Advice for people who aren’t exactly afraid of flying but aren’t exactly unafraid of flying either

[Like Craig Mod's post, but with a shade more neurosis.]

Routine is the key. Choose a decent airline, and downright insist on it. One of those Sir-and-Madam fading-glamour national ones tends to offer optimal predictability.

Collect frequent flyer points immediately: you might get the rare upgrade, but more importantly you'll probably get to choose your preferred seat (see below).

Fly business or premium if you can, of course. Check your flight a couple of weeks beforehand; if they offer you an affordable upgrade, grab it. Relief is valuable.

Get a bit drunk, if that’s your thing. It’s childish and unhealthy, but it does help. Just enough that you’d consider singing karaoke with good friends. Your fading-glamour airline should be good to dole out a couple of gins and tonic. Same drink every time, ideally: routine, you see.

Noise-cancelling headphones, drone/ambient music. No drums or vocals.

Craig is right: get to the airport embarrassingly early. But on top of that, check in everything you can. Minimal hand luggage. No see-through-bag hassles, no jostling for locker space.

Ignore the monitor telling you it's -70°C outside. Why the hell do they even do that?

Don’t kid yourself that a window seat will desensitise you. Pick an aisle seat close to the front (less fuselage flex) and look ahead.

Friends who wish you a safe flight don’t realise they just reminded you that flying might not be safe, something might go wrong and you’ll just be falling and falling and falling. Forgive them.

Trust in science and training and rationality. Like, there are people who are on these things all the time and they’re still alive and happy so, y’know: probability theory. The BA Airbus 319 has a bulkhead pattern of tiny notches if you want to visualise what 1 in 100,000 looks like.

The plane wants to be in the air, and it wants to be stable. It’s the natural equilibrium state: swimming in the air. Flying is only scary because the air is transparent. Imagine the air were blue. An ocean of buoyancy. Peace and happiness. Turbulence is just like a truck bouncing on a road. Little pockets of squelchiness, that’s all.

Text your wife (etc) as you board and once you land. Tell her you love her. Use emoji.

oh fuck what the fuck was that oh okay it’s just the drinks trolley

If you can sleep, then for goodness sake sleep, you detestable bastard.

Viewfinder

Don’t trust a designer who can’t take a good photograph. A smartphone shot is fine: never mind the f-stopping and ISO-juggling.

Just enough to demonstrate they can manipulate light, shape, contrast, balance, mood, gaze, proportion. Enough to prove they see.

[for the avoidance of doubt, this is not a good photograph.]

It's not what you think

I started a “Lessons learned at Twitter” post, but I think there’s just one big one: It’s Not What You Think.

We all know Hanlon’s Razor:

Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.

Here’s my preferred extension:

Never attribute to stupidity that which is adequately explained by complexity.

To work somewhere like Twitter is to face perpetual speculation. A hundred bug reports from a hundred friends; press flattery in hope of a careless divulgence; the odd phishing attempt; daft exegesis of blog posts.

And, y’know, that’s fine. A minor downside of notability, compensated by big upsides. You adapt. You shred your sketches, turn on two-factor, and lean on your Comms colleagues: the company knows speculation assumes its own trajectory, and you don’t want to fuel more nonsense.

In my three years at Twitter, I found perhaps 95% of the speculation about the company’s motives was wrong. Laughably so, at times.

These theories always assumed commercial motives: Here’s Twitter’s Masterplan To Dominate Whatever in Proxima Nova Bold 36px. Some conspiracies originated from cui-bono sources that depict Twitter’s business model as evil for the benefit of alternative business models.

When the profit interpretation didn’t fit so well, the fallback was simple incompetence. If only they’d do whatever, they’d make billions. Why does no one in that idiot company stand up for users?

The truth was sometimes mundane, sometimes highly faceted, and frequently hidden in a blindspot only known to someone who’s worked at that scale. The hair-tearingly obvious option would harm another set of users. Or it would be too expensive: a simple lookup that becomes extortionate when run 10,000,000 times. Or it would open up nasty new spam vectors. Or it would suppress emergent user behaviour the team wanted to explore. Or it had already shipped as a small experiment, just not the one the press had seized upon.

Even the few commercially-oriented decisions were greyer from the inside than out. Twitter employs a few thousand intelligent people who excel at robust, eloquent, mostly civil debate. No opinionated employee will agree with every exec-level decision – the choice is then whether to fight to the death, or acquiesce and progress. This usually isn’t a tough evaluation: no point thrashing around once wheels are turning.

We shouldn’t give large companies a free ride. It’s no secret that Twitter has some problems, and it’s right they’re in the spotlight. But let’s also recognise that it’s furiously difficult to make products of global significance, particularly in juvenile companies. The corpuscles of even the most faceless megacorp are people: people who are talented, who are listening, who agonise over their work more than you’d believe, and are desperate to do the right thing. Sometimes they succeed, sometimes they don’t.

Our readiness to assume conspiracy by default is one of the 21st century’s saddest trends: perhaps it’s time to venture good faith.

[Disclosure: I still hold a small amount of Twitter stock. I proffer no advice on whether you should invest in the company yourself.]

Recipes

I like my martinis dry, and my team ratios approximately

- 1 product designer to

- 1 product manager to

- 5 user-facing engineers, including a lead

The balance is important. Too much design and the mix gets sticky and saccharine. Too much product makes for a headstrong, imbalanced taste. Too much engineering and the acidity of velocity overwhelms everything.

Stir well.

Types of goal

Some goals are pure rapture, of course. Advert goals. Cup Final winners, sure, but a Tuesday night equaliser can qualify if the harmonies are right. A narcotic fizz. Players wrestle to the ground five metres away, sweat and spittle bursting in the floodlights. Someone topples over from the seat behind; you pull them up by their jacket sleeves. No hot chocolate remains unspilled. Goals that cause good-natured injuries you compare on the train home. Goals you YouTube when you can't sleep and damn: raised hairs every time.

But there are other goals.

Some goals come too late: 4–0 down and damn, finally. It’s important to know the appropriate cheer for this goal, i.e. the wayyyyy that accompanies an English pub plate-drop. The player sprints back to the centre circle with an armpitted ball, pretending to the manager he’s not given up. This goal doesn’t even need to be a goal, if you’re sufficiently desperate. Late in a grim mid-table season it can be fun to fake it: “Let’s pretend / Let’s pretend / Let’s pretend we scored a goal!”.

The goals when you’re 4–0 up happen less frequently. They’re almost embarrassing. Home fans are already grumbling to the exit, and your fullback gets his one for the season: a defensive howler that even he can’t miss from two metres. More of a basketball cheer: staccato, fading to applause and grins. A tenner in an old coat.

Some goals you’re not terribly proud of. That guy in Block 120—yeah, him—has been giving you wanker signs all game, and the blood alcohol takes over. Have some of that, you prick. Plosives and pointing and swear words. The sort of overlubricated goal that foretells a looming 8pm hangover and misspelled texts.

Some goals are amused disbelief: 3:06pm, one up against Man City. You jump around of course, but you know it’s ludicrous and temporary. Enjoy the outlandish story but don’t let it become too real. Self-protection, see.

And then there are the goals the other team scores. Those are never fun.

New workshop: Visual Essentials

I moved into full-stack* product design a few years back. Ever since, people ask me how it went, how I did it, and confessed sotto voce that they'd like to do the same but don't know how to start.

I think I can help. So I've set up a new training workshop called Visual Essentials for Product Design.

It’s is aimed at people with some design experience (web, interaction, user experience) who want to improve their visual design capabilities. Perhaps they want to collaborate better with their visual colleagues, or maybe they want to move more toward full-stack product design themselves.

The workshop is hands-on: 50% of the day is spent doing and critiquing. The rest is made up of some relevant theory, and a large number of tips and shortcuts that I learned the hard way.

Since this is a new workshop, I want to prototype it first. I'll be running a limited-attendance half-price event in London this summer, before rolling it out fully wherever there's demand.

If you're interested in attending the prototype in London or the full workshop anywhere in the world, sign up for updates. If you’d like to talk about bringing the workshop to your team or at your conference, drop me an email. Or if you’re feeling otherwise generous, please spread the word!

Visual Essentials for Product Design is the first of a small series of workshops covering a range of contemporary digital product design topics. I’ll share more on the companion workshops in the next couple of months.

* Ugly phrase, but it communicates well enough.

Tips for speakers

Mostly as an aide memoire for myself, but perhaps these might be useful to others too.

- Be the one thing an organiser knows can’t go wrong. Bring a laptop, a charger, a reliable dongle. Buy a clicker. Don’t borrow one. Don’t use a mobile app. Buy a clicker.

- Move a handheld mic as you turn your head, dammit.

- Run lapel mic wires underneath your shirt.

- Assume a mic is live, except when you want it to be.

- Make sure you’re muted before that nervous pre-talk pee.

- Put your wallet, your lanyard, your phone, your watch into your bag. Hide the bag out of sight.

- Put your laptop into Do-Not-Disturb.

- Back up your presentation to Dropbox, USB, or both. Fonts and videos too.

- Ask for water. Drink it onstage.

- Get there early to reassure the organisers you’re there. Walk around the stage to get a feel for the room.

- Speak slower. Pause. Control the presentation.

- Rehearse. Again. And again.

- Q&A is awful: avoid if at all possible.

- Ask for money. Try 5× the ticket price as a rough guide (for a single-track event).

- Don't be so precious about money that you won't negotiate.

- Favour events that have a Code of Conduct.

- Soundcheck.

- Present off your own laptop or risk disaster.

- The latest version of Keynote is fine now.

- Don’t drink too much at the speakers’ dinner. But one extra at the after-party is fine.

- When someone tells you they really enjoyed your talk, smile and say thank you.

Open and shut

Ev Williams wrote an important article, Sometimes things stay stuck, in response to a tweet storm from Chris Dixon.

We often hear the idea that “open platforms always win in the end”. I’d like that: the implicit values of the web speak to my own. But I don’t see clear evidence of this inevitable supremacy, only beliefs and proclamations.

As Ev argues, there’s plenty of case history of media going the other way—open to closed—and staying that way. And I’d argue this becomes something of a one-way valve: once systems become closed, profit potential tends to grow, and profit is a heavy entropy to reverse.

I worry the web community underestimates the power of capitalism, its sheer mania to sustain itself. After open technologies blew away some weak industries, it was tempting to believe the web would stomp through others just as easily, pushing aside the creaking bones of tycoons and corporations alike. But we now see that when open technology and capitalism do go head-to-head (1), it’s a tough old scrap.

Let’s be clear: the open web is not winning. Today’s most significant tech products and companies are not web-based (2): they are building on proprietary mobile platforms (I include Android here). The ideas, the transformation, the growth are all happening on the closed side. The talent is increasingly moving there, and the money has long since chosen its allegiances. The open web isn't outright losing yet, but its goalkeeper has been sent off and there’s a free kick just outside the box. (3)

I do think there will always be a role for an open web. But it may never again be the primary platform for tech innovation. That’ll be a shame for sure, but I’m a pragmatist and I don’t believe platform sentimentality helps us much. Ultimately, I vote for whichever technology most enriches humanity. If that’s the web, great. A closed OS? Sure, so long as it’s a fair value exchange, genuinely beneficial to company and user alike.

(1) They don’t have to battle, of course. There are companies that seek profit from open systems. But here I’m talking about companies that seek profit from closed systems.

(2) Well, some would argue they are, if you employ a particularly broad definition of a web-based product. For the sake of this post, my quick stab is “a product you can access by typing a URL into a browser”.

(3) I hear geeks love sport analogies.

What we call our cat

Beemo · Beems · The Mo · Beemster · Peems · Boomtown · Boomer · King Moggle Mog · Softness · Cwtchcat · Satan Cat · Wizard Eyes · Meow · Noise Box · Little One · Idiot Cat · Beemochu · Motown · Loafcat / Catloaf / Loafedy Cat.

Better OKR curves

Something I've learned the hard way about choosing OKRs and planning your team's priorities. Projects that only show late-gating impact, like this…

…are risky choices. Your team may do good work but be unable to show any impact due to, say, choosing to run another round of testing, an external dependency falling through, etc. Pretty demotivating. “Release [feature] and get Y% adoption” skews to this pattern, for any nontrivial feature.

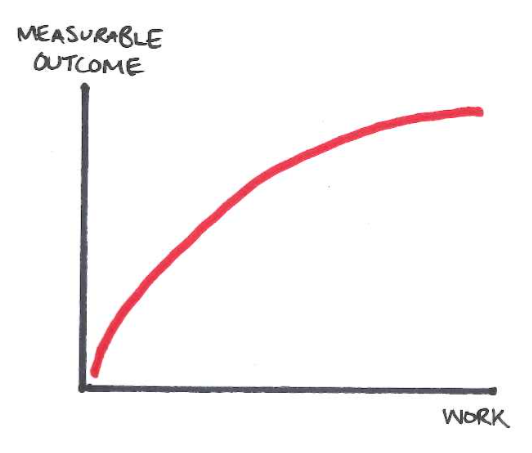

Diminishing-return projects like this…

…are just as bad. You’ve no incentive to go the extra mile. You get half-arsed and take your foot off the pedal.

Projects like this…

…are happier. People feel the motivating effect of their efforts having some impact, but there's also clear reward for excellence.

'Work' may be the wrong x-axis—Nik Fletcher suggests ‘Investment’, which I like—but hopefully you get the idea.

Moving on

I’m leaving Twitter on 2 April.

I think once you start wearing indentations into your keyboard it’s worth pausing for thought. It’s been a tough decision, but after nearly three exhilarating, demanding years I’m running on empty, and I need some time to reflect and recalibrate.

I’ll miss some of the brightest, most welcoming colleagues I’ve ever had. I’ll miss high-fiving the Hamleys bear on the way to work. I’ll miss enterprise software rather less.

No significant plans: some time off, then hopefully some writing, teaching, and travel. I’ll be looking for freelance projects or perhaps a full-time role after that. If you’re looking for a senior product designer or design manager, please get in touch. If not, please spread the word.

Void and matter

A thought by Allan Cochinov has been bouncing around my mind lately:

I’ve often theorized that there are two kinds of designers: those who like to design things smaller than themselves (appliances, sneakers, phones, book covers), and designers who like to design things bigger than themselves (architecture, interiors, city plans, cars).

How do digital things map to this model? Is our work large or small?

Well, both. Take Facebook: a damn 1,300,000,000-person megacontinent, sure, but full of microinteractions—the Like, a notification sound—that are smaller.

So we lean back with that knowing grin and explain that dimensions are passé. We contain multitudes. Nanometres and light years, man.

I tweeted that I don't really have a handle on what information architecture is these days. I’ve wilfully generalised over the past few years, and while I still get the tools of IA, the flavour of the thing, I can't grasp its boundaries, its definition. (As Karen suggests, it’s been a while since I’ve trolled myself.) I think I know the theory, but if I tell my colleagues we should work on IA and they say okay, what's that and how do we start, I don't know how to respond.

But maybe this model has something. Maybe IA is the larger-than-human stuff: the constructions that people inhabit. Topology, routes, flow. Doorways, light, maximum capacities. Designing the void.

And then maybe interaction design is the smaller-than-human stuff: the tools people manipulate. Materials with properties and responses. The time axis that makes 3d 4d: how you move and twist things, how they beep and complain. Designing the matter.

Designing the void. Designing the matter. Maybe.

Digital product design mentoring

[Update: I received a remarkable response to this offer – thanks to everyone who contacted me. I've now filled these slots but will post again if I have capacity in the future.]

Looking to take a step forward in the industry? I’m now available to mentor two new junior/mid-level designers.

You should be UK-based, preferably in London (but elsewhere in the country might work), and looking to improve as a full-stack digital product designer, rather than a UX or visual specialist.

I take an informal approach to mentoring, so there’s no set agenda, programme, or anything like that. You're the boss. But areas where I might be able to help include:

- careers advice, portfolio reviews, mock interviews

- helping you evaluate your strengths & weaknesses and construct a development plan

- advice on design tooling and software

- advice on design process (large and small companies, in-house and consultancy)

- help with specific design problems – although rest assured: you’ll still be the one doing the design!

- introductions to other community members or events as appropriate

After a while, my mentoring arrangements typically end up being very flexible and often simply become friendships with a designy slant.

My ideal setup would be to meet face-to-face every 6–8 weeks, with perhaps a couple of emails in between. And to be clear, this is a free offer – I don't charge for mentoring (sometimes people ask).

Please email me at cennydd@cennydd.com if you think this would be interesting. If I’m oversubscribed I’ll give priority to applicants from under-represented groups.

Opportunities

I made some money off the Twitter IPO. Not as much as startup mythology may have you believe, but a good amount.

While I’ve worked hard for my professional successes, I recognise that I've been playing on the lowest difficulty setting. My background, my education, and many other privileges have steered me toward the right place at the right time.

I see it as both a moral obligation and a simple pleasure to share some of my good fortune with others. Therefore I’m donating a sum of £9,000 to a range of causes I believe in:

Hopefully some of these experts can help make the game easier for others too.

I wavered about whether to speak about this publicly. The reason I’m doing so isn’t because I want praise, but because I hope it might prompt my friends and peers in this thriving industry to reflect on their own advantages.

I'll continue to donate to good causes as my future finances allow. I’d love it if you’d consider doing so too.

The Things of the Future

My 2011 (?) piece The Things of the Future, written for The Manual Issue 2, is now available online. It's definitely of its Occupy-flavoured era, but I still quite like it. It’s accompanied by The Lesson, a sad tale of foot-and-mouth and 20-something hubris.

Hunches about Material Design

A few reckons about Android L and Material Design spurred by yesterday’s Londroid event.

A few reckons about Android L and Material Design spurred by yesterday’s Londroid event.

Motion

Motion is the heart of Material Design, right? The visual aspects are striking but pretty straightforward, easily gridded / copied / 87% alpha-d. But even professional designers struggle with motion skills and tooling at the moment, and I don’t think we’ll see widespread quality motion for a year or two.

Initially I suspect most people will ignore it or just chain together stock Google animations – touch ripple, card lift etc – with blunt and sluggish results. Some people will proudly learn every cranny of a prototyping tool but not back it up with animation theory, resulting in a neo-Kai’s Power Tools era of ostentatious overanimation.

However, a very small group of talented people will nail Material motion, and name their goddamn price.

Professionalisation continued

Holo was mostly nouns, and constraining ones at that: grids, patterns, components. Material Design adds verbs, and they’re divergent ones: respond, flow, express.

The resultant syntax is more complete but more esoteric – possibly more than non-designers are comfortable with. I suspect Android is slipping beyond the grasp of the bedroom coder. It happens with every platform, and I dare say Google are fine with that. Teams will need more specialisation to create the sophisticated, professional apps that will help Android compete on UX. You’ll need to be a better designer to do great Material Design, but the possibilities are more exciting.

And it’ll be these strong designers (and their engineering & product colleagues) who’ll forge the real future of Material Design. Don’t expect Google to provide the answers. They’ve served up examples and inspiration, but the canvas is now too broad (particularly on devices we don’t yet think of as Androidy) for one company to own UX innovation. There's scope for anyone to set a precedent that others rush to copy.

Floating action buttons

Since this is the visual element that best signifies Material Design (and, by extension, cutting-edgeness), I think we’ll see thousands of the suckers. Most will straddle unnecessary borders, and most will overprioritise a single task. The floating button suits a primary action that’s very primary. Designers will still want to use them when that’s not the case, so I suspect we’ll see extra buttons added as qualifiers.

“Add!”

“Okay, add what? Page, post, image, address, etc”

“Play!”

“Okay, play what? Song, album, artist, radio, etc”

Radial menus and all that: their time has theoretically been due for at least five years, so maybe this is it. Could work if done well, or it could be awful.

Google definitely Get It these days. Anyone who’s been watching their design output for a while now won’t be surprised. It’s clear their culture is changing, and their mobile consumer products have improved at a terrific rate. I think Material Design shows some of the best platform design thinking in mobile, and it’ll be fascinating to see how their competitors (not least Apple) respond.

Technology NPS benchmarks

When reporting our most recent set of Net Promoter Score results to my team, I decided to dig around for some benchmarks across the industry.

When reporting our most recent set of Net Promoter Score results to my team, I decided to dig around for some benchmarks across the industry. This data's mostly locked away in expensive reports, but here's what I found from various public articles and PR pieces pimping said reports. These are mostly 2013ish figures, measured by third parties. Treat with hefty pinches of salt.

- Apple (laptops): 76

- FreeAgent: 72

- Apple (iPhone): 70

- Amazon: 69

- Apple (all): 69

- Apple (iPad): 65

- TurboTax: 54

- Google: 53*

- Netflix: 50

- TripAdvisor: 36

- Consumer hardware average: 32

- Blackberry phones: 27

- Microsoft tablets: 26

- Tech industry average: 25

- Consumer software average: 21

- Yahoo Travel: 14

- McAfee: 2

Unclear if this is just search or all Google products. Chris Collingridge has calculated an unofficial Google Search NPS of 79, albeit with likely sample bias.

A 'world class' NPS is 50+, with most companies across all sectors coming in between 5–15. A few outside the tech sector:

- Costco: 78

- Southwest Airlines: 66

- Marriott hotels: 62

- First Direct (UK bank): 62

- Tesco Mobile: 47

- American Express: 41

- Direct Line: 20

- HSBC: -13

Ideas and/or data

Design is a fantastic synthesis of ideas and outcomes, and will always be so.

Andy Clarke’s post What man, laid on his back counting stars… is a call to recognise the role of ideas and intuition in design. Bravo: we need more of this stuff.

Our industry has reached sufficient maturity to sustain different styles and schools of thought. This can only be a good thing.

My design approach relies on strong fundamentals: signifiers, metaphor, language. I thrive on improving a product over time through prioritisation, and helping a whole team see user experience as a shared concern. My favourite raw materials are user insight, strategy, design theory, and strong team relationships. This approach makes me reliable, if occasionally conservative.

I get the impression that Andy is more of a flair designer, thriving off sparks of creativity and inspiration. His raw materials will be different: perhaps they’ll be time, exploration, synthesis. That’s great. I’m a little envious of that style myself, but it’s just not me. If you want a Creative Director for your agency, Andy’s your man. I’d end up installing a different team and culture.

Andy’s article sets out a spectrum of design styles:

I see things a bit differently:

(I know I’m a manager these days because I find myself drawing quadrants.)

I add an extra axis because I don’t think product design means data-led design any more than web design means idea-led design. To me, the axes are orthogonal.

I should recognise some controversy here. Some folks dispute my separation of product design and website design, arguing they’re the same thing. I’m convinced they’re not, although I do agree there’s a continuum, not two distinct buckets. I’ll write more about this in due course.

Rewards

The approaches that succeed at company are largely a function of the company’s culture and lifecycle.

Data-based approaches tend to be highly valued in engineering cultures, sales cultures, mature product cultures, larger teams, and companies that have high volume and low margins.

Idea-based approaches tend to be more highly valued in entrepreneurial cultures, design cultures, companies with nascent products, and teams with lower volume and higher margins.

These aren’t fixed patterns, but I see them pretty often.

These valued approaches therefore change as a company evolves. Successful methods of a 50-person startup won’t work at a public company of 3000. As products and companies grow, they typically drift toward data-driven approaches. For that, we can thank capitalism and the nature of large systems: it’s easier to focus on reliable incremental improvement than risky reinvention. As we know, this can also blind a company, leaving it vulnerable to disruption from an idea-led competitor that attacks the problem in a new way.

What gets noticed?

Of the quadrants in my model, some get more attention, for sure.

It’s certainly true that the tech press is more interested in writing about apps than websites. Product companies are the ones talking about venture capital rounds, MAUs, hypergrowth: juicy American dream stuff. Website companies, less so.

But if anything, I think the industry is enthralled by apps built on ideas. The hot startups, the disruptors, the TechCrunch fodder are the companies building on an idea they hope will render their competitors irrelevant. Data-led product design is seen as something for the optimisers, the big boys, the unsexy. Adobe, Amazon, Facebook perhaps. These companies face a big challenge to retain their appetite for bolder bets. Some would argue the endeavour is likely doomed.

But it doesn’t matter what’s hot in the press. The four approaches in my model are all fundamentally sound. As with any discussion about beliefs, the danger lies in the extremes. It’s possible to become so invested in a data-only or idea-only approach that you become blind to the value of fitting your approach to the context.

Product design that’s driven entirely by data is horrible. It leads us down a familiar path: the 41 shades of blue, the death by 1000 cuts, the button whose only purpose is to make a metric arc upward. It’s soul-destroying for a designer. But its moderate counterpart, data-informed product design, is fine. It reduces risk, and encourages confidence and accountability.

Product design driven entirely by ideas is equally painful. The romantic notion of design genius and the Big Idea soon gets swamped by a culture of risk, favouritism, and blame.Idea-informed product design is fine. It provides agility, creativity, the power to see blindspots and seize opportunities.

I fully agree with Andy that we should never lose sight of the aspects of design that give soul to our work. These are just as prevalent in product design as they are in website design. Granted, they may manifest in different ways (mostly motion design for products, often art direction for websites), but design is a fantastic synthesis of ideas and outcomes, and will always be so.

Design’s not dud yet

Sure, utility is still the key outcome of design, but let’s not ignore its broader potential. Design can have aesthetic and cultural impact too, even if that is only to inspire designers working on more essential products.

[Some of our designers and PMs started an email thread about Mills Baker’s Designer Duds: Losing Our Seat At The Table. Here was my contribution, lightly edited.]

I agree with the majority of the post. There’s some wonderfully glossy and rather pointless design out there at present. But I don’t quite agree with Baker’s claim that success is to be judged only through utility and adoption:

“A “great” design which produces bad outcomes—low engagement, little utility, few downloads, indifference on the part of the target market—should be regarded as a failure.”

Great design can be an act of shaping culture.

Anyone who’s read Don Norman will know that Juicy Salif is not a good product by these yardsticks. It does not squeeze lemons well. It’s outsold by countless more functional, cheaper versions.

But it’s an important product in that it demonstrates that everyday objects can be playful, beautiful, surprising. I don’t think it’s a stretch to draw a conceptual line between Juicy Salif and, say, the Dyson Airblade: both are novel products that makes you reconsider the genre. Only one is particularly commercially useful.

Sure, utility is still the key outcome of design, but let’s not ignore its broader potential. Design can have aesthetic and cultural impact too, even if that is only to inspire designers working on more essential products.

![[for the avoidance of doubt, this is not a good photograph.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53cc84e7e4b0bcaba3c8b1ab/1431878834688-89Y4XI8LRGY47PFG0JCT/image-asset.png)