Announcing Undercover User Experience

At last, the big announcement. I’m delighted to confirm that Undercover User Experience, written by myself and fellow Clearleftie James Box, will be published by New Riders this autumn.

At last, the big announcement. I’m delighted to confirm that Undercover User Experience, written by myself and fellow Clearleftie James Box, will be published by New Riders this autumn.

Once you catch the user experience bug, the world changes. Doors open the wrong way, websites don’t work, and companies don’t seem to care. Fortunately, anyone can learn the UX remedies – usability testing, personas, prototyping and so on – but, unless your organization ‘gets it’, putting them into practice is trickier.

Undercover User Experience will show you how to do great UX work with tiny budgets, no time, and even without official clearance.

The idea came about in a Utrecht hotel, where James and I got talking about the early stages of our careers, when we didn’t have the luxury of doings things ‘by the book’. Through the IA Institute mentoring scheme I’ve met several people in the same situation. For them, what makes UX work difficult isn’t lack of skill, but not knowing how to make headway in companies that don’t appreciate the need. Pioneering UX and inspiring colleagues who’ve never cared about design takes improvisation, persistence and diplomacy. So we’ll cover guerrilla approaches to the UX techniques we know and love, along with frank advice on how to make them most of them in your business.

On a personal note, I’m thrilled to be partnering with New Riders. They were our first choice publisher due to their outstanding UX portfolio, including the classics Don’t Make Me Think!, Designing for Interaction and Elements of User Experience.

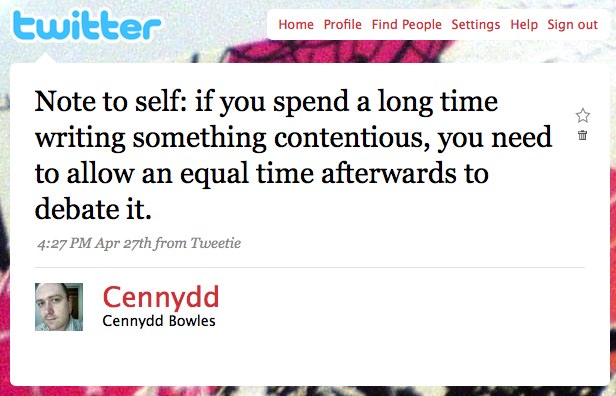

The writing experience is already demanding and rewarding. There’s been much to-ing and fro-ing over titles and much confusion over the US tax system and self-assessment, but we’re well under way and hoping to wrap the writing up by June.

But enough – I’ve no wish to turn this blog into a marketing vehicle. If you want to keep up to date with our progress and be the first to hear when the book’s due out, follow @UndercoverUX on Twitter or visit the Undercover User Experience website and sign up for updates.

!?

So far, so functional. However, chess notation also provides means of passing judgment on the moves.

It’s said there are more books about chess than all other games combined.

To non-players, a chess book is an arcane mystery of jumbled letters and references to openings with such exotic names as the Nimzo-Indian Defence, the Nescafé Frappé Attack, and the Sicilian Najdorf Poisoned Pawn Variation.

But notation is deceptively simple. Each move simply lists the moving piece and the co-ordinates of its destination. Be4 is a bishop move to a central square. Rxa8 tells us the rook is capturing whatever’s in the top-left corner.

(I’m talking here about algebraic notation. – the Pawn-to-Queen’s-Bishop-3 stuff of old movies – is deprecated as complex and ambiguous.)

So far, so functional. However, chess notation also provides means of passing judgment on the moves. Expert annotators earn their living by peppering games with punctational shorthand:

! – good move

!! – excellent move

? – bad move

?? – terrible move

These symbols can be combined. ?! denotes a dubious, but not awful, move. !? is used to mark an novel idea that looks promising but may prove to be unsound.

It’s the !? moves that I’m most interested in.

Map design in Modern Warfare 2

What makes MW2‘s multiplayer experience so rewarding? The answer is of course that the developers Infinity Ward have designed the game meticulously, in particular the maps on which the action takes place. By deconstructing these maps, we can attempt to understand the underlying gameplay design principles.

It’s no surprise that Modern Warfare 2 has broken records. Notoriety sells after all, but fortunately the game lives up to the hype. For devoted fans the single-player storyline, cause of the controversy, isn’t the appeal – it’s the multiplayer mode that’s kept gamers coming back for more.

What makes MW2‘s multiplayer experience so rewarding? The answer is of course that the developers Infinity Ward have designed the game meticulously, in particular the maps on which the action takes place. By deconstructing these maps, we can attempt to understand the underlying gameplay design principles.

The most obvious principle is that Infinity Ward have ensured there is no dominant position on any map. Advantageous positions of course make it easier for you to kill the enemy, and harder for them to kill you. Features of advantageous positions include:

- Elevation. This reduces your exposure, improves visibility and offers a better angle for headshots on the enemy

- Cover. A solid object to hide behind means you can pop up into firing position and quickly drop into safety to reload.

- Limited access. The fewer routes the enemy can approach from, the easier to spot attackers and quickly take aim.

and so on. To make the game fair and therefore enjoyable, game designers must use these features with caution. Omitting them would simply create extremely dull environments, so MW2’s maps make subtle use of these advantageous features, coupling strong positions with serious weaknesses.

This ledge on the Afghan map gives clear long-range lines of sight but is exceptionally vulnerable from the rear. At the far end of the map are reinforced bunkers, from which the following screenshot is taken. Cover and vantage are both good, and the low light leaves the shooter cloaked in darkness, making them hard to spot at distance.

However, since these bunkers are potentially very strong points, the map designer clusters two together, so that each poses a tactical threat to the other. To make these appealing spots even riskier, explosive barrels are placed in a particularly juicy spot, further deterring a player from camping there at least until the barrels have been destroyed.

(Camp (v.): To stay concealed in a safe spot and kill enemy players as they run past. Often considered a cheap tactic.)

For the few spots that offer clear tactical advantage without high vulnerability, Infinity Ward has wisely made reaching them a risky proposition. The Highrise map features a second-floor window (below) with excellent angles, low light and few weaknesses; however, it can only be reached by jumping around on dangerously high and sorely exposed crane beams. I’ve had many a profitable game repeatedly picking off beam-runners too stubborn to accept that I wasn’t going to let them reach their beloved camping spot.

Highrise also boasts a very unorthodox but effective position (‘A’ below), which allows a player to surprise anyone emerging from the southern building. Position A is suspended off the building on a platform and therefore hard to notice if you’re focusing on the more obvious threats near the helipad ahead. However, this excellent spot is awkward to reach and treacherous to leave. Your only exit route is to laboriously climb up over the side, leaving the player vulnerable for a few seconds – as such, once your cover is blown at A, you’re pretty much screwed.

By balancing the maps’ positions of strength, MW2 keeps players continually on the move as hiding spots become discovered and teams move to flank their opponents if repelled in a frontal attack. It doesn’t take an expert to see that movement makes for a more exciting game than static trench warfare; indeed, movement impetus and variable pacing is a well-known tactic of game design. By running around, players cover more ground and experience greater ranges of contact, from long range to hand-to-hand. In short, players are pushed into experiencing as much as the game as possible. Map scale also follows this principle. Although the maps are generally larger than MW2’s predecessors there is still ample variety, with both compact and sprawling maps encouraging bloody scrambles, patient stealth and all gameplay tactics in between.

Through prolonged play it becomes apparent that Infinity Ward also designed the multiplayer maps not to punish players for their choice of weapon and style of play. (Me? I hang back with the M4A1 or ACR, playing the percentage game with mid-to-long shots. I’m a poor run-and-gunner.)

As we’ve seen earlier, Afghan has some excellent sniping spots; but for those more inclined for close quarters combat, the map also features twisty cave areas and this tight rocky outcrop.

For those who enjoy a sneaky ambush, the maps offer plenty of safe havens and cover from which to spring. Terminal, set in an airport, offers some novel cover spots including this flower bed.

That said, some levels are better suited to some loadouts and styles of play. (Loadout = combination of weapons, perks and upgrades.)

This is healthy for the game, since it prevents a strong player sticking to the weapon and tactics they’ve perfected and dominating every map. Wasteland, for instance, is a sniper’s paradise.

This sort of position is close to ideal for a sniper: sure, it’s open, but the lines of sight are immense. Given this much visibility, even a modest sniper can pick off an unprepared enemy with ease. Short range weapons here are far less useful; however, Modern Warfare 2 offers players multiple ways to use territory to their advantage. For those who don’t like the patient precision required of snipers but want to use this spot effectively, the map designers helpfully place a machine gun nearby.

In the right hands the machine gun can be just as effective as sniping, rewarding those who get their kicks by spraying bullets indiscriminately. For the sake of equality, there’s a gun at the other end too and the long grass can quickly give a well-camouflaged player cover from fire.

This interplay demonstrates that every strategy has a valid counter-strategy. If you’re facing a sniper, the maps give many opportunities to hide. To counter this, snipers can flush out hiding opponents by using thermal sights and heartbeat sensors. To counter that, players can employ perks that make them invisible to these devices. Rock beats scissors beats paper beats rock. And for those who’d like to avoid this long range battle altogether, Wasteland also features an intense and dark section of trenches. Here, I’ve planted a Claymore landmine by one of the trench entrances to trap anyone who comes this way.

These indoor areas also give vital cover from the game’s aerial attacks, earned by successful killstreaks, for example killing five players in a row. At the first warning of an incoming enemy helicopter or Harrier, there’s typically a mad panic to get indoors. Skilled opponents will of course follow, but again the game provides an alternative to the hunt. Brave players can switch to a loadout armed with anti-aircraft weapons and perks and shoot the air support down for the good of the team. Thus good play gets its reward (air support usually brings many more kills) but not to the extent that it leaves the opposition team entirely devoid of options.

Through careful design, and no doubt thousands of hours of playtesting, Modern Warfare 2’s maps reward some surprisingly different approaches: caution and risk, patience and aggression, short range and long range. Admittedly the balance will never be perfect, and Infinity Ward are continually tweaking the game to overcome new glitches and overpowered strategies. But I consider Modern Warfare 2 a great example of thoughtful design achieving some difficult goals, and being clearly rewarded by the sales figures.

The best gig of my life

I’ve never felt so in touch with a machine in my life, and I doubt I will again.

It’s 2003 and I’m playing the best gig of my life.

The graduate slacker persona is getting old and we can no longer ignore the need for paying jobs, so it’s one last hurrah for old times’ sake. Local pub and a sympathetic crowd. I play the guitar, as all seven-year indie veterans do. A Stratocaster. Never did like Les Pauls. The mic craning in front of me indicates I drew short straw with vocals too, which I avoid by writing mostly instrumental songs.

A final nod and we hurtle into the opener we always play too fast. I realise that the weight of a typical performance is gone. No more worrying about whether people will come to see us again. Only the minutes matter.

We’ve abolished pauses between songs to sustain momentum and delay the audience response. It works. Our transitions are tight and the audience knows full well we’re teasing them. I see them grin. The songs sound demanding, you see, but they’re deceptively simple to play. The complexity is all rhythm, abstract numbers and melodic set pieces. Without fear of getting it wrong, a performance can rely on expression, not mechanics.

We pull into the new song on another wave of feedback. Two basses and a weighty tempo. As the intro builds, I keep my fingers away from the strings. We’ve practised so much that my fingers are sore, and I want to pounce at the last minute.

Then the kick in, blatantly telegraphed but somehow still a surprise even to myself. I shout something indecipherable and punch the pedals. It’s ecstatic. Not just the sound and the emotion, but the feel of the instrument. Frets worn down to just the right spot, strap lowered an inch a year as my confidence grows. I’m trying to beat the shit out of this thing and it’s responding. It could rebel at any stage, but it knows me and acquiesces. Even as it screams around the room, all fizz and distortion, I know I’m in command. I strangle its enthusiasm at the count of four, muting it sharply and jumping on the pedals with both feet. I hear a yell of appreciation, but it’s not for show this time. It’s a way to remind my guitar who’s boss.

I’ve never felt so in touch with a machine in my life, and I doubt I will again.

Eyetracking Web Usability: review

Remember those design principles you learned ten years ago? Eyetracking shows they’re right. Carry on.

Time to pick sides: Jakob Nielsen has written an eyetracking book. I can scarcely think of a more divisive pairing: mention either within earshot of a UX aficionado and you’re in for impassioned advocacy or scornful ridicule. Me? I’ll confess both subject and author have left me unconvinced in the past, but I approached Nielsen and co-author Kara Pernice‘s new book with curiosity and as objective an outlook as I could muster.

Eyetracking Web Usability is the outcome of the largest eyetracking study ever undertaken: 1.5 million fixations from 300 participants. Nielsen and Pernice are clearly keen to stress the magnitude and legitimacy of their research. Their test script, posted in full, is well considered and comprehensive, covering a range of tasks representative of real web use.

After a brief recap of eye physiology and saccades, the book begins in earnest with a detailed breakdown of research methods. Findings then stretch across chapters discussing specific web elements in turn: navigation, forms, images and so on. At their best, these chapters reveal flashes of usefulness. A chart of eye fixations versus layout density shows minimal correlation, demonstrating that busy pages simply dilute attention from the most important information. The book also touches on the important role of information scent and microcopy, declaring insightfully that “a link is a promise”.

In typical Nielsen style the text is heavily punctuated by summary boxes. Sadly, it quickly becomes apparent that these make the point just as effectively as the full text. Eyetracking Web Usability is all fat, no meat. Wasted space includes a page on why a 7-point Likert scale is better than a 5-point one, and five pages on male users’ propensity to fixate on dog genitals. The writing, meanwhile, veers from redundant to simply cringeworthy: “Give that Wii a rest, and go prioritise your Web page layout design. You can do it!”

A chapter on adverts (whose raison d‘être is of course to attract the eye) starts promisingly. An ad has a 36% chance of being seen by a user, a figure surprisingly unaffected by user task. However, it soon descends into known generalities: banner blindness and users’ dislike of irrelevant advertising. The chapter encapsulates Eyetracking Web Usability’s main shortcoming. Eyetracking demands specificity: carefully planned tasks on an individual site. Nielsen and Pernice’s 300-person test can only dilute potentially salient points into generalisations that even a novice designer will already know. The conclusions cover ground so well trodden as to be barren.

Despite the authors’ focus on rigour and transparency, serious concerns surround the research methods themselves. Heatmaps from the tests are dated from late 2005. With lab time accounting for five months, the study was therefore complete by summer 2006. Why then was this book not published until the brink of 2010? It is hard to avoid the impression that the results sat untouched for years and were subsequently rushed out in a lull of client work. Eyetracking Web Usability also misses a huge opportunity by focusing solely on informational websites. Web apps are discounted since eyetracking can’t handle dynamic elements, including Ajax and even dropdowns. The results are thus only valid for an increasingly small part of the UX designer’s 2010 workload.

Most worryingly of all, it seems that the tests were conducted in Internet Explorer 6. Browser choice does not appear to have been offered to users, and where browser chrome is shown (it is stripped in the vast majority of the heatmaps), it is unmistakeably IE6. If this is indeed the case, it nullifies many findings since the primary browser innovation of the 2000s – the tab – is unavailable. In IE6 a link is an entirely binary choice: go there, or stay here. Modern browsers allow an important new behaviour: Open In New Tab, creating tentative and plural navigation steps. It’s likely Nielsen’s participants relied far more on the Back button and their short-term memory than today’s users. Their search engine use is also likely to be different, since IE6 lacks an inbuilt search box in the UI.

Eyetracking Web Usability thus lacks the rigour required to be taken seriously as an empirical work; however, its adherence to factual reportage make it a chore to read. Even the most ardent enthusiast will skip over paragraphs that merely disclose participant actions in minute detail. It’s sixth form science at best; utterly literal, over-eager for the praise of the adjudicators. The effect is exacerbated by the disappointingly scant acknowledgment of others’ work. Few external insights or breakthroughs are admitted, although NN/g reports are of course suggested as ways for the reader to supplement his knowledge.

The book’s conclusion will come as no surprise to the reader. “Eyetracking fills in the details… Most companies should not bother conducting their own eyetracking studies.” It is hard to disagree. The book does nothing for the eyetracking industry except cement its status as an expensive diversion; the excessive cover price of £44 only reinforces this. If this is the accumulated wisdom of the largest eyetracking survey in history, we can safely consider the technology inconsequential.

Remember those design principles you learned ten years ago? Eyetracking shows they’re right. Carry on.

Looking back, looking forward

2009 has been kind.

2009 has been kind.

Professionally it’s been unsurpassed, despite the recession. Clearleft have grown to double figures, moved into a studio with decent wallspace, produced some great work, run two successful conferences and were humbled to be voted Agency Of The Year in the .net awards.

(Personally, I nominate UXCampLondon, Cardiff v Arsenal away and various ATPs, weddings and zombie crawls as additional highlights.)

As the office winds down, colleagues jet off overseas and lunches linger into the afternoon, thoughts turn to gifts and time off. Since I opt out of the commercial trappings of the season, I’ve chosen this year to make my annual donation to WWF and Reprieve, two fantastic clients I’ve worked with this year. I’ll be spending a unique Christmas on a military base. In lieu of ubiquitous WiFi, it’ll be an opportunity to spend time with family, read, write and get my breath back.

2010 will be a year of abundance – and the first casualty, sadly, will be my carbon footprint. I have three speaking gigs booked so far (South by Southwest, the IA Summit and UX London) and as a punter I’m hoping to grab a seat at Paris’s Content Strategy Forum, Berlin’s UXCampEurope and New York’s Design for Conversion. But of course 2010 is likely to be dominated by the book. Emails are a-flying and chapters are a-forming. More on that soon.

Thanks for sharing this year with me and here’s to the next one! Merry Christmas.

{PS. It’s also the done thing to list your favourite albums of the decade. In no order, I’ll throw out Michigan, Tarot Sport, Change, Turn On The Bright Lights and Leaves Turn Inside You.}

I blame the designer

In which Cennydd has a downright sense of humour failure over a silly web comic.

[In which Cennydd has a downright sense of humour failure over a silly web comic.]

Here’s an excerpt of a comic that recently did the rounds in the web design community.

You know what? I’m tired of this attitude.

Clients From Hell is admittedly pretty funny. Sometimes clients say stupid things; but hey, so do designers. I’ve said lots of them myself. But this sort of thing is different. It’s not an amusingly misguided email. Rather, it epitomises a harmful arrogance and entitlement that pervades the design community. It carries a bitter subtext that clients are idiots with no design skill, and it’s a designer’s duty to disempower them by any means possible.

And I’m tired of it. Of course clients aren’t skilled designers; that’s why they had the foresight to hire us. But you know what? They know business. They’re as passionate, committed and talented as anyone. Many of them put their livelihoods on the line to make the web happen. And let’s be blunt: they also pay our salaries.

If a web design project goes to hell this way, I usually blame the designer. He wasn’t skillful enough to make the situation work. He didn’t provide the force of argument required, couldn’t handle the politics, or couldn’t convince the client of the value of good design. On the rare occasion when the relationship with a client goes entirely rotten, the designer should end the relationship gracefully rather than passive-aggressively working to rule.

Unconvinced? I suggest you read Scott McCloud’s excellent post about criticism and the equally insightful comment from Mike L:

“The most common misconception about criticism is that one has to be on a similar skill level as the creator in order to have a valid opinion. I read stuff from many different artists from many different disciplines who cannot abide ramblings of people that couldn’t compete with them in some way. If said person is not an artist, their opinion doesn’t matter. But isn’t art, all art about communication? And who is the artist generally trying to communicate with? … My #1 critic is someone who cannot draw at all. He tells me things I can’t see because I overthink them as an artist.”

(Oh, and here’s what ‘pop’ means.)

Statistical significance & other A/B pitfalls

It’s logical and laudable that designers should seek data in our quest for verifiability and return on investment. But data must be handled with care, and mathematical rigour isn’t a common part of a designer’s repertoire.

Photo by snellgrove.

Last week I tossed a coin a hundred times. 49 heads. Then I changed into a red t-shirt and tossed the same coin another hundred times. 51 heads. From this, I conclude that wearing a red shirt gives a 4.1% increase in conversion in throwing heads.

A ridiculous experiment (yes, I really did it) with a ridiculous conclusion, yet I sometimes see similarly unreliable analysis in A/B testing.

It’s logical and laudable that designers should seek data in our quest for verifiability and return on investment. But data must be handled with care, and mathematical rigour isn’t a common part of a designer’s repertoire.

Here’s an example from ABTests.com, a worthwhile project that I feel slightly bad to pick on.

The two versions are subtly different:

- Version A: Upload button bold, Convert button bold, Convert button has a right arrow

- Version B: All buttons regular weight, no right arrow on Convert button

Although minor changes can cause major surprises, I wouldn’t expect these small differences to improve the form’s usability. With the caveat that I don’t know the users or product, I’d even speculate that Version B could perform worse since it reduces the priority of the calls to action and removes the signifier of progression.

The designer claims that version B showed a 30.4% conversion improvement in an A/B test. Here’s why this isn’t quite accurate.

The role of chance

Any A/B test is a trial, so called because we’re observing evidence gained by trying something out. I can never truly know that there’s a 50% chance of a coin landing as a head or a tail – I can only run trials and observe the evidence. Similarly, we can never truly know that a design leads to higher conversion – we can only run trials and observe the evidence. If that empirical evidence is strong enough, we conclude that the design is an improvement. If not, we don’t.

To be valid, trials need to be sufficiently large. By tossing my coin 100 or 1000 times I reduce the influence of chance, but even then I’ll still get slightly different results with each trial. Similarly, a design may have 27.5% conversion on Monday, 31.3% on Tuesday and 26.0% on Wednesday. This random variation should always be the first cause considered of any change in observed results.

The null hypothesis

Statisticians use something called a null hypothesis to account for this possibility. The null hypothesis for the A/B test above might be something like this:

The difference in conversion between Version A and Version B is caused by random variation.

It’s then the job of the trial to disprove the null hypothesis. If it does, we can adopt the alternative explanation:

The difference in conversion between Version A and Version B is caused by the design differences between the two.

To determine whether we can reject the null hypothesis, we use certain mathematical equations to calculate the likelihood that the observed variation could be caused by chance. These equations are beyond the scope of this post but include Student’s t test, χ-squared and ANOVA (Wikipedia links given for the eager). Here’s a site that does the calculations for you, assuming a standard A/B conversion test with a clear Yes or No outcome.

Statistical significance

If the arithmetic shows that the likelihood of the result being random is very small (usually below 5%), we reject the null hypothesis. In effect we’re saying “it’s very unlikely that this result is down to chance. Instead, it’s probably caused by the change we introduced” – in which case we say the results are statistically significant. Note that we still can’t guarantee that this is the right interpretation – significance is about proof only beyond reasonable doubt.

Running the calculations on the above data shows that the results aren’t statistically significant: the evidence isn’t strong enough to reject the null hypothesis that the difference in conversion is simply down to luck. The main problem is the small sample size (128 and 108 users respectively), so I would advise the designer, Johann, to repeat the test with more users. Assuming the observed conversions seen didn’t change (a big assumption) a sample size of approximately 200 users per variant should be sufficient for significance. He could then either reject the null hypothesis or the results would remain inconclusive, in which case there’s no evidence the design has made a difference. In Johann’s defence, he recently posted that he takes the point about significance, and I’m looking forward to seeing more conclusive data for this intriguing test.

Percentage confusion

Significance isn’t the only slippery problem A/B tests face. For starters, quoting conversion improvements is always fraught with difficulty. Since conversion is usually measured in percentages (in this example, 31.3% and 40.7%) there are two ways to quote improvements. We can say that conversions increased by:

- 9.4% – the difference between the two

- 30.4% – the amount that 40.7% is bigger than 31.3%*

Any percentage improvement quoted in isolation should be challenged: which of these two calculations has been used? It’s dangerously easy to assume the wrong figure without sufficient context.

The A/B death spiral

A/B tests also suffer from a common quantitative problem, in that they tell us what but not why. I’ve written about this previously in What if the design gods forsake us. It’s wise to back up numerical tests with qualitative evaluation (eg. a guerrilla usability test) so we can make informed decisions if data suggests we need to rethink a design.

Even with backup, sometimes A/B tests are simply the wrong tool for the job. They can provide powerful insight in some cases, but in the wrong place they can be a blind alley or, worse, a weapon of disempowerment. Logical positivism and design don’t mix – not everything we do can be empirically verified – yet some businesses fall back on A/B testing in lieu of genuine design thinking. I call this the “A/B death spiral”, and it plays out something like this:

Designer: Here’s a new design for this screen. You’ll see it has a new navigation style, tweaked colour palette and I’ve moved the main interactions to a tabbed area.

Product owner: Wow, those are pretty big changes for such a high-risk screen. I tell you what: let’s test them individually to see which of these changes works and which doesn’t…

As the proverb suggests, sometimes you can’t jump a twenty foot chasm in two ten foot leaps. Cherry-picking only those design elements that are “proven” by an A/B test can be a route to fragmented, incoherent design. It may earn marginally more money in the short term, but it becomes hard to avoid a descent into poor UX and the long-term harm this causes.

Being faithful to data

Given the potential hazards, I’m concerned about the naïveté with which some designers approach quantitative testing. The world of statistics rewards an honest search for the truth, not dilettantism, and I’d advise any designer moving in statistical circles to pick up some basic stats theory, or at least partner with someone knowledgeable.

A flawed A/B test, be it statistically insignificant, misapplied or misquoted, is nothing more than anecdotal evidence. It’s the same crime as making a website red on the feedback of one user. Yet an impatient designer, seeing the example I quoted above, could quickly jump to a false conclusion: “I should remove arrows from continue buttons: it’s 30.4% better.” Perhaps this designer deserves what he gets. It’s likely he’s only really interested in shortcuts to good UX, and linkbait lists of “Twelve ways to make your site more usable.” Since he understands neither the mathematics nor the context of this trial (timescales, userbase, surrounding task) he will inevitably grab the wrong end of the stick. Nonetheless, he is out there.

Don’t let yourself be that designer.

* subject to rounding

Q&A: getting into user experience

It’s not that surprising to find that a room of similarly qualified students share similar concerns. What’s more interesting is that many of them can also help to answer each other’s questions.

For the past few years I’ve given an annual talk at UCL to students of the HCI with Ergonomics M.Sc. It’s always a pleasure to share my questionable world view with impressionable minds, and I look forward to the sessions in much the same way as one secretly enjoys a visit from a drunken uncle.

In an effort to make this year’s session a little more interactive, I pulled out an old Knowledge Management set piece:

- Distribute post-its

- Ask everyone to write one question they wish they knew the answer to (preferably about the topic at hand).

- Stick the post-its on the walls. (It’s surprising how much people group them, despite your invitation to use any of the three free walls)

- Ask everyone to read each post-it.

- If they too want to find out the answer to a question, tell them to mark the post-it with a question mark. If they think they have an answer, mark it with a tick.

It’s not that surprising to find that a room of similarly qualified students share similar concerns. What’s more interesting is that many of them can also help to answer each other’s questions.

The purpose of this exercise is of course to show that networking and collaborating is valuable, and not just a case of awkward conversation and limp handshakes. However, having made this slightly facile point, I realised that most of the posted questions were damn smart and deserved to be shared more broadly. So here are a few that were particularly interesting, and some proposed answers from myself.

Is the graphic design of a site more important than usability when initially attracting users to the site?

I say yes. Research shows users form an opinion on the credibility of a site within milliseconds of visiting it. To form a valid opinion on usability takes use, which may not happen if those impressions are negative. However, the line between the two is of course blurred, and a site can successfully convey usability through layout, visual design and information hierarchy. There are plenty of other factors that have an impact too: load times, content and proposition spring to mind.

How many hours do you work a week?

Define “work”. I’m paid for 37 hours, and most of that is spent on billable client work. But add in commuting, writing articles and conference talks, mentoring, and reading about my field and it would exceed 60. Yes, I’m aware that’s a little unhealthy. Good thing I enjoy it.

What’s the most useless skill you think we’ll learn from this course?

Probably rifling through academic papers to find an authoritative source that proves or disproves a detailed HCI argument. Truth is, not many people in industry will care. It’s more important to judge the the problem at hand and make the right design decisions based on context. HCI theory can give a strong advantage here, but you’ll need to state your case with something more real: usually how your client will make more money by following your advice.

How much do you get paid?

Not telling. But here are some approximate London figures: £25,000 is fair for a graduate-level position, rising to £35–40,000 with a couple of years of experience. Senior people should be looking at £60,000 and up (seven years and above, probably managerial responsibility). Freelance rates typically range between £275-£400/day.

What are the best design tools in HCI?

Thinking, conversation, sketching, software. In that order.

Can you be a good UX designer and a good programmer at the same time?

You can be good at both, yes. But who wants to be just good? Deep specialists tend to better than jacks-of-all-trades, and only extremely rare superheroes can be world class at both. I do, however, strongly recommend that all designers learn to code to a reasonable standard, and that all developers learn the fundamentals of design. Speaking each other’s language is the easiest way to ensure good designer-developer relationships, and one of the easiest ways to become substantially better at your job in a short time.

Do you need to draw well / be arty to be a user experience designer?

Some drawing talent helps, but sketching well is a skill that can be learned and that comes with practice. Its main value is when communicating with clients – a well-crafted sketch can simply convey more information than a poor one. However, it’s more important to develop a designer’s mindset. As Jason Santa Maria says, “sketchbooks are not about being a good artist, they’re about being a good thinker.”

EuroIA 09 in review

This sense of mutual destiny – two nations connected by a single structure – feels entirely European. EuroIA was similarly interwoven with shared experiences of linguistically awkward networking and untold cultural unity.

It’s important to accrue tactics to cope with the disruption of travelling. Quick currency conversions, self-conscious squints at unfamiliar coins, departure lounge distractions (ask Alain de Botton). In Scandinavia, I’ve learned to open clearly with “Hello” to announce myself as a foreigner, since the local salutation “Hej” is a homophone with informal English equivalents.

Copenhagen, site of EuroIA 2009, and Malmö, where my evening sofa awaited, share more than greetings, efficiency and cost of living. They are joined by the 7.8km Öresund Bridge, a zoetrope giving glimpses of distant wind turbines in the water.

This sense of mutual destiny – two nations connected by a single structure – feels entirely European. EuroIA was similarly interwoven with shared experiences of linguistically awkward networking and untold cultural unity. The sessions ranged from poor to intriguing (I’m still no fan of the blind review process) but there was something of a BarCamp atmosphere of willing each other to succeed. EuroIA is a gathering of the underdogs, feisty and proud, and it doesn’t have to be the way they write it in the States.

I particularly enjoyed Joe Lamantia‘s peek into the architecture of fun, Sylvie Daumal‘s struggle for acceptance in a hostile environment, and Andrea Resmini‘s intricate analysis of how IA can bridge the real and digital worlds. Perhaps it was a shame that these sessions were book-ended by an American keynote and closer. Their sessions were undoubtedly interesting, but I hope to see a European presence in these elevated slots next year.

My talk The Future Of Wayfinding seemed to be well received. The topic fitted well with the conference theme of Beyond Structure. Topics such as the Semantic Web, ubiquitous computing and what I can only clumsily label ‘unhierarchy’ were prevalent, and I fully expect them to be reflected in next spring’s US circuit.

Next year we visit Paris, capital of a country almost entirely oblivious to user experience work. It seems we Europeans really do pull together in the face of a challenge.

dConstruct 09 in review

At its best, the fifth dConstruct was simply outstanding. In its rare low points, it disappointed. As such, it’s at a crossroads.

‘After you build forty or fifty websites there really isn’t any magic in it.’

dConstruct’s comfortable niche as the thinking person’s web conference was quickly disrupted by Adam Greenfield’s early remarks. Decrying web and UX design is a risky strategy in a room made largely of web designers and developers, yet it was a thought entirely consistent with our theme of Designing For Tomorrow. The phrase wrapped topics that have been of recent interest to us Clearlefties: ubicomp, gestural interfaces, networked devices and what lies beyond our familiar digital horizons.

Adam led us into a world where information is omnipresent and persistent, where actions stick to identities and the presentation of self is a largely forgotten luxury. A world where objects become services, shared not owned, implies a post-capitalist swing perhaps alluded to by recent economic events. As a recent and voracious reader of Everyware, I was thrilled by Adam’s talk. I’m sure the imminent podcast will reward careful re-evaluation.

Mike Migurksi provided a practical counterpoint with a case history of Stamen’s information design work, with subsequent colour commentary by Ben Cerveny. Ben’s dense, rapid idea stream was perhaps a step too far after such an analytical opening; although Stamen’s work is undeniably excellent, many felt a gap between the metaphysics and the design output, and some of Ben’s more elaborate statements seemed hard to grasp.

Brian Fling explored the mobile field with characteristic flair and pace. Focusing on the future lives of the post-millenials native to the digital age, Brian proposed that history will judge the mobile (and the iPhone in particular) as the flying car we have been waiting for. We are living through a second industrial revolution, based on the portable, personal power of bringing people closer through technology.

Next up, an elaborate Gaia theory of sci-fi and interaction from Nathan Shedroff and Chris Noessel. In an entertaining presentation, the over-used Minority Report example was only (multi)touched upon once, and Jurassic Park’s ridiculous UNIX scene was rightly used for cheap laughs. Of particular interest was the pair’s evidence that anthropomorphism can exist at non-visual levels (consider R2D2’s bleeps and Amazon 1-click servant), although, like Ben before, some other claims seemed rather hazier.

Robin Hunicke, known for her work on “the Maslow’s Hierarchy game known as The Sims”, unfortunately alienated her audience with a spoiler (albeit well meaning) for a film still on general release, and struggled to recover favour. Her West Coast bubbliness sat awkwardly at odds with her academic subject matter, which was coincidentally recapped by August De Los Reyes. Any Microsoft speaker knows he has an uphill battle to win over a sceptical audience; fortunately August’s self-deprecating humour was an instant hit. We imbue objects with intelligence (slide rules, other technological tools), so why not emotion too? Heartbroken families insist on the repair, not replacement, of their Roombas – can we conjure similarly powerful dynamics in the systems we create? August closed with Office Labs’ concept video, a surprisingly rousing vision that raised hairs on necks across the Dome.

The stage was set for a wonderful denouement from Russell Davies, who produced a performance straight from the traditions of British music hall. Russell predicted that digital buildings will give us “Blade Runner brought to you by the makers of Cillit Bang”, and that as technology matures the only way we will escape cliché is to redomain, appropriating ideas from other fields. Russell provided a marvellous reminder that, despite the intelligent contributions of the day, as an industry we are prone to hubris. We’d be daft to disregard the marvellous infrastructure our media predecessors have created.

At its best, the fifth dConstruct was simply outstanding. In its rare low points, it disappointed. As such, it’s at a crossroads. The trend has certainly been cerebral, and this year’s theme certainly encouraged abstract exploration. Early feedback says our audience is happy with this, and that the differentiation from other conferences is an important part of dConstruct’s appeal. Yet there’s always a danger of vanishing into pretension, and the conference must of course appeal to 700+ attendees.

I’m sure Clearleft won’t be taking any snap decisions. dConstruct has become part of the fabric of our company and hopefully the annual schedule, and, in line with our chosen theme for the year, we’ll be thinking carefully about what happens next. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the day and your preferred direction for dConstruct 2010.

Photos: Matt Biddulph, FriiSpray, Tom Jenkins.

Sweating the small stuff

Outrage. Ikea recently switched corporate typeface, moving from Futura to Verdana across all their marketing, including their printed catalogue and ads.

Outrage. Ikea recently switched corporate typeface, moving from Futura to Verdana across all their marketing, including their printed catalogue and ads.

To typography enthusiasts, this is like Mozart announcing a kazoo concerto. Futura is a type classic, skilfully designed by a master craftsman and demonstrating real artistry. It’s excellent for distinctive identity and brand work – so much so that Ikea had practically made it their own until now.

Verdana was created to act as body text on low resolution computer monitors. And it’s well designed for that purpose, but it doesn’t suit print work or any size above petite. At large sizes it looks plain fugly, with characters that appear juvenile at best. Use of Verdana in this way definitely constitutes bad typography.

The slight is all the greater coming from a company that has, to an extent, brought design into the lives of many people who previously believed it was the domain of turtlenecked pseuds.

Ikea’s reason was ostensibly to ensure consistent use of fonts across web and print platforms, and to ensure global compatibility across all languages. A strange choice, given that Verdana has notable deficiencies in its character set. However, it’s possible that Ikea isn’t as naive as we think. My colleague Paul Lloyd hypothesises that the switch is a deliberate ploy to make the company appear less expensive. It’s an old strategy: cheapen the aesthetic and the perception of price goes down. Plausible, at least.

By all means we can point, laugh and lament the lack of design skill at the company. However, some of the outrage has been ridiculous, particularly since we can never truly know the reasons behind the choice. Hell, there’s even a petition to reverse the change.

I believe that if companies make bad design choices that’s their prerogative. If I worked for Ikea, I would have fought tooth and nail to dissuade them from this choice – but no, I won’t sign a petition. Let them eat cake, and if design is as important as we say it is, the market will prove their mistake.

Herein lies my bemusement at the design community’s reaction. Behind the indignation, does any of us really believe that this typographic gaffe will affect Ikea’s sales? Is it really as egregious an error as we make out? Or are we merely acting out the stereotype designers fight so hard to shake off: the aforementioned turtlenecked pseud complaining that their soup isn’t hot enough?

Typography matters. Used well, it can elevate communication in astonishing ways. But, asAegir points out, there are bigger design challenges facing Ikea and indeed the global manufacturing industry than choice of corporate typeface.

Design is about sweating the big stuff; hopefully even changing the world. Often that involves the small stuff too, but focus solely on the trivia and it’s hard to avoid becoming trivial yourself.

Lessons from UXCampLondon

Since Saturday’s UXCampLondon I’ve been thinking about what I took from the experience.

Since Saturday’s UXCampLondon I’ve been thinking about what I took from the experience.

One

The devil is in the details. With such a discerning audience, we had to offer something well run and as seamless as possible. We succeeded, thanks to accurate estimation of various factors including no shows, time between sessions, budgets, and the apparently inevitable delay caused by a GPS-less taxi driver. This attention to detail was entirely down to the commitment of our wonderful volunteers, upon whom I relied to orchestrate the minutiae. Delegation was my preferred tactic, as noted by Johanna in her closing notes.

Two

You can’t live blog a conference you’re running.

Three

There’s something about user experience designers. We took an early decision that UXCampLondon would be a one-dayer since the field is generally slightly older, more interested in spending a Sunday with their family than slumming it on an office floor. This upset a few purists (“It’s not a BarCamp if you don’t stay over!”) but was indisputably the right choice.

Many people commented that UXCampLondon had a unique atmosphere: enthusiastic, yet mature and urbane compared with the (admittedly enjoyable) rough bluster of most BarCamps. It further convinced me that user experience folk are my people: highly likeable but intelligent and well balanced; opinionated yet open to alternative views.

Four

Free alcohol cures all ills.

Five

The best lessons are often hidden. In some ways, I didn’t get that much from UXCampLondon because my mind was always elsewhere and I attended few sessions. But that overlooks the other benefits I took from the day. In particularly, I got further proof of the growing strength of our community, and further experience in handling difficult situations (we had plenty).

A couple of people have asked if I’m planning a sequel. It’s possible, but not for a while. I’m taking some time off, and I’m sure there are many other people well suited to running UXCampLondon2.

Thanks to our volunteers, our supporters and of course all the attendees for making UXCampLondon a success.

Photos: Rob Enslin and Adam Charnock.

Please start from the beginning

Busy with final UXCampLondon preparations, so light on time to blog. However, I did manage to find 30 min to be interviewed by Ryan Taylor for his “Please start from the beginning” series.

Busy with final UXCampLondon preparations, so light on time to blog. However, I did manage to find 30 min to be interviewed by Ryan Taylor for his “Please start from the beginning” series.

Blank canvas

A blank wall is an invitation to a designer. As soon as the paint dries, I’m sure we’ll drown in post it notes and poorly-taped flipchart sheets. Heated debates will be held at the sharp end of a marker pen.

We’ve been busy. Not only have we taken on ‘leftie number nine, but we’ve also moved into larger studio. Obviously this means higher overheads, which takes careful thought in the middle of a recession, but it also means (amongst other things) we finally have wall space.

A blank wall is an invitation to a designer. As soon as the paint dries, I’m sure we’ll drown in post it notes and poorly-taped flipchart sheets. Heated debates will be held at the sharp end of a marker pen. The war room of my most recent project featured 20’ of whiteboard, which became a great way to sketch and walk through design concepts before stepping into prototyping. Drawing on the walls has thus become a minor fetish. It’s highly visible, and thus brilliantly suited to critique. It keeps you moving and alert, rather than immobile in your chair. And it also has the marvellous appeal of finally being able to do something you never could as a kid.

I hope to to share some of our scribblings in due course.

The angst of the user experience designer

While the web makes it easier for one person to reach millions, it doesn’t make the relationship easier to comprehend.

My work is used by millions.

When the thought first struck the numbers were lower, but I was stunned. I quickly surmised the only way I could retain objectivity and impartiality was to bury this thought, but it wouldn’t leave me alone. I’m hoping that I can now make sense of it by voicing it.

Of course the scale of the web excites me; I’m delighted and humbled that my work can communicate with so many people. Very few roles have such scale. Architecture, perhaps. Journalism. Politics too, although I’m hardly comfortable with that comparison.

While I admit that it’s something of an egocentric thrill, I’m no household name and nor do I wish to be. Web design is far less important than, say, teaching or healthcare. What matters more to me is that I do great work, and having a large canvas provides me with fascinating ways to achieve this.

However, while the web makes it easier for one person to reach millions, it doesn’t make the relationship easier to comprehend. My excitement is tempered by vertiginous apprehension. From these millions, there will be thousands who love my work. There will also be thousands who hate it: people who relied on the old site, who appreciated a section I removed, whose needs I’ve overlooked in the hurry to get the job done.

With such scale, these users are anonymous to me, just as I am to them. While I work hard to understand them and design to support their needs, there’s no way I can know I’ve improved things for an individual user. I hope I’ve done right by them.

The angst of the user experience designer.

UX London in review

There are things we want to improve for next year (I’m particularly keen to involve a greater diversity of speakers), but we think the important stuff was more or less right. We hope others agree.

What a week. Turning thirty is an event on its own, without the hard work of running and speaking at a major conference. However, either despite or because of the stress, UX London was a fantastic experience and one I can’t wait to repeat. Due to hurried tweaking of my slides I missed several workshops, so here’s a rundown of the opening day.

The talks

Opener Peter Merholz implored us to expand our mandate from digital user experience to other touchpoints across the entire customer experience. This shift towards service design requires a patient collaborative and strategic approach, familiar from recent ‘getting a seat at the table’ discussions.

Many design-led companies are blessed with a visionary, customer-focused CEO: think Disney, Apple, Southwest. Leadership begets culture. Culture begets user-centred service. Those of us who lack such a figurehead can kick-start a design culture by espousing a clear set of design principles – a topic that arose numerous times. We must also encourage others to see design as more than aesthetics and stereotypes. Instead, design should be an activity: a means of getting ideas out of people, and of honing those ideas until they are useful to customers.

Eric Reiss revealed that Brits are now the angriest people in Europe, and clearly wanted to emulate our success. In a continuation of the service design theme, he poured scorn uponWine.com, eBay and that easiest of targets: airlines. By illuminating the theory and history of customer service, Eric also pointed out how easily we are ruled by complacency. A company can have 90% satisfaction with no discernable increase in loyalty. 83% is nothing to be precious about.

Quoting liberally from Matthew Frederick’s increasingly popular 101 Things I Learned In Architecture School, Luke Wroblewski explored the Yahoo! homepage redesign by way of the parti, a site’s central concept stated in the language of design.

Pointing to parti’s “non-architectural” derivation (market factors, resources, company strategy), Luke led us through the quagmire of 10,000 stakeholders and 590 million users. In the midst of the politics, parti remained a sanity check for UI components – “do they bring us closer to our concept?” – an elegant way to avoid the religious and political debates with which we are all so familiar.

Dan Saffer channelled Dreyfuss in his new talk, proselytising the benefits of behaviour as a major competitive advantage, both more appealing and harder to replicate than me-too featuritis. Since the interface is the product, we should look beyond form (we’re looking at you, Motorola RAZR) and focus on motivations, expectations and actions. Our behavioural system needs close attention to the details of feedback and transitions, coupled with a laser-like focus on the product’s key function or ‘Buddha Nature’.

Carefully appointed to the graveyard shift after lunch, Jared Spool‘s brand of humour had the desired effect. When not regaling us with tales of incompetence and poor process (his workshop later yielded the classic “You can always look at what your competitors are doing. That way you’ll always be a step behind them!”), Jared focused on intuition. As did Don Norman later, Jared sung the praises of complexity, where users have sufficient knowledge to embrace it. A design is intuitive if the gap between user knowledge and target knowledge is small; therefore we can improve our designs by increasing the former and reducing the latter. A powerfully simple message cloaked in trademark wit.

Jeff Veen covered ground previously trodden by Tufte, but was at his most interesting revealing some of the design decisions involved in the development of Google Analytics. Skilfully sidestepping the inevitable Doug Bowman question from the audience, Jeff gave a fascinating insight into the design process at the Googleplex. It turns out that a t-shirt reading “Math is easy, design is hard” does not go down well on the campus.

Even amid this array of talent, Don Norman was still for many the main attraction. I was lucky enough to sit opposite Don at the previous evening’s speakers’ dinner and found him to be a genial, quietly spoken man with a ferocity of opinion unsurprising to any reader of his classic books. Opening philosophically (“It is now time for questions…”), Don made the case for complexity in a deeply intelligent and observant address. Tesler’s Conservation of Complexity means a certain level of complexity can never be eliminated, merely shifted around a system. We shouldn’t fear this. Without complexity we become bored. Without complexity we wouldn’t have music and games. Therefore, seek simplicity but distrust it.

We were, of course, treated to an analysis of everyday things including light switches and, yes, doors. But the graphical user interface came in for the most critical insight. Norman believes that we are approaching a point at which the GUI is no longer scalable (consider trawling through icons of 15,000 photos on your hard drive). No doubt bringing a smile to Google’s face, Don believes search will become the dominant paradigm of the next age of UI.

Further thoughts

While the level was deliberately high to act as balance to the practical workshops that followed, I left with some conflicting thoughts. Monday’s talks were excellent, expansive, and expansionist. It’s important that we understand the context of design, but I firmly believe we must balance strategic interest with staying true to our own Buddha Nature: designing stuff. While there are occasions to broaden our scope, we should be mindful of diluting our message through landgrab. Our biggest mistake would be to believe our own hype too much; we are still seen as web designers, not saviours of the corporate world. We must prove our value if we are to be valued.

I also question our use of examples. As is typical of a UX conference, examples of what not to do abound. They’re a pure form of entertainment: funny and flattering to those in on the joke. However, there’s benefit in talking about good examples too – yet our portfolio is wearing sadly thin. Tivo (never popular in the UK), ClearRX and the ubiquitous iPod can only take us so far, and I hope we can soon talk about other successful examples of user experience design. If we can’t find any, perhaps we aren’t as effective as we hope?

However, these are all minor thoughts lingering after what I think was an excellent opening for our new conference. There are things we want to improve for next year (I’m particularly keen to involve a greater diversity of speakers), but we think the important stuff was more or less right. We hope others agree.

To close, an anecdote from Dan at White October. At the beginning of Leisa Reichelt‘s workshop, it appears she asked her audience to introduce and tag themselves, in the traditional BarCamp way. The most common tag? “Inspired”.

May links

In the absence of sufficient time to finish my drafts, some interesting reading

In the absence of sufficient time to finish my drafts, some interesting reading:

- The Dice-O-Matic — guy runs games server. Players complain of pseudo-random number generation. Guy builds gigantic dice rolling machine, capable of 1.3 million rolls a day.

- Burnout — new A List Apart article by Scott Boms. “Know thyself, but be gentle.”

- The Maturity Gap — thoughts on nurturing new UX talent.

- Please Say Something — wonderful animated short from the creator of Octocat.

- The ultimate ways to test your site — the official version of my previously-published article for .net. I didn’t choose the title.

- Caring For Your Introvert — a paean to the quiet underclass.

- Examining Game Pace: How Single-Player Levels Tick — fascinating analysis of pace and flow within game design.

I wouldn’t have got round to reading many of these if it weren’t for the marvellous Instapaper iPhone app, which I highly recommend. Having my to-read backlog to accompany my daily commute has been a godsend. More thoughts on the commute later.

Announcing UXCampLondon

Just a quick note for anyone who’s not heard: UXCampLondon will take place on Saturday 22 August at the Gumtree offices in London.

Just a quick note for anyone who’s not heard: UXCampLondon will take place on Saturday 22 August at the Gumtree offices in London.

For anyone unfamiliar with the BarCamp model, it’s a grass-roots ‘unconference’ born from the desire for people to share and learn in an open environment. All attendees give a talk, demo or some kind of session, and all are treated equally. No headliners, no product pitches, just a friendly (if intense) event focused on sharing and socialising as well as learning new stuff.

Although I’ll talk about it occasionally on this blog, most info will end up on the website (to be announced), the wiki page and on the UXCampLondon Twitter account. More info, including a website and ticket details, will be announced in the next few weeks.

Following up

I am not writing off the UK user experience scene. Far from it. I see UX as my calling, not just my career, and I’ll work as hard as I can to help it thrive here. And we are clearly on an exciting upward swing.

In a previous life I juggled a role that was equal parts information architecture and knowledge management. The fields are closer than you may think, both revolving around codifying, transferring and assimilating information.

Knowledge managers strive for the ‘watercooler moment’, where a colleague mentions in passing something that saves you weeks of work. There’s plenty of thought on how to engender this culture – even interior design has a role – but it can only ever come about by getting people talking. Sometimes, particularly in a fledgling community, this can be achieved via a social object.

My post last week (“Complex inferiority – user experience in the UK”) certainly generated the discussion I hoped for, with opinion split on whether I had a valid point and even whether my points were helpful or harmful. To that end it served its purpose, but I would like to clarify a couple of points.

I am not writing off the UK user experience scene. Far from it. I see UX as my calling, not just my career, and I’ll work as hard as I can to help it thrive here. And we are clearly on an exciting upward swing. However, I’m convinced that we need to be honest about where we must improve, and until we have (amongst other things) widespread mentoring, closer ties between academia and industry, more vocal discussion and a body of excellent work I will always see room for improvement.

Let me also be clear that I don’t advocate empty self-promotion. We don’t need rockstars. We need excellent people contributing to the community. My definition of a leader is someone who goes first, and encourages others to follow. Obviously I hope to contribute in whatever small way I can, but I urge anyone who cares about this scene to take the reins and try out new things to help our nascent community.