity, and easy feedback mechanisms. Little wonder then that all social networks are headed toward the same territory of videos, live streaming, and push-button social grooming. It’s the preordained endgame of a battle for engagement, and so every social network starts to look the same.

A strategy is useless if your stronger competitor has the same strategy. Without differentiation there’s no advantage, so metric-copycat strategies tend to lead to one of two scenarios:

If scale matters (any domain with Metcalfian dynamics, e.g. multiplayer gaming, social networks, two-sided platforms like classifieds or ride sharing), the winner takes all. Any incumbent would love its competition to ride the same rails – it can then leave the risky R&D/innovation to the chasing pack, cherry-pick what works, and roll it out to a wider audience, thus protecting future market share. Why bother checking out the alternatives when we’ve copied the best bits here? Call it a fast-follow strategy if you want to wrap its ethical deficiencies in a cloak of respectability.

If network effects are negligible (e-commerce, publishing, task-based software), cost is the only real differentiator left, and it’s an ugly race to the bottom. Again the bigger player usually wins. They can discount the sharpest and absorb losses the longest, then ramp margins back up once the competition is dead.

Scenario 4 – flawed data, flawed decisions

If you’re putting data at the heart of your decision-making, you need to get it right. That means:

employing skilled staff who will set up experiments accurately, avoid flaws such as p-hacking, and have the numeracy and statistical capability to draw valid insight from your raw data.

investing in watertight analytics technology with excellent uptime and security.

a laser-like focus on team efficiency and deployment. No point garnering insights if you can’t act.

surprisingly large sample sizes. Thanks to the complexities of statistical power, you may find a minor tweak in a low-conversion process will need a >100,000-user sample for a valid test.

Without these, you may be making decisions off faulty data. Worse, you won’t even know. Thanks to the legitimising effect of datafication, you’ll feel highly confident while doing the wrong thing; betting on a hand of four ♠s and a ♣ that you misread as a flush.

Data can of course be an enormously valuable strategic input, if these pitfalls are sidestepped. Senior designers and leaders can’t withdraw from the data discourse, but they are well placed to question its ideological power. Data is a valuable adviser but a tyrannical master, and in some companies datafication has such a stranglehold that other approaches are permanently in shadow.

Fortunately, these companies are easy to spot: they call themselves “data-driven”. Run from data-driven companies. In thrall to semi-science and blinded by their dogma, they’ve lost the ability to see intelligent alternative perspectives on their business, their products, and the world. Embrace instead data-informed companies. This isn’t mere grammatical pedantry – a company genuinely informed by data understands the risks of datafication and adopts sophisticated, balanced approaches to strategy that blend quant, qual, and even some of that unfashionable prediction and intuition.

What design sprints are good for

You likely know the design sprint format already, thanks to the GVers’ evangelism: a five-day greatest-hits tour taking in collaborative ideation, sketching, prototyping, and user testing. Heavy timeboxing and lots of dot voting. It’s an intensive but effective format and, to those who don’t realise constraints force creativity, it’s surprisingly versatile.

Design sprints offer an apparently straightforward value proposition: get from idea to insight while skipping build and launch. High impact, risk reduction, learning at minimal cost – all perfectly aligned with current lean trends.

Sprints appeal to design consultants too. They offer clean engagement edges and require a complex skill mix – facilitation, strategy, prototyping, training – that commands high rates and opens the door to follow-on work. I love them, and they’re now the bulk of my consulting.

But I’ve done enough sprints to know the real value isn’t always as advertised. Clients naturally want to twist them for their own needs, to wring even more juice out of the process, despite the rigid structure. And that’s fine, because sprints are good at some unexpected things, and bad at some unexpected things too.

Design sprints are good for…

Generating momentum. Particularly in larger companies, design and innovation can appear sluggish, but a single week-long sprint lets you temporarily hush whispers of vapourware and show something – real pixels! – that represents at least a decent first thought. This makes sprints particularly valuable for new teams or leaders who want to hit the ground running. It can also galvanise teams to move quickly, setting examples of cadence and establishing a norm of getting assumptions out of heads and into product explorations. The next challenge is to maintain momentum while fending off overexcited expectations.

Highlighting the scope of the design process. Particularly for stakeholders who see design as all downstream aesthetics, a sprint demonstrates that design decisions run all the way through a product, like mould in a good cheese. Your sprint will show the value of broad input from outside PM and Design. Engineers, writers, and support staff should at least feature in Monday’s ask-the-experts interviews; better yet, they should wield pens on Tuesday and Wednesday. If your sprint goes really well, your client will spiral into existential crisis about the difference between design and product management, and you’ll know you've earned your money.

Developing the team. Best to split up prototyping duties rather than pile them all on the designer’s shoulders. So you’ll need to teach some Keynote prototyping: just enough that your teammates will add it as a skill on LinkedIn. You’ll also quickly discover when you don’t have the right people or skills in the room. Perhaps visual design becomes a bottleneck, no one wants to commit to copywriting, or the real decision-maker isn’t available: these problems won’t go away unless you address them.

Provoking core product issues. The interesting questions about a product sometimes only surface once you start designing. A design sprint is an exploratory drill for complexity – you may discover vast reservoirs of viscous complications, or your gushing wells may suddenly dry up. This is where an experienced team helps: red flags and here-be-dragons hunches are useful signals. By the end of the week, you may all be convinced the project doesn’t have legs. Usually no one will say so on the spot, so as not to repudiate a tough week, but if the week’s primary outcome is to shitcan the project, that’s great. It only took you a few £000 rather than a few £000,000.

Design sprints aren’t good for…

Reliable product design. Sorry. Even though you have to select tight boundaries for your prototype, you’re still going way too fast for considered design. Sketching, writing, and prototyping 10–20 pages (you’ll end up with this number, even if you try to do just four) in a day or two is a dangerous pace. Even the most experienced designer will find her sketches don’t always translate to the screen – in-tool juggling and shuffling is a natural part of the design process, and from my experience deserves a minimum of ½ day per page. The sprint offers no time for design critique and no time for polish. Nothing I’ve done in a design sprint is portfolio-ready. And that’s entirely the point. A sprint is the opening gambit of a long, complex game – a tool of provocation, not delivery.

Proposing sophisticated user research. Design sprints reflect the learn-through-making ideology that dominates tech culture today – hence Friday’s user tests. But the week does little to suggest opportunities for deeper research such as ethnography, longitudinal learning, ethical inquiry. Instead, a sprint suggests more of itself: more making, more testing, more iteration. If you’re not doing any user research that’s a decent start – you’ll at least learn some fundamental test facilitation skills, although probably not so much the synthesis and analysis, which contain the real flavour and demand practice. But beware the limitations of user tests. The design sprint doesn’t really shine a light on more sophisticated research methods, and nor is it meant to. Hire a researcher.

Answering deep product-market fit questions. A sprint will absolutely provoke these questions, and then leave you dangling. Remember this is a design sprint, not a product sprint. Don’t expect to learn much about market sizing or segmentation, customers’ propensity to pay, business model viability, or your propositional appeal against competitors. There are better tools for that. You can try to get some answers in the tests, sure, but it’s all hypotheticals all the way down – "would you pay for this?" – which are subject to all sorts of bias and divorced from true behaviour. Proper market research this is not.

Getting the green light. The only acceptable approval decision after a design sprint alone is “Let’s not do this project”. Unless the project is cheap and very low-risk (in which case, you wasted a week anyway), a design sprint won’t give you enough reliable information to approve a project. Address the previous paragraph first.

Some bonus tips because why not

Prototype in high fidelity. As high as you can. Real text, real images, believable visual direction, colours, type. I’m less and less convinced by low-fidelity testing: the mental gap is just too large. And why would you pass up the chance to learn about people’s responses to brand, to copy, to aesthetics?

Keynote doesn't handle scrolling well, so add a fake scrollbar for desktop-and-mouse-based prototypes. Keep it simple. It’s tempting to add a thumb (that’s the bar in the middle of the scroll track), but users will try to drag it. Up and down arrows are fine.

Amend your Keynote toolbars. Put Group/Ungroup, Front/Back/Forward/Backward, Copy/Paste Style, Mask, and Lock/Unlock in there. Like this. You'll use them a lot.

Use Keynude to override Keynote’s woeful default shape properties. For some reason I’ve found it makes some of the Keynote UI appear in French. Learn French if this is a problem.

Have a writer in the room.

In-house tests are better, but you can export your Keynote to HTML, throw it on a server, and run passable remote tests via Skype etc.

Open your test with a blank Google page / App Store / whatever page and ask users how they’d search for your product. This helps you learn about their language and existing mental models. Show them a dummy results page that links to your prototype, and away you go.

If you liked this and want someone to run a design sprint at your company, I offer a six-day consultancy package – ½ day set up, 5 days onsite (anywhere in the world, subject to visa bits), and ½ day for review, wrap-up, and next steps. Contact me to find out more.

2016 in review

It’s early for this sort of thing, but time has collapsed.

I played at being a one-percenter in 2016. I can see the appeal. I swam in rooftop pools and people called me “sir”. I waved my Platinum Ambassador card and drank champagne in airport lounges. I learned an important part of playing rich is smiling and saying thank you with plausible sincerity.

Turns out I haven’t the sustainable income or the shamelessness the lifestyle requires. A year of pampering will suffice. But I’m keeping the sport: Le Mans, Centre Court, Wrigley Field, Lord’s. Still something moving about the sacrifice, something (in DFW’s words) about athletes’ ability to “carve out exemptions from physical laws”. Wales at the Euros was beyond imagining, all heart-bursting hiraeth and boundless gratitude.

I got into cycling because it’s what thirty-something men do in my city. I worked on a few challenging projects and spent many days deep in the British Library, researching the book. I can now talk convincingly about Kantian ethics and non-human forms of agency.

My favourite album was Pantha du Prince’s The Triad. The USA elected a neofascist.

2016 – we must will it behind us, even now – was unique in its dread, so determined was its self-infliction. We wielded the razor brave and true down our own wrists. How do I reconcile the guilt of the best year of my life against a backdrop of such distress?

Perhaps it’s easiest to wallow in dystopias, because those war game scenarios, aren’t they just irresistible? Choose your own apocalypse: Putin rolls into the Baltics / Erdoğan goes full totalitarian / North Korea finally gets their physics right – whatever the route, the endgame is the same. Per Tobias Stone’s speculation, flags are hoisted, DEFCONs plummet, and people like us topple into mass graves, our Kantian ethics useless. Long-term calamity is of course assured too, now climate deniers run the world. But the long term no longer seems to matter; the future has become an anachronism.

And this is what we voted for.

Come on, they say, this is a laughable overreaction to protest politics. But I’ve read Orwell, man, I have an Economist subscription, I am the problem. We all die, but I was right, I was right, if only you’d listened…

Enough self-indulgence. Nihilism is a luxury only the privileged can afford. But the other immediately promising strategy – desperate hedonism, live for now before the New Dark Ages set in – well, I’ve rather played that out this year.

Which leaves… I don’t know what. I’m too old and cowardly for the Black Bloc antifa shit, but being careful with pronouns, reassuring people they’re welcome: it’s noble and generous, sure, but it does nothing to change this momentum. There must be other strategies, more ways to fight what today seems bleakly inevitable. I hope I find out what those are in 2017.

Blind spot

Goddamn AC in here’s like a child’s breath. First meetings are tough enough without getting this sweat on, and we’re still waiting on that refurb thanks to Homeland jumping the line. I still remember the grumbling in DOT when Homeland got their increase. You’ve never seen a pretzel line so long.

“Thank you all for being part of this historic ethics delegation. As you know, the Safer Cars on American Roads program has been active since January in Washington, Pennsylvania, and California. I think we can say that, minor bumps aside, it’s gone well at the state level.” A few Pittsburgh taxi drivers had thrown themselves under the Uber XC90s, but they’d earned only scant sympathy and six-figure medical bills.

“Before we progress to federal and NHTSA approval Meg has asked us to dialog the outstanding ethical questions. So that’s the role of this group.” Important at meetings like this to be metronomic with eye contact, to feign impartiality. There’s protocol, recordings. “Since we have a few newcomers, let’s start with brief introductions. Brief, please.”

I point my pen at the kid I’ve not met, who must be Eric. Twenty-five, six? He leans back in his chair. “I’m Eric Jo. I’m a staff engineer at Alphabet.” He means software engineer, of course – car people don’t wear those ridiculous watches. His t-shirt has ‘Google SDCP’ printed above that laughable cute fascia. Eric wears the resigned look of a young man left holding the short straw, glasses about five degrees off horizontal.

Next to Eric, Bud Carver, in his yellow Wednesday suspenders. Bud’s a professional fucking saboteur. Spends his days hovering in departmental meetings, complaining the meeting shouldn’t happen. I’ve protested to Meg of course, but the guy’s inner circle: some kind of Tea Party figure before Don threw him the DOT trimmer gig.

Been perhaps three years since I last saw Cecilia – she was at Mercedes forever, then went totally quiet. Like, nothing. Vanished from the mailing lists, wasn’t at the Denver convention, then we finally got word from Cupertino two months ago. Great engineer. We still don’t really know what they’re up to over there: all sorts of stories of cutbacks and prototypes. Not exactly a forthcoming bunch.

Of course, Facebook sent Roosevelt. Ever since the Post alleged their latest prototype brakes more heavily in front of Democrats, Legal stepped in. I tried to discourage lawyers – this is a working group after all – but it’s hard to change Facebook’s mind these days.

Dylan and I go way back. ASU, class of ’96. There were rumors Kalanick himself wanted in on the committee until Uber PR nixed the idea. Dylan wiped the floor with me at Spyglass last month: went round in 77 and won’t let me forget it. He emailed last week to announce his new title – “Director of Strategic Infrastructural Programs Direction” – and asking “to powwow about subsidy opportunities” before the next spending reviews.

“I’m Alexandrine Lang, I head up future projects at VW Group.” Three weeks back, an Audi A6 suddenly occupied Meg’s parking space, GM-Ford were out, and Alexandrine was on the list. The PR optics aren’t good since we let VW wriggle off the emissions hook, but at least they’re eager to please.

Finally, Floren Moïse. Heard he was the only Georgia Tech guy to decline the UPS offer. Meg’d be happy to ditch him, but Floren adds spice: specifically, he drives Bud crazy. I don’t know how exchange programs work in that world, but Atlanta has eroded his accent somewhat. He’s wearing one of those collarless shirts, buttoned to the top. A dapper academic: who’d have thought?

“Thanks everyone. Jaxson sends his apologies – as you know, the Autopilot hearings are ongoing and delicate, so we agreed Tesla should step back for now.”

The coffee pot spits in the corner. A fern wilts silently in the heat.

“Our first order of business is federal border protocol. Our friends at Justice tell me you’ve all implemented their patrol-car stop recommendations; they pass on their thanks. We now have to consider how to handle international crossings.

“Per last week’s memo, Homeland has requested not only the checkpoint dead-zone but remote shutdown capability within a 3-mile radius. This would mostly be an issue on the Canadian border, of course, but while California’s dragging its heels over the Wall, it may be relevant in the south too.”

“Three miles is going to be risky," says Eric. "From an engineering point of view of course there’s no obstacle, but at that range I don’t think we can guarantee safe shutdown in mixed-autonomy traffic, unless we have the specialized lane filters.”

Cecilia speaks precisely over steepled hands. “Our view is that a remote disable sets a worrying precedent. A backdoor is a euphemism for a vulnerability, after all.” She hesitates. “I must add however that Apple has no official stance on autonomous vehicle behavior, and I am unable to confirm or deny my presence at this delegation.”

“Look, the Russians are basically all over our asses at this point, Tom,” says Dylan. “Putin’s got a gifted crew behind him now, and if we give Homeland a backdoor it’s just a matter of time until the Russians jack-knife a semi on I-5. Christ, Tom, it’ll be a mess. Uber… they don’t want to put passenger lives in danger.”

“But the true problem,” interrupts Floren, “is we would be subverting the established capitalist model of ownership, we reframe the relations of subject-object. Are we morally justified in imposing this ludicrous proto-authoritarianism on the world?”

It’s usually harmless to let Floren lap the course a few times, to let him exercise those post-nominals and flap about us focusing on the wrong horizon. By the time he’s expounded upon the distinction between deontology and consequentialism, Bud’s eyelids are twitching.

“Let’s get back on track, folks,” I say. “Frankly, I’m not worried about a little top-down control. Our focus groups tell us that, except for the usual ACLU types, citizens are comfortable with authority intervention, so long as it’s framed as a safety measure. But let’s cut the crap – we all know the deal with the remote shutdown. You just want deniability in case another Snowden crawls out.”

“Well, silence that made whole scenario far more painful than it needed to be,” says Roosevelt. “If DOJ actually allowed us to disclose interventions I’m sure we’d all be warmer to the idea. This is basic First Amendment stuff, Tom, and as you know we’ve been over it a thousand times with any department that will listen. And since the FBI disclosure cases are still in this mysterious holding pattern, we don’t seem to be getting anywhere.”

“Yeah, okay, look – it’s between you and Homeland really. We’re just the messenger on this one,” I say.

“I think the moral angle has to be secondary to the legal case. If Homeland makes a formal request we’ll consider it through the proper channels. Until then, it’s a no.”

Bud, already on his third cookie, is staring at Alexandrine. A small column of saliva pulses between his open lips. She shifts awkwardly in her seat.

“Fine,” I say, “I’ll circle back with Homeland’s counsel. They seemed eager, so my guess is this’ll come back. Anyway, since we’re on legal turf, let’s move into collision liability.” Bud shuffles his papers; everyone else swipes their tablet. “Per the April ISO draft, vendors will assume liability in level four-compliant autonomous modes. So we still have to thrash out what we’re doing about laggard firmware. Uh, Dylan, can you update us on Uber’s stance here?”

“Sure,” Dylan says. “They’re now prepared to disable vehicles once they’re 30 days behind the upgrade curve. But as you know, inventory is Uber’s priority – vehicles out of service really hurt their passenger load factor. So for lesser lags the passenger will see a HUD warning, and if they dismiss it, liability shifts to the passenger or his insurer per EULA.”

“Okay, thanks. Alexandrine, since VW is new to the group, can you fill us in on their thoughts?”

“We’ve carried out surveys to crowdsource our collision heuristics, which we expect to underpin all software versions. So patching shouldn’t be an issue. Actually, the surveys have been very illuminating. They’re based on something called the trolley problem – have you all heard of it?”

An exasperated crunch escapes from Floren’s throat, and Cecilia and I exchange a glance. Eric takes pity first. “Look… the trolley problem is basically useless in real life. If you find yourself crashing it’s because you fucked up three seconds earlier, and the answer is almost always just to smash the brakes. Steering makes you lose more control, and a few mph might make all the difference.”

“Gotta say I’m with Eric here, Alexa,” says Dylan.

“Alexandrine.”

“Oh – Alexandra, sure. Sounds like you should lean on your machine learning guys more. Predictive heuristics are a waste of time. Ship with an adaptive ML system, learn from fleet damage, injury records, y’know? Let the algorithm choose a response based on previous patterns.”

“Nom de bleu,” cries Floren. “You tech people are like this always. Such wretched solutionism! Kill a few people but never mind, just tweak the algorithm! It’s… it’s indecent,” – his chair rocks forward – “the way you wash your hands of moral agency, when it is through your own technology that these futures are mediated.”

Bud waves a disdainful hand. “Now Floren, I’m sure we all read your piece in Armchair Ethicist Weekly, but this is about American industry. The real world, you get it? This isn’t the time for philosophizing.”

“Monsieur Carver, now is precisely the time for philosophizing!”

I have to step in. “Okay, so Alexandrine, I think we need to cover VW’s approach in more detail before the next licensing committee. I’ll ask the team to review with you next week.

“I guess we should move on to the final agenda item, which is HIMs of course. As you know, highly intimate moments in moving vehicles are mostly covered by states’ reckless driving or indecency laws. But, er, certain… media properties are concerned about moral corruption – tinted windscreens, mobile brothels, all that panic. So I need to bring Justice a recommendation that’s going to balance the realities of driverless time with this political aspect.”

Bud sits bolt upright. Crumbs fly from his mouth. “Gimme a break! Classic example of government meddling in the lives of ordinary people. Some guy wants to bust a nut in his car? Big deal. So long as it’s discreet, so long as it’s legal, let him.”

“Obv–”

“But nothing kinky.”

“Obviously our incognito mode disables internal cameras,” says Eric. “Or at least, it disables transmission anyway. But our view is essentially that this is just another connected device, and who are we to dictate use cases?”

“Discretion is important,” says Cecilia. “HIMs are, how should I say, seen as incompatible with our brand. As you know, we’ve disallowed adult content on the App Store for years. But also, people will do what people do. Our primary concern is inadvertent audio triggering by user vocalizations. I’ll have the Siri engineering team provide an update, although I can’t confirm whether such a team exists.”

“Facebook is keen to keep this area as loose as possible, Tom,” says Roosevelt. “As you know, intimacy has proven to be a surprising growth area for Oculus, and we think it would be a shame if overregulation got in the way of these exciting new forms of self-expression. Not to mention the potential constitutional issues.”

***

“Hi Meg. Good weekend?”

“Ah Tom. Yes, thanks. Kids up, so you know: zoo, tantrums.”

“So, you wanted to see me?”

“Yes, sit down. How are things with the ethics panel?”

“Fine. Still working with VW on their heuristics. They’re, well, they’re a long way behind. But Homeland have backed off remote disable for now: something about reassessing terrorism vectors, new strategy soon. We’re meeting again early next month. Tenth maybe.”

“Ok, well I have an update from my end. Seems Bud’s been talking to Dylan and the other vendors since the meeting, and… they’ve tabled a new approach. They’ve asked that we look again at self-regulation…”

“Oh, you’ve got to be—”

“…and DOT’s agreed we’ll suspend the delegation…”

“—shitting me!”

“…to let vendors choose their own approaches. We’ll monitor progress with DOJ, and—“

“They screwed me!” Shot a 77, then shot me in the back.

“Oh, don’t be melodramatic, Tom. Look, word is Don himself had a hand in it: jobs on the line and all that. You know policy priorities take precedence; not a lot we can do from our level.”

I shake my head. “Unbelievable. Wait, all of them? Floren?”

“Oh, Floren.” Meg laughs. “He’s fuming, of course, but Legal waved the NDA and he calmed down.”

“Motherfuckers.”

“Look, Tom, I get that you’re upset but really, I think the ethics thing is overblown. These guys are innovators, remember? Smart people. It’s not good business for Silicon Valley to do unethical things; the market will iron out any misbehavior.” She pauses to sip her coffee. “And besides, if things do start out a little hairy, we still have plenty of budget for signage and public information programs.”

The improbability of Alex Hales

Occupying as it does the fragile months of the summer, English cricket is deeply influenced by alcohol. While football terrace prohibition causes binge-drinking before kickoff, cricket presents a daylong test of boozy stamina. Cup deposit schemes and zealous stewarding have made the beer snake an endangered species, but the cricket and a stag night remain the only places at which an Englishman can consider fancy dress.

This does not make for precise memories.

Ah, but I forgot. You Americans, you don't understand cricket. Actually, you relish not understanding it, this daft tortoise game of bad teeth, straight elbows, and dinner etiquette, as enacted by Britain and Her Colonies.

But you like baseball, which makes explanation surprisingly easy. Cricket is baseball but really, really hard to get someone out. While baseball outs tumble like autumn leaves, a cricket 'wicket' is a gleaming butterfly on a spring morning. Hundreds of runs are scored. A game lasts five days. This, you begin to understand, is why we drink.

I watch quite a lot of cricket, mostly Middlesex and England. (These deserve nominative elaboration. Middlesex are a London-based team named after an obsoleted county; the anachronisms pile up quickly in this game. The team called England is the responsibility of the England and Wales Cricket Board, allowing me as a Welshman to pledge allegiance.)

I drink less than I used to, as maturity has grown and my tolerance dropped. But it’s fair to say that cricket's longitude and consumptions, and my woeful memory, have made my cricket memories melt together. It's been marvellous, sunburned, imprecise fun; I've seen no-balls, legends, centuries, dogged controversies; but I'd struggle to recall exactly when and where and who.

Until last week.

England batsman Alex Hales has had an awful summer. On the brink of deselection, he was a man at war with own psyche. With a game based on quick scoring, on aggression and active intent, he too often has lacked the technique and patience required of an opening batsman. Just one week ago he played perhaps his worst ever England innings, staying in just long enough to, in the words of one commentator, look really bad.

On Tuesday his luck was in. A one-day match at his home ground, Trent Bridge, against a Pakistan team that excels at the five-day game but is short of quality in the short stuff.

Tuesday's game will stick around, unlike others, because it broke all-time records. Hales played perhaps the worst best-of-all-time innings I've seen, swiping the bat recklessly, bisecting fielders with mishits. Commitment and luck overruled control and timing. Cat-like, he survived many deaths, including a dropped catch and a dismissal reversed by a no-ball. Dancing on the knife edge of fortune, Hales was electrifying. His partner Joe Root, the world's leading exponent of eloquent batting, capable of exquisite shots that catch your breath like only great poetry can – looked ordinary in comparison.

By the time he finally yielded his wicket, Hales had scored 171, an English record. And England themselves weren't done. Hales's departure brought in Jos Buttler, a known slogger, who feasted on some poor Pakistan bowling to rack up a lightning 90 not out. Buttler too rode his luck, clean bowled at one point but – to whoops around the ground – recalled after the TV umpire declared another no-ball. With his last stroke, Buttler hit the boundary that sealed the all-time record score. England ended on 444–3 off fifty overs; a score unfathomable a generation ago.

Hales is a vigorous but fragile player who threw caution aside. Batting form moves slowly, as befits this intensely slow game. Recovery often requires a spell out of the limelight, some time playing to tiny crowds in domestic cricket. Rarely do we see a transformation this abrupt. It's easy to overplay the triumph-of-the-human-spirit angle, but Hales was somehow able to shed his mental shackles for a day and produce something extraordinary. He has not cured his technique issues. He may yet not be the man England need as a Test Match opener. But for one day, the world truly rotated along his axis. And to be there was to witness a day when cricket surpassed itself, that became not just about sunburn, cider, and cheers, but genuine sporting improbability.

“It can be a cruel game” Hales said afterwards, “and it can be the best game in the world."

Inherent and acquired diversity

[Capturing a tweet drizzle in a better format.]

There are actually two dimensions to diversity. One is ‘inherent’ diversity in traits such as gender, ethnicity, age, sexuality. Lots of welcome focus on improving this through recruitment practices, addressing bias, etc.

But poor decisions can also stem from a lack of ‘acquired’ diversity: a homogeneity of backgrounds, languages, life experiences. This gets easier as you get older / richer / more senior – more breadth, more travel, more inputs. But it's also a personal responsibility.

So, people of tech: Travel! Learn new languages! Hang with people outside your socioeconomic group! Work abroad! Dabble! You’ll become a more rounded person with broader and more useful perspectives. And you’ll have a lot of fun too.

A 🔒 user wisely points out those are privileged prescriptions. True. But please, friends, broaden your perspectives if and however you can. Because we don’t need more stupid tech decisions caused by a lack of thinking, a lack of perspective. Our industry is going to demand an enormous amount of user trust over the next couple of decades. Let’s start justifying that trust today.

Past and futures

From this terrible hotel room in this unlovable town, the outlook is bleak. The twin disasters of Brexit and Trump look not just possible but likely. Orlando is still naming its dead. The Euro 2016 football tournament has fractured into violence.

To ascribe common cause is to oversimplify, but in all of these acts I see the influence of the past. The Trump and Leave campaigns alike fixate on restoring former glory. Some people wish so much to deny LGBT people their contemporary freedoms that they will murder to revoke this progress. Even the Russian hooligans have targeted English fans based on a reputation twenty years out of date.

Meanwhile, youth culture continues to fetishise bygone eras, and when the kids grow up they emerge into a thriving mainstream retro culture. Garden parties for the Queen. The infantilisation of adult colouring books. Keep Calm cupcake fascism.

The past has a lot to answer for.

We technologists prefer to focus on the future, sketching out how things might be, wondering how to improve matters both trivial and significant. Imagining bright futures can make us prone to melancholy about the present, and today that sadness feels particularly strong. To see the world take conscious steps to mimic a past that has evaporated (if it ever existed at all) … it’s agonising.

Part of that agony comes from realising it’s partially our fault. We’ve failed to convince millions of people the future will be better. Our intentions and excitement have left people cold, or even hostile, to the extent they would rather chase an impossible reversion.

Progress will always create winners and losers, but we ignore the scary and disenfranchising potential of our work at our peril. What Silicon Valley wants is often not what the wider world needs. The past has a lot to answer for, but then, so does the future.

Reflections on Japan

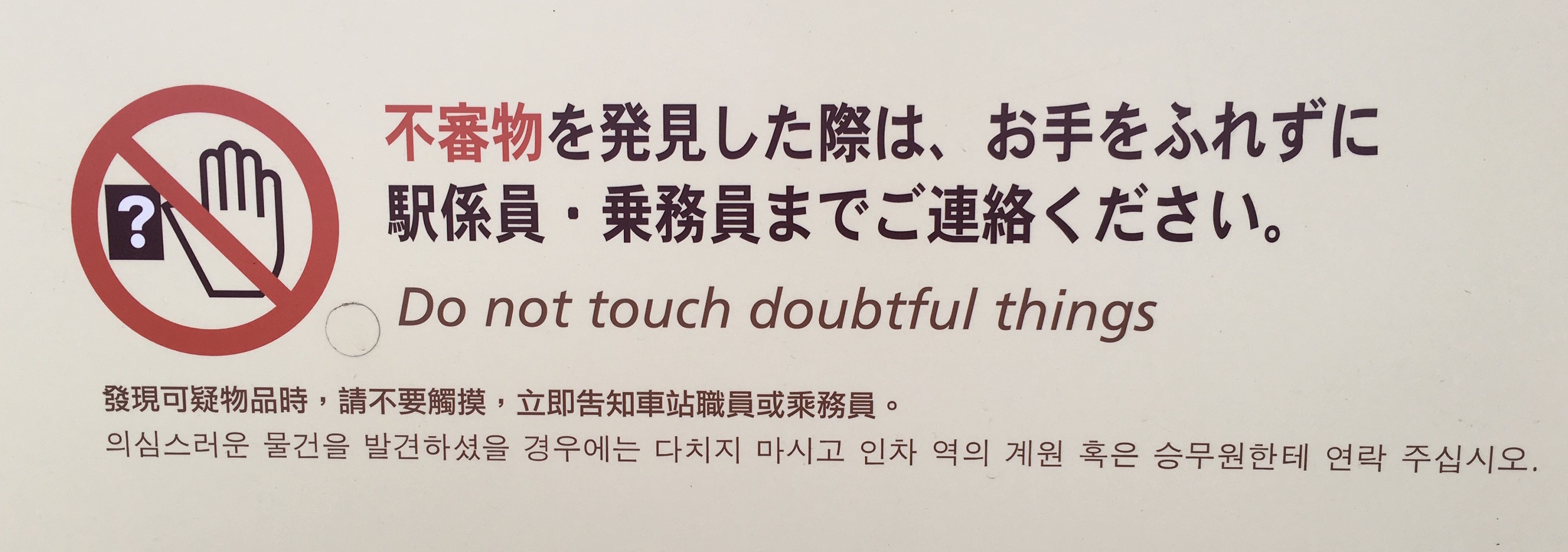

The West still looks at Japan in infantile ways. It’s all a bit Early Internet, of an era when user-generated content was viral and heady: look at what those crazy Japanese do. But the wackiness fades quickly and, embarrassed at my inarticulate arigatou gozaimasu arrogance, I find the mistranslations more generous than hilarious, although some are still charming.

Yes, there’s a street that sells wax food, but it’s knowing – the retailers know it’s a tourist attraction now, so they also sell nigiri keyrings and iPhone cases with tempura protuberances. I head to the Ghibli museum sceptical, fearing queue-for-a-photo-with-Totoro pandering, but the place is detailed and charming. Fragments of Japanese mythology, coal dust, tatami.

We eat well, five-figure blowout and starchy backstreet okonomiyaki alike. My fingers stain with soy and umami, although I draw the line at the fish eyes. We make makizushi and you know, it’s pretty easy. Like brushing a cat, you need more force than you’d think. Mix the rice with a slicing motion, and wipe the knife with each cut. I learn I prefer red miso to white, and that Japanese desserts aren’t for me: too little sweetness and crunch, too much paste. At the tiny Ginza sushi bar I simper as wasabi steam rises in my nose, but the guy has a damn Michelin star so I’m hardly about to disagree with his methods.

There is something about Zen, isn't there? Simplification, purity, doing one thing well: I can see why artists like it. Rituals abound. The tea ceremony is exactly ceremonial, all genuflection and cleaning and not much tea. Do you bow at the temples? I'm not a religious man, and decide it could be insulting to pretend otherwise. But enough people are doing the suggested motions, tossing loose yen into the grate, clapping twice, purifying the air with the bell. What's the difference between a shrine and a temple anyway?

Very little appears to happen by accident. The tarmac is immaculate, emblazened with sturdy ideograms, begging for the glide of streamlined bicycles and heavy suitcases. No lawn is unedged. The Japanese clearly love infrastructure: even the most trivial roadworks employ glowsticked security guards. While we Brits love engineering as historical badge of honour – the first railways, mate! Victorian sewers! – we’ve no interest in doing that kind of thing any more. Tokyo shrugs and lays another kilometre of seductive tarmac.

We buy niknaks that fit our too-small suitcases: stickers, biscuits shaped like pigs, useless soy saucers that fall into the “believe to be beautiful” category. Japan’s precision is infectious, but I know within three months I’ll be my old mess, sticky tape, beer caps and neuroses. I'm not sharp enough for this lifestyle, but that's okay: it's not mine.

Service is deferential and sexless, excepting perhaps Shinjuku's more lurid alleys. My wife’s game attempts to speak Japanese receive gratifying forgiveness. (I’m in France next month, so I enjoy this compassion while I can.) We drink with an ex-pat friend at an Okinawan bar, at which we're offered pickled snake juice, a staff-uniform kimono, and countless cups of sake. We roll out at 1am, the owners pressing business cards into our hands and waving us down the street. At 100 metres we sneak a backward look and, sure enough, they're still waving.

As a tourist, tourists are agonising. We’ve missed the best of the blossom season, but a few late bloomers linger in the parks, smartphonistas crammed in anticipation of Instagram hearts. It seems Chinese tourists are the new American tourists, barking at us to vacate their viewfinders, dressing in tacky polyester kimonos at the shrines, brandishing selfie sticks. I’m cool with selfie culture, but I'm no fan of the me-plus-landmark photo, a pic taken purely for documentation, to confirm presence, rather than for any recognition of beauty.

In our brief countryside stopover, the birds are different. Even the oblate sparrows, probably pests here, are captivating. I spy a yellow wagtail on a power line. I don't know birds, but it was yellow and wagged its tail. Our ryokan’s alpine tranquility is punctured by lingering jetlag and a pillow made of rock. I fidget half asleep, haunted by Suntory Boss's monochromatic face.

Finally, one last night in Toyko. Megacities are really about night-time: the 34th storey views, red eyes blinking on skyscraper shoulders, and advertisements blooming on the horizon like frozen fireworks. The photos never come out right, but I turn the lights off and press my face to the glass. In a gridless city everything below is Escher. I’m paying for the distance, for the vantage that helps me understand a city without having to be a part of it. Even this far up I can hear trains. Yoyogi Park is a blanket of darkness amid the light, and if I hold my gaze, the city really does twinkle.

What UX Designers Can Learn from Watching a Heron

As UX Designers we face constant challenges. As we wade through the lake of Poor Product Choices we must stalk our users/fish carefully. The path to UX Success demands that we strike with sharp-beaked efficiency – just like a heron I saw today.

So I’m on my honeymoon in Tokyo and we’re walking round a lake. “Do you see that heron?”, my new wife asks. And yes, I see it, but it’s a long way off, so let’s go round the other side to see it better. Except when we get there, I realise it’s a fake: one of those joke herons they put up to scare other birds away, although do herons eat other birds?

My new wife says look, its leg is moving. She’s right. But the heron still looks wooden. Animatronic? Japan does enjoy that sort of thing. No, no, the heron is real. Beak angled toward the water, neck arcing logarithmically, centre of gravity perhaps a foot behind it. A study in potential energy. This bird is about to go apeshit on a fish. I hope for keratinous knives spearing wet scales, a mouth gasping open. So we wait, obliged to witness nature at its most resplendent, most brutal.

A minute passes. The bird remains poised on its stupid legs, taunting gravity. Any moment. Any. Moment. The cliché: the minute you turn away, it’ll strike. Doesn’t matter: we’re going to win this one. Not going to be beaten by a fucking bird. Another minute. Two. Three.

The sun is bright today and my retinas scar over with a heron’s imprint. Tonight I will dream of olive-green bezier bird necks, beaks plucking at my eyes. And it strikes me that this is like UX, somehow.

No phenomena exist except me and the heron: my telekinetic beams versus its magnificent stasis. But… I lose, I lose. I move on. Suns will rise and set, dynasties will fall before this heron unfurls a wing. Later, as I lie in bed and write this glimmering thinkpiece, I deduce that the heron had, be it through genius or plain limbic stimulus-response, redefined the time axis. And thus I reach UX enlightenment.