Complex inferiority: user experience in the UK

I think it’s time to examine why the UK hasn’t made its mark in user experience.

It’s a time of reflection in our field. However, as the drama unfolds on the mailing lists, I’ve been thinking closer to home.

Clearleft committed to UX London knowing that it would be the first major user experience conference on British soil. To an extent this made the decision easier, and gave us confidence that we’d meet our two main goals: first, to stimulate a buzz about user experience in the country and second, to create a profitable and worthwhile conference. That said, our predictions were conservative, particularly once the economy hit training budgets, and we expected steady sales right up until the event.

To sell out four months early was a wild surprise. The reason for this success (inasmuch as an event yet to take place can be called successful) is undoubtedly the calibre of speakers we’ve attracted. We targeted those acknowledged as pioneers of the field, through a simple selection process of debating, budgeting and arguing.

We soon realised that most speakers on our rapidly-expanding fantasy list were from the US. The chance to see luminaries from across the pond is a strong selling point for the conference, but I for one was disheartened that there weren’t stronger contenders based in the UK.

After all, Brits are major players in the web world. We’re the second most represented nation (10.8%) in the A List Apart survey, and in other areas of web design – particularly standards – we’ve built a strong community of practitioners and leaders, many of whom I’m lucky to know and work with.

I think it’s time to examine why the UK hasn’t made its mark in user experience.

Whither the rockstars?

Let me first explain that I hate the “rockstar” label. I use it only as an accepted term for someone widely admired who inspires others to success. Although the UK has some excellent practitioners, none has the profile or level of respect that, say, Messrs Norman, Merholz or Spool enjoy.

I recently posed a question on a couple of local forums: “Who is an inspiration in our field?”. It seemed innocuous enough and elicited interesting responses, but I must confess an ulterior motive. Totting up the nationalities of the names proposed quickly dispelled my concerns that I was merely projecting personal bias:

It seems safe to say that even we don’t see our community as a centre of user experience excellence.

It is hard to disagree. I consider the canon of UX literature and can barely think of a notable British author. Even online we’ve never produced an article with the impact of ia/recon, The Cognitive Style of Powerpoint or even The $300 Million Button.

Yet our practitioners are plentiful; just watch the steady stream of job ads and recruiter phonecalls. The London IA group has grown to nearly 500 members. Fifty people regularly dedicate their spare time to UX Book Club. Yet none of us has made a lasting mark on the field.

Perhaps it’s not rockstars we need. After all, it was only last month that JJG admonished the user experience field for celebrating those famous for talk, not action. So let’s look at that action. Can we find world class user experience work on these fair shores?

Our work

Happily, I think isolated pockets of excellent UX work exist: moo.com, the impressive new graze.com, and many national news organsations can all hold their heads high. However, if we examine some of Britain’s best-known dotcom successes – let’s say Lastminute, Betfair, last.fm, Gumtree, confused.com – none is by any means a paragon of user-centred design, although some are improving.

I am also struck by the level of our community discussion. We seem stuck in the domain of tactics: deliverables, Visio vs. Omnigraffle, “are there studies that prove x?” This is the bread and butter of UX, necessary but not sufficient, and I’m surprised at how few people are aiming higher. For all its infuriating problems, the IxDA list is full of discussion that truly stretches the limits of our environment: UX as design activity, getting a seat at the strategy table, the future of interaction. It seems these issues aren’t yet being taken seriously in Britain, which I believe greatly limits our scope to take user experience to the next level.

Education and mentoring

Although it’s a truism to say that education doesn’t meet the needs of the technology market, Britain has few post-graduate courses that adequately prepare students for a career in user experience.

Our best-known Masters courses include UCL’s HCI and Ergonomics, the RCA’s Design Interactions, and City University’s Human-Centred Systems. I’ve interviewed, spoken with and befriended many graduates from these programmes, and have even spoken a couple of times at UCL. My conclusion is that although these courses have some praiseworthy elements, British higher education seems stuck in the mindset of human-computer interaction. Think CHI papers, Jakob Nielsen, eyetracking; interesting stuff for sure, but of little relevance to practitioners. Only the RCA is perhaps an exception, although by some reports it too has fanciful flaws.

We need universities to offer practical design tutelage alongside the important theory. Ideally, education should be challenging industry at its own game and contributing directly to today’s practice. In the US, this is becoming a reality. CMU’s Interaction Design Masters is highly regarded, with alumni including Dan Saffer. New York’s School of Visual Arts has kicked off an MFA Interaction Design with a fantastic roster of industry talent.SCAD runs an Industrial Design Masters with a healthy Interaction Design component.

Although educational protocols are different in the US, it is nonetheless notable how so many American HE courses have such strong links with industry and leading-edge practice. We are far behind, and many British students are left struggling to catch up in their first role.

Our higher education needs to change its focus towards practical design, not Jakob andCHI papers. Responsibility for this lies not just with university staff. As practitioners, we need to take an interest in the activities of our educational system. It creates the future of our profession, and we cannot afford to abdicate our responsibility to help new entrants thrive.

We must also look at the needs of those who don’t or can’t take the formal route. Mentoring is an important way for our young field to grow, yet the IA Institute’s mentoring scheme lists just four mentors in the UK, compared to 49 in the US. It’s disappointing that there aren’t more people offering this kind of support, since many new UX designers need guidance and reassurance that in an emergent field like ours we are all to some extent learning it as we go.

Job market and culture

The vast majority of British user experience jobs are based in London, a notoriously fragmented city. There are few other British cities with the critical mass to sustain a community, so it’s essential that the capital has an active scene if the national community is to take off. Yet for years it lay dormant, with only the occasional UPA event to keep things ticking over. Fortunately this is changing, and I hope London can soon serve as a community example for other cities.

Britain also faces subtle issues around the culture of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial aspiration and startup rates are measurably lower than in the US. Although I have no data to confirm this, I suspect that user experience designers in Britain tend to work in larger companies where their influence may be limited. Certainly there have been few high-growth British startups with a strong UX focus, and despite the country’s strong design heritage, 43% of Britain’s businesses don’t invest in design at all.

Personality

Finally, I believe there’s a personal angle. The self-deprecating British nature and user experience designers’ tendencies toward thoughtful introversion means this is never going to be a group eager to shout from the rooftops. However, it is time for us to ignore the shackles of cultural norms and become more comfortable with minor self-aggrandisation. We won’t get far unless we share confidence in our work, our values and our worth to business, and to do this we need to become more vocal. No one will talk about our successes but us.

A silver lining

I’m sure there are causes beyond these infrastructural deficiencies. However, the combined effect has helped to create what until recently I described as an anaemic British user experience community.

Fortunately things are changing, and I’ve grown increasingly excited at the stirrings we’re showing. We’re starting to come together socially, and are organising new events to share what we’ve learned. The recent IA Mini conference and this summer’s UXCampLondon are important grass-roots continuations of this. UX London will hopefully cause some related get-togethers, and I’m also encouraged to hear that the UPA is looking to engage further with the community.

This activity is all to be welcomed, so long as we coordinate these efforts to avoid the harmful divisions currently seen in the US. It’s important to recognise those involved in setting up, attending and talking about these events, but we can’t leave it to a few. We need others to get involved and suggest new ways to foster our community.

The future of British UX

We’re finally showing some great momentum, and we desperately need to sustain it. To this end, we need community, and we need leaders. Not rockstars, but people who can help to spearhead the user experience movement in this country. In short, we need to get Britain talking about UX if we want the UX field to be talking about Britain.

We need to be visible and vocal. We need people to share their work and their thoughts. To debate, organise, write and present. We need more people to step forward both to organise events and act as mentors. We need to foster grass-roots activity and encourage cross-pollination. Designers across the country should mix, swap war stories and become friends. Practitioners and academia should be discussing how we can be more useful to each other.

After so long in the nest, it’s time our community took wings.

IA Summit 09 – days 2 and 3

The adversarial mood, no doubt exacerbated by economics, meant that the majority of off-stage discussion focused on the politics. However, it was mercifully balanced with a determination to unify and move on.

Maybe we’re finally getting back at all those cheerleaders.

The closing comments of Eric Reiss’s session A house divided summed up the IA Summit’s descent into angst, self-doubt and jealousy.

The tenth year of the Summit saw our field struggling with the onset of puberty. We’re stumbling towards an adult identity, while battling the conflicting voices amongst our ranks. It won’t be pretty but, like puberty, the necessary transformation will take us to new maturity.

But first, the content. Conference highlight Karl Fast used analogies from Tetris to describe usability testing. Studies show that skilled players over-rotate blocks to get a feel for how their shape will integrate with the current board. Yet classical usability theory would regard this as inefficient. How do we discriminate between errors and this epistemic action?

Fast also gave an overview of embodied cognition. In short, Descartes was wrong. Cognition is not just in the head; we also use our bodies to help shape our thoughts. This new theory of cognition presents problems. Our tactics, metaphors and patterns have been set up for a mind and body isolated. A finger here, an eyeball there. Mice, keyboards, touchscreens. None reflect the monism of embodied cognition.

Miles Rochford discussed the under-reported issues of IA for the rest of the world. It was a fascinating and sobering session that, like Fast’s, showed us how far we still have to go. Fred Beecher and Jared Spool also gave popular talks, but the Saturday focus was Eric’s. In this notorious session, he mixed mild personal censure with more welcome criticism of the IxDA’s divisive tribalism and the cult of ego over community. Applause and anger from the audience, which was probably the desired effect.

A similar sentiment was picked up by Jesse James Garrett in his closing plenary, in which he sounded the overdue death knell of division by job title. The information architect and the interaction designer are no more: we are all user experience designers, and we always have been. Amen.

JJG also called us out on our flimsy cult of celebrity. We have practitioners famous for what they say, rather than what they do. What great works of user experience have there been? Who made them? How have they made a difference? It’s a polemic that will surely go down as an important turning point for our profession. Every practising information architectuser experience designer should listen to it at the soonest opportunity.

The adversarial mood, no doubt exacerbated by economics, meant that the majority of off-stage discussion focused on the politics. However, it was mercifully balanced with a determination to unify and move on.

I’ve little interest in the petty politics of job titles, of IA Institute versus IxDA. However, I do care strongly about our combined future. It’s natural and healthy to air and resolve these conflicts rather than pretend there’s nothing wrong. Indeed, I see it as a mark of our growing maturity. But we must unify. In times of weakness, we need the strength of numbers, and this can only come from reversing the entropic breakdowns we’ve seen in recent years. Indeed, at the Sunday night meal there was a grass-roots movement to rename the conference (“The Memphis signatories”?) to simply The Summit, to reflect our new common agenda. Whether it works is to be seen, but I agree we need to change and broaden our focus if we are to find our true place in the world.

IA Summit 09 – day 1

It’s just one day, but it’s been fascinating and I’m sensing the stirrings of a breakthrough. Perhaps the pendulum of specialisation is swinging back, and the days of arguing over job titles and definitions can soon be dropped in favour of discussing what we have in common, and how we can all be better.

Seriously, 8.30am for a keynote? Not easy, particularly for those still getting used to Central Standard Time.

Michael Wesch‘s “Mediated Cultures” started laboriously, making points we’re all hopefully familiar with by now: changing media changes relationships, and so on. To quote the disillusioned Generation Y-er Wesch frequently referenced, “Whatever”. However, he soon livened up as we dived headlong into his preferred territory: internet counter-culture. Any keynote featuring 4chan’s Pedobear has to be deemed pretty interesting, and a welcome tone of openness and iconoclasm was set for all.

These themes have continued throughout the day. There does seem to be a genuine willingness here to tackle the issues and neuroses of the IA community, and perhaps even to overcome some of the divisons that we’ve so carefully constructed over the last few years. Whisper it quietly, but some even posited that, you know what, IA has been design all along. Eric Reiss’s session “RoI: Speaking the Language of Business” broke through some of the voodoo economics our forefathers* have been passing off for years, and implored us instead to sell the value of our services. The conclusion – focus on close, trusted relationships rather than mythical dollar values – seems dangerously close to that employed by design consultancies for generations. Similarly, Donna Spencer‘s Design Games session was pithy and direct, skillfully ignoring any nervous questions of process (“Why design games?” “What’s the deliverable?”).

Other sessions were patchy, as is to be expected of a blind review process, but the breaktime discussions as ever proved to be the really valuable moments. It’s been fantastic to connect with some very smart people, and I hope to continue in the same vein tonight and throughout the weekend.

It’s just one day, but it’s been fascinating and I’m sensing the stirrings of a breakthrough. Perhaps the pendulum of specialisation is swinging back, and the days of arguing over job titles and definitions can soon be dropped in favour of discussing what we have in common, and how we can all be better.

*Well, Jakob.

At the IA Summit

After six years, I’ve finally made it over to the Information Architecture Summit. This year it’s Memphis, and again it’s drawn an exciting group of people whose names (but not faces) are so familiar to me from all those articles, mailing lists and Twitter streams.

After six years, I’ve finally made it over to the Information Architecture Summit. This year it’s Memphis, and again it’s drawn an exciting group of people whose names (but not faces) are so familiar to me from all those articles, mailing lists and Twitter streams. Of course I’m here to learn from them, but I’m also here to network. As local UX types may know, I’m frustrated with the coy nature of the British scene and am hoping to pick up some tips on how we can raise our profile.

As the conference proper starts tomorrow, today was mostly set aside for settling in and meeting people. Inevitably, this included a group trip to Graceland, 8 miles down the road. Graceland is everything you’d expect: garish, crassly commercial, yet strangely intriguing. Part of the fun is analysing whether the lack of taste on display is representative of Elvis or merely the decade that dominates the property.

I’m hoping to give a daily wrap-up once we’re underway (liveblogging is too much like work, I’m afraid). If there’s sufficient demand, I might look into a quick “IA Summit recap” session back home for those unable to make it

Architecture of the stadium

This post is clearly an excuse for me to indulge a slight stadium fetish; however, I do think they provide great examples for how our identities, attitudes and actions can be shaped by the built environment. A branding exercise writ large in brick, if you will

People are often surprised to hear I’m a devoted football fan and Cardiff City supporter. Perhaps it doesn’t gel well with people’s perceptions of me (whatever those may be); however, I find football gives me an exciting break from daily concerns, and a chance to be part of the tribal culture inherent within us all. It’s a way to feel friendship with total strangers, an outlet for anger, joy and happiness, and an opportunity to mix with a wider cross-section of people than my limited horizons otherwise offer.

I also have a huge love for the stadiums and they remain one of the reasons I prefer to follow Cardiff at away games.

Stadium architecture has a clear effect on the physical presence of the club and atmosphere at games. The psychological effects on fans, referees and players are well-documented, but home advantage is also believed to give a genuine physical edge, hypothesised to be caused by testosterone increases in players. This effect is especially strong in defenders and goalkeepers, for whom the battle is particularly territorial.

Stadiums must also have logistics and facilities for up to 80,000 visitors (around the population of Shrewsbury), hundreds of police, stewards and officials, media and players. The range of requirements is pretty astonishing.

Clubs are known by the reputation of their grounds and the atmosphere they inspire. Some teams are known for poor support and quiet games (the “prawn sandwich“ brigade). Cardiff, on the other hand, have a reputation as a very intimidating club. There are many reasons for this: passionate fans, unfortunate hooliganism, and the constant battle to be noticed against Wales’ supposed national sport of rugby. However, the stadium plays a huge part too.

Ninian Park is a classic ‘old style’ stadium, well beyond its useful life yet still possessing the hallmarks of bygone eras: terracing, woeful facilities, and some intangible ‘character’. High among Cardiff fans’ many concerns for the future is the worry that atmosphere and indeed a piece of the club’s identity will be lost as we move into our new stadium (at top) in May.

On my travels with Cardiff I’ve been to some dismal grounds, and loved them all (a foggy January week night in Mansfield where you couldn’t even see the other end of the pitch comes to mind). Below, Watford’s stadium: ugly and an easy target for ridicule, but possessing far more character than many other grounds I’ve visited.

And then there’s always the rare occasion when your team performs and suddenly you find yourselves part of something huge:

This is my best shot from last year’s FA Cup Final, which Cardiff pretty much fluked our way into. Wembley is of course enormous, and again the atmosphere is shaped by the architecture. Expensive facilities and location make for expensive tickets. This (and the sponsorship derived from TV coverage) means money spare for banners, flags and other paraphenalia. Huge crowds make for huge expectations, high ceremony and lengthy big build-ups, but they also make co-ordinating singing impossible. Many Cardiff fans said they didn’t get the same sense of atmosphere as at a traditional away game, since the noisiest fans were spread across the ground rather than, as is common, concentrated in a group.

The nosebleed-inducing height also changes one’s experience of the match. From here you can see the sweep of the game, like a general, but not the blood and sweat of the touchline.

This post is clearly an excuse for me to indulge a slight stadium fetish; however, I do think they provide great examples for how our identities, attitudes and actions can be shaped by the built environment. A branding exercise writ large in brick, if you will.

Review: Sketching User Experiences

I found Sketching User Experiences to be an intelligent, far-reaching book that expanded my horizons but also left me somewhat frustrated.

As did many cities, London chose Bill Buxton’s Sketching User Experiences as the subject of the inaugural UX Book Club. I kicked off the discussion with my take on the book, and have hence decided to transform my notes into a written review for the benefit of anyone not present.

I found Sketching User Experiences to be an intelligent, far-reaching book that expanded my horizons but also left me somewhat frustrated. Buxton uses an inverted pyramid style, beginning broad and narrowing as he goes. This splits the book into what I felt were three sections (although Buxton himself declares only two parts: Design as Dreamcatcher andStories of Methods and Madness).

The first section, an analysis of the role of design, innovation and its business ecosystem, is to my mind the strongest. The ubiquitous iPod example surfaces early, but Buxton finds a way to inject this familiar narrative with fresh interest, by focusing on design strategy, acquisitions versus innovation, and the fundamental need for companies to create new stuff (faintly reminiscent of Marty Neumaier’s Zag). Buxton also elegantly dispels the myth that we cannot predict the future, demonstrating by historical example that supposedly new technologies typically have a minimum twenty year adoption curve.

The book then narrows to a discussion of process, asserting that “sketching is the one common action of designers”. I initially struggled with this definition, feeling it focused too much on visual output rather than our cognitive process. However, it soon becomes clear that Buxton isn’t interested so much in the sketch as artefact, but in sketching as an activity and a gerund. This culminates in his strongest chapter Clarity is not always the path to enlightenment which describes how sketching acts as a social object; the product of thought but also the catalyst for fresh ideas.

Sadly, from here, the book’s relevance declines. Examples and methods illustrated towards the end, while interesting, are clearly academic in their origin. As such, they may be fine for an M.A. project but, despite protestations of low overheads, they aren’t suitable for the fixed budgets and quick turnaround of agency user experience design. The latter sections are therefore at their best when they focus on simpler techniques. Chapters on tracing and photographs to as aids to sketching, and a convincing chapter on storytelling stand out.

I also remain unconvinced by the book’s overall stance. Buxton is a wonderfully knowledgeable author but his strong opinions often make Sketching User Experiences a paean to what I see as elitist practice. Big design up-front is regularly reinforced as the only worthwhile approach:

“Jumping in and immediately starting to build the product… is almost guaranteed to produce a mediocre product in which there is little innovation or market differentiation” (p141)

As a known Agile sympathiser, I have had Sketching User Experiences used as a weapon against me (“that’s not how Buxton says we do it”) and I found this narrow view hard to reconcile with my personal design ideology.

There are also small doses of intellectual arrogance that diminish the book’s impact. At the end of an unrealistic chapter on physical prototyping, Buxton asserts that any qualified interaction designer should be able to replicate this example in under thirty minutes. It’s a claim that begs the question of whether Buxton, or indeed anyone, has earned the right to impose their view of interaction design upon our community. The net result is that, although the book certainly helps designers, I’m not sure it helps the cause of design.

These ideological quibbles aside, I do recommend Sketching User Experiences. It was a strong choice for a book club and provided some good discussion points. It has also motivated me to draw more, to buy new Moleskines, improve the visibility of my sketching and sketches, focus on stories as important design tools, and to watch The Wizard Of Oz (you’ll see).

The making of Tourdust

A few weeks ago, a new travel startup called Tourdust quietly slipped into public release. It was my first major project for Clearleft, so I’d like to explain a little about the design process, challenges and decisions involved in its development.

A few weeks ago, a new travel startup called Tourdust quietly slipped into public release. It was my first major project for Clearleft, so I’d like to explain a little about the design process, challenges and decisions involved in its development.

Information architecture

The Tourdust proposition is a classic exploration of the long tail: linking offbeat, authentic tour experiences with travel geeks across the world. Think olive oil tours or bear watching, not package deals; a shared platform for small operations that may not even have websites of their own.

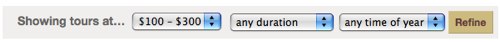

Since the site intends to house thousands of travel experiences, IA was a primary concern from the outset.Holidays involve a broad information space, with extensive metadata: duration, location, activity, organiser, price, availability, cost, and so on. Slicing through this data could be a daunting challenge for users, so an early task was to focus on how people understand and find travel experiences.

After design research, personas, scenarios and considerable thought, we concluded that the two critical factors in choosing an ‘active’ holiday (as opposed to a week sunbathing) werewhat the activity is and where it happens. It’s therefore no accident that these two variables are featured prominently on the site, as both navigation and headings. For a while, I even pressed (gently) for the site to be called everythingineverywhere.com.

Navigation

Since what and where operate independently of each other, they lend themselves well to faceted navigation. However, many faceted systems aren’t good at conveying their function, so we made the decision to split these two key variables off and turn them into primary navigation by means of dual nav bars, part breadcrumb and part hierarchical menu.

The other metadata is mostly taken care of by a “refine bar”. I believe it’s far better to show many results (particularly so in the early days when product numbers are low) and allow the user to trim the scope, than to create a bulky and elaborate “advanced search” feature that could confuse and easily return no results.

Unusual controls like these can be a risk; they’ll only be successful if users understand what they do, and how. The designer has to quickly suggest and demonstrate their operation through affordance and example. The affordance is largely visual: arrows, 3d overlap, and the behaviour of the menus as new options are selected. Demonstration by example occurs when a product is selected, possibly off the homepage. The dual nav is updated to show the intersection of activity and location (eg. “Cycling in Germany”), quickly establishing an understanding of how the controls work independently.

Of course, since these were uncommon controls, the proof was in the user testing. Paper prototypes were the order of the day here, mostly for budgetary reasons. Had more time been available we would have undoubtedly created HTML prototypes using Polypage to be watertight in our conclusions. However, they tested well for an unusual UI element and we felt confident this approach would allow for simple yet powerful navigation through this complex array of products.

Visual language

Another factor we agreed early on is that visual impact plays a huge role in the travel industry (not a massive leap of imagination, given the glossy large photographs seen in printed brochures). It was therefore very important for us to make the products as visually exciting as possible.

My early sketches involved very large, widescreen photos, and this detail was carried all the way into the final product. The widescreen format allows for some great detail of landscapes and panoramas, without the vertical overhead.

It also involves some tricky cropping mechanics. Most cameras take pictures with a 4×3 ratio (landscape) or 3×4 (portrait). The site halves the short side and instead uses an 8×3 ratio. Therefore, when a user—in this case, a tour operator—uploads an image, the system prompts them to crop the photo to show the top, middle or bottom half (the Maths is more complex for portrait shots). This cropping is initially done by clever CSS, repositioning the image vertically behind the 8×3 slot. Once a choice is made, the crop is made server-side for improved performance.

Process

We designed and built Tourdust as an Agile project, in collaboration with our Rails dev partners, New Bamboo. I’ve discussed the challenges of Agile design on A List Apart, but I believe that despite a few teething problems mid-project (mostly a cause of us not allowing enough lead time for design), the site is better than we could have created under waterfall methods.

In particular, since the clients were still exploring the business space whilst the site was being built, the business model changed halfway through development. With waterfall, this would have been beyond the point of no return, but with Agile’s flexibility we were able to accommodate the new requirements with only modest difficulty.

We also found ourselves fulfilling a strategic role as well as just designing the site experience. Frequently this involved reaching into the realms of service design, advising on features, functionality and proposition. One of the outcomes of this liaison was that great swathes of functionality were cut en route. “Worry about it when you need to worry about it” became a useful answer for many scalability questions. I think taking these bold decisions gives Tourdust more focus and a better user experience.

Endgame

Lest I paint too glowing a picture, the site isn’t perfect. Had we had more time, there are dozens of tweaks we’d have made. Imperfection is usually a tricky proposition for designers, particularly so at Clearleft: we do believe the devil is in the details, and our work is usually subjected to high scrutiny. Despite this, we’re proud of what was achieved on a modest budget, and hope we’ve given Anna and Ben the best platform to make Tourdust a success.

Of course, it’s a potentially difficult time to launch a startup. The recession is likely to dent the high-end, luxury travel market, meaning the site’s primary focus is currently on local, UK-based tours. But I do think, if the range is broad enough to gain traction, Tourdust can emerge on the other side in a strong position. I also couldn’t think of better people to take on this challenge than Anna and Ben. People who’ve put everything on the line to follow their dream are an inspiration, and it was a pleasure working with them. They’re true travel geeks and I think their confidence and love for the field will stand them in great stead.

Of course, it’s also down to the users, so I’d encourage you to have a play and I’d love to hear any comments you have about the site.

Why “best practice” must die

Anyone who’s worked in the web is aware of the “best practice” cult. To me, it’s a lazy creed that exhorts us to switch off and plunder others’ work, and the time has come to rebel.

Anyone who’s worked in the web is aware of the “best practice” cult. To me, it’s a lazy creed that exhorts us to switch off and plunder others’ work, and the time has come to rebel.

Firstly, there’s the pure language involved. “Best” implies something that cannot be improved upon. A world of best practice gives us creationism, chariots, and gramophones. It negates progress.

There’s also a more sinister side, which is when it’s wheeled out as an argument in design projects that are heading off the rails:

“Ah, but that’s not how eBay do it”.

The unspoken implication is that eBay know better than I, and therefore I should defer to their wisdom. It’s an argument that I find misguided more than insulting. “That’s not how eBay do it” is industrial, corporate thinking, entirely irrelevant to the 21st century. For the truth is that large companies often don’t have a clue about design. One’s skill and knowledge are entirely independent of the size of your employer: I’m confident I know as much about my profession as the employees at any large company.

The best practice trump card also fails because it doesn’t understand the nature of practical design. It’s not a transferable commodity: you can’t just screw a design solution into place. Good design must be appropriate and relevant to the particular problem. The factors involved—technological, strategic, sociological—are far too complex and variable for a plug and play approach. To say “Well, a dropdown worked here…” is to ignore factors that can actually work in your favour. A company that rejects the easy route and takes the time to understand technology, strategy and users can offer designs that makes it stand out from the rest.

I’m not advocating isolating oneself from the surrounding environment. For instance, at Clearleft, we regularly perform competitor analysis at the start of a project. It’s useful to see where others’ strengths and weaknesses lie, and helps us understand the landscape. However, not once has it given me the answer to a design problem. That always comes later, with thought, with detail, and after many failed attempts.

So let’s not allow the enforced limitation and unvoiced threats of “best practice” to pollute our thinking. It’s harder work, sure, but standing out and being better always is.

The h1 debate

Warning: There follows an arcane debate about HTML semantics, which will be extremely tedious to some.

Warning: There follows an arcane debate about HTML semantics, which will be extremely tedious to some.

Today has seen a minor revival of one the web’s perennial debates: whether the site header or page header is the most important. Its trivial intractability is perhaps only exceeded by the old UI chestnut of whether positive confirmation buttons should go on the left or right (think OK/Cancel versus Prev/Next). Frankly, it matters little, but I can’t sleep and I’m not one to miss out on a nuanced semantic debate.

Right now, you’re on my site Ineffable, reading a post The h1 debate. So which is the most important header on the page? Whichever is chosen should be marked up as <h1> (the HTML for the topmost header) for reasons of search engine optimisation, clean code, and so on.

The case for the site header

A purist might say that semantically and logically the site’s name is the primary tier. This would mean the hierarchy for this paragraph is: Ineffable > The h1 debate > The case for the site header.

While perhaps correct from an ontological perspective (a site has many articles, with many sub-sections), this has the drawback that the <h1> is the same for every page on the site. This is bad for search engines and may make orientation more different for those using screen readers. I also have a more fundamental concern, namely that this imposes a model that matches the designer’s understanding, but not the user’s.

The case for the page title

Pedantry is often important when it comes to good markup, but here I believe pragmatism must win out. This pragmatism arises when looking at the problem from the user’s perspective.

A user arriving at the site may indeed want to orientate themselves by seeing the name of the site, but their main goal is to find relevant information. This is particularly the case if they’ve come via a search engine, wherein they entered text of interest to them and leapt straight into the article itself.

The most important thing to a user is therefore what the page is about. This topic is far more likely to be represented by its title than the site name, and it’s logical that this title should be marked up as the <h1>.

My chosen hierarchy for this section is therefore The h1 debate > The case for the page title, with Ineffable possibly coming in as an <h3>. Note that, while an <h3> may be a subsection of <h2>, this isn’t demanded by the spec; and I think this is the right solution for this particular site.

This said, the answer may be that design classic “it depends” – with contributory factors including the size of the site, its purpose, and user behaviour. Particularly for small sites where users frequently navigate from the homepage down, I could see a site name <h1> being appropriate, while large sites with lots of ‘deep link’ traffic would be better suited by a page title <h1>.

Coping with a mainstream Twitter

The practical upshot is plenty of new users, including several of my real-life friends. While it’s great to have them on Twitter, I have my own selfish concern: will I be able to cope?

January was the month that Twitter lurched towards the British mainstream. Stats show an astronomical rise in site and search traffic, and the rich and famous are now falling over themselves to connect with their fawning public.

One may ask why this tipping point has happened first in the UK, rather than the States or elsewhere. One possible explanation is that a small number of influential celebrity types have hastened this outcome, and it’d be easy to fall into a daft sociocultural analysis of Britain the country and Britain the network. Stephen Fry as the powerful Gladwellian connector, uniting the geeks and the unwashed, previously so suspicious of each other!

My money’s on random chance. The initial conditions were set, after which chaos theory is the dominant force (yes, perhaps I have been listening to Jeremy too much).

The practical upshot is plenty of new users, including several of my real-life friends. They’re perhaps still on the early adopter side of mainstream but they’re not the type to, for instance, write blog posts about why people are joining Twitter. While it’s great to have them on Twitter, I have my own selfish concern: will I be able to cope?

I’ve previously mentioned that I have an approximate following threshold of 250. My workload and lifestyle enforce that personal limit, and I can’t realistically keep up to date with more people. So if my less geeky friends continue to join, whom do I drop? The model’s different from Facebook, where I can simply accumulate “friends” (a virtual notch on the bedpost) and then largely ignore them. So do I drop existing Twitterers, many whom I’ve never met but still give me a wealth of inspiration and knowledge, or friends whom I miss and am always eager to hear from? Ambient intimacy or friendship?

It’s a quandary. I’ve been trying to convince friends to join Twitter for a long time and it would be an irony if, once they join, I admit I don’t want to follow them. Yet I’m already operating a one-in-one-out policy, and something will have to give. My likely approach will be to take a much more relaxed and liberal approach to unfollowing people. Just as I’ll go and talk to various people at a party, so my attention will shift around a bit online. It’s either that or I face a cacophony in which I can hear no one.

However, I’m aware that people have very different attitudes to being unfollowed, so I’ll treat this post as a prophylactic excuse. Seriously, it’s not you, it’s me.

Can we avoid redesign backlash?

Your best strategy is to sweeten the deal with desirable functionality and an interface that matches users’ current mental models; if you don’t have those, batten down those hatches and prepare yourself for retaliation.

Users hate redesigns, or so we’re told. To be fair, the evidence does seem to support the argument: the last year or so has given us some clear examples of user backlash.

- Facebook: Right now, the largest anti-redesign group has 1,656,258 members. I’m with them in spirit: I think the Facebook redesign is weak, although it happens to suit my particular needs well (i.e. a lifestreaming service for non-geeks).

- last.fm: A site I dearly love, but whose redesign did little to address its IA problems, while introducing a gap-toothed NME-meets-Facebook visual direction that does it few favours. I wasn’t alone in my disappointment; there were quickly over 2,000 comments (warning: link may choke up your browser), often wildly negative.

- News sites: The Guardian, FT.com, and the BBC also transformed themselves within the last year, with ‘robust’ opinion voiced on each. News sites also have to handle the added complexity of politics: even if the Beeb were to find a cure for cancer, there would still be someone complaining it’s a waste of his licence fee.

All of these redesigns followed the familiar backlash pattern. To begin, post on your blog that you’re rolling out the redesign, and explain your rationale. Bonus points for words such as “widgets” and “personalised”. Having lit the touch paper, retire to a safe distance as the Kübler-Ross hatefest commences:

- Denial: “Why on earth did you change it?”, “The site was fine the way it was”

- Anger: “My twelve-year-old could have done better!”, “F—- you, I’ll never use this site again”

- Bargaining: “At least give us the option to use the old version…”

- Depression: “I used to love this site. Now I can’t bring myself to use it.”, “I miss [feature X] :(”

- Acceptance: “Actually, I’ve been using it for two weeks now and…”

The accepted wisdom on the cause of this backlash is that users learn how to navigate the site and achieve their goals, only for these strategies to prove useless in a redesign. Something akin to the way we learn the layout of a supermarket and optimise our routes accordingly.

I don’t buy this argument. Navigation may have a minor impact but users are notoriously good at satisficing—finding a good enough option—in unfamiliar waters. Instead, I think the reaction has a psychological basis. A favourite site has an emotional connection for us: we like it, it likes us, and we can depend each other. We fear the disruption of that equilibrium: a redesign raises the question of whether the site will grow in a direction we don’t want to follow. As Hugh MacLeod says in How To Be Creative:

Your friends may love you, but they don’t want you to change. If you change, then their dynamic with you also changes. They like things the way they are, that’s how they love you – the way you are, not the way you may become.Ergo, they have no incentive to see you change. And they will be resistant to anything that catalyzes it.

So, following from my earlier post, why has the New Xbox Experience (NXE) been so successful where other major redesigns have failed? Remember that this is Microsoft, a company not afforded the grace period that, say, Apple or Nintendo are.

My first thought is that the NXE is another good example of the MAYA principle in action. In particular, the quick interface, a cutdown version of the dashboard launched from within games, is structurally very similar to the old UI. I don’t know much about the NXE’s design process (although if anyone has any links I’d love to read them), but certainly it’s easy to imagine usability tests showing this was a welcomed feature.

The new UI also didn’t push boundaries particularly far, since in some areas it was simply catching up. The real value came not in the interface but in service innovation, incorporating new and desirable functionality (Netflix, HD installation) as a key part of the new design.

Compare this with Facebook’s lurch towards lifestreaming, which is at odds with the popular model of the site and therefore unlikely to appeal to many users. The public’s opinion seems to be that Facebook is a place to get in touch with people, rather than see what they’re up to. It could be argued that as friendship saturation reaches 100% (i.e. you have no friends left to add), lifestreaming becomes more useful. So perhaps Facebook are ahead of the anticipated user curve, but I doubt the 1,656,258 care.

We must also consider the fundamental question of whether a major redesign is wise idea in the first place. Jared Spool, for instance, argued long ago that big relaunches are dead. To a large extent I agree, and there are usually alternatives; for example, the classic eBay redesign story, which I assumed to be apocryphal but have been assured by insiders is true.

In a nutshell, a meaningless background was removed from a seller page. Pandemonium. After strong resistance the background was reinstated, to everyone’s satisfaction. In fact, the rebellious users were so placated that they failed to notice the designers slowly adjusting the background’s hex values over the next few months. The background got lighter and lighter until one day—pop!—it was gone.

To return to my initial question, I think it’s a brave and lucky company that can find a way to redesign without creating unrest amongst a large userbase. Your best strategy is to sweeten the deal with desirable functionality and an interface that matches users’ current mental models; if you don’t have those, batten down those hatches and prepare yourself for retaliation.

New Xbox Experience

The NXE is an attempt to catch up, so the changes aren’t huge, but it’s interesting to see how they affect the overall console experience.

Yesterday the ‘New Xbox Experience’ (NXE) upgrade was finally rolled out to all Xbox Live users. The old system (created by AKQA and known as the “blades”) was more dated than bad, but the market has shifted during its five-year lifespan. Online is now the default platform for many, casual gaming is the new black, and the previously masculine bias of the games industry has softened substantially in recent years. The NXE is an attempt to catch up, so the changes aren’t huge, but it’s interesting to see how they affect the overall console experience.

The avatar

Yes, that’s me. We can see the avatar as the natural extension of the Xbox gamertag, created back in 2003. Personification is the trend: game companies are keen to give players flexibility to define an identity for themselves online. Certainly a name alone no longer cuts it. It’s worth remembering that Xbox Live controversially remains a chargeable service, so there is a clear impetus to at least equalise with competitor online services, the Wii being the obvious parallel.

Rare, the avatar designers, say they were keen to find the balance between toylike and overly realistic (there’s that uncanny valley again), but I think the result is bland: approachable, but far too close to Nintendo’s territory and too limiting to create anything with real character.

However, the new avatars do have a couple of interesting features. A friend’s status is now reflected by their avatar’s pose (eg. asleep = offline) and apparently avatars will be embedded in small games in future. Microsoft have, in essence, created a hook around which gaming experiences can hang, which is a smart move.

Functionality

There are some minor functional changes, probably the most significant of which is that you can now install games to the hard drive and run them from that. Not only is this long overdue, given that it’s been standard practice on PCs for 20+ years, but it also tackles one of the 360’s major flaws: its extremely noisy DVD drive. It also allows for faster switching between games, which will suit those players who like to throw tantrums when they start losing.

There’s also the new ability to ask your Xbox to download items remotely, although this does of course rely on you leaving it on all the time.

Interface and IA

The interface itself isn’t much changed, except that the blades have become panels and adopted the increasingly-clichéd Cover Flow stance. More usefully, there’s a welcome tightening up of the IA, which means hours wasted fishing around in Settings should be a thing of the past.

Migration

The detail I’ve been most impressed by was the migration experience itself. Upgrades are one of the areas where just a little user focus can have a huge impact: compare firmware upgrades for the iPhone with most older handsets. The entire upgrade took just four minutes (excellent for what is essentially an entire OS upgrade), with seamless plug-and-play operation and an explanatory video upon relaunch.

Reaction

Somehow, we’ve reached the age where a firmware upgrade for a console can create a buzz—almost universally, people seem to love the NXE. The really interesting question is why, which I’ll write a followup post about shortly.

Personally, I’m not as glowing as others. I actually quite liked the old Xbox personality: hardcore over casual, masculine over feminine. This update softens that stance, and I think it’s a mistake to drift towards Wii territory. Minor gripes aside, it is an undeniably well-crafted piece of work, tackling known problems, creating extensibility and, most importantly, getting people talking about a rather old console in the lucrative run-up to Christmas.

Farewell to anti-intellectualism?

My personal hope for Obama’s presidency is the end (or, at worst, the long suspension) of a culture of anti-intellectualism that has plagued Western politics for years.

Until recently, I equated politics with duty: something that I must participate in, but that was never elevated above a choice between deeply unsatisfactory options.

I find most politics ideologically empty, and it is almost a truism to say that we know very little about how President Obama will govern. However, I do believe that yesterday’s election will make a profound difference to the world, and for the first time I’m genuinely excited at the prospect of political change. Of course the race issue is important, but my personal hope for Obama’s presidency is the end (or, at worst, the long suspension) of a culture of anti-intellectualism that has plagued Western politics for years.

Anti-intellectualism is not a uniquely right-wing stance, but it has been used with alarming regularity by the current US administration. Bush himself is the archetypal example but, consigning him to the history he deserves to inhabit, we’ve seen examples in the recent campaign too. Sarah Palin’s attempt to champion the cause of the “real America”, by conflating intellect and elitism, failed profoundly.

The right’s attack has not been constrained purely to intelligence: it has also involved the devaluation of education, reason and evidence. All have been systematically discarded by the incumbent government, state education boards, Supreme Court Justices and hawkish military generals.

This framing of intellectuals as The Other is counter-productive, dangerous, and hopefully moribund.

It is clear that Obama is an acutely intelligent man and a gifted orator. As such, he received his mandate from two ends of the spectrum: those with the lowest and highest privileges. His race and his stance on welfare made him attractive to disenfranchised minorities, while his sharp, rational demeanour made him almost entirely dominant amongst liberal urbanites. This top-and-bottom split was complemented by a generational shift: a fierce reaction against the hegemony of old, rich, white men. The campaign itself owes much of its success to the internet and, yes, even graphic design. Fairey’s Hope poster will stay with us as one of the most important political design works of our generation.

Republicans may wish to blame their loss on the economy. 63% of Americans say it was the primary issue. But I think the Republican attitude that the economy needs to be restored to its former glories is fundamentally wrong. It doesn’t. The way forward is a new, sustainable, evenhanded economy with environmental conscience, and checks and balances protecting the public purse from the risks of the free market. Where the poor get richer, not just the rich.

While I’m concerned I’ve compromised my cynicism and have gone a bit gooey over a single politician, yesterday feels to me as significant as 9/11, and as constructive as the aforementioned was destructive. I believe that, given the pace of innovation and change in our society, we are already caught up in a second Renaissance. Politics, historically, always lags behind social trends. Yesterday it caught up, and the 21st century can really begin

Why is technology so dull?

So let’s imagine an operating system that sees you’ve split up with your girlfriend and says sorry. A program that knows you were out drinking last night and therefore uses muted colours and suggests you take frequent breaks. A mobile that loves going on rollercoasters.

The concept of personality has us hooked; just look at Cosmo quizzes and the thousands of online personality tests. And rightly so: it’s something that has profound effects on our friendships, love lives (that old “she’s got a nice personality” chestnut) and careers. For instance, Bruce Tognazzini claims that designers must have an ‘N’ in their MBTI, one of the slightly less dubious profiling tools. (I actually agree with him on this. I’m an INTJmyself.)

However, we’re also a little infatuated with personality, and often assume that someone’s actions are caused by the ‘type’ of person they are, while ignoring the social and environmental forces that influence them (the fundamental attribution error). In reality, personality is always framed and affected by the world around us, meaning behaviour can be quite variable. Just because someone’s angry once, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re an angry person. We have to work backwards, interpolating someone’s underlying personality from several observations of their behaviour. You can’t really get to know someone from a minute in their company.

For instance, at a football match, I drink, swear, and slip into a latent Welsh accent. This is no surprise—my environment almost demands it of me, since I’m surrounded by drunken, sweary Welshmen. But you’ll find me behave very differently in bed with a girl, going through airport security, or talking to my Nan. This behavioural variance is part of being human and people who lack it are deemed to be boring. If you behave the same in a nightclub as in a library, you won’t be invited out again.

Constrast this with technology, which behaves in a very rigid manner—the same in all environments. I think it’s time to make technology more interesting by introducing some mild behavioural variance. Sampled over a few readings, we can then start to form an opinion about the underlying personality, which is where we make those emotional connections.

Clearly we can’t go too far. Some behavioural consistency is essential for usability, and some devices are better suited to quirkiness than others. However, the dead zero we’re at now is clinical and drab.

Fortunately, we have the jigsaw pieces we need to imbue technology with personality. We just need to put them together. As mentioned above, behavioural variance generally comes from environmental influence. This meshes nicely with technology’s increasing context-awareness. Bluetooth, RFID, APIs, accelerometers, spimes etc, common geek parlance, all refer to ways technology is becoming more aware of itself, other technologies and us. But it doesn’t need to be this esoteric. Glade recently released a quite silly air freshener that only activates in the presence of a human.

The concept of an emotional response to technology isn’t new, by any means. For example, the uncanny valley. I happen to be sceptical of the uncanny valley idea (no real reason), but I challenge anyone to watch the following and not be slightly saddened:

So let’s imagine an operating system that sees you’ve split up with your girlfriend and says sorry. A program that knows you were out drinking last night and therefore uses muted colours and suggests you take frequent breaks. A mobile that loves going on rollercoasters.

This could be so much more fun. And the exciting part is I don’t think it’s too far out of our reach—for starters, we already give out plenty of these informational cues (knowingly or not):

Ultimately what we’re aiming for is intelligence (or at least pretence thereof) in technology. In the words of Piaget, “intelligence is the ability of an organism to adapt to a change”. I think behavioural variance is a perfect example of this adaptation, and for that reason I think we shouldn’t be scared of giving our future technology a personality of its own.

Based on my lightning talk “A rainy day, lost luggage and tangled Christmas tree lights” given at Skillswap On Speed, 29 Oct

Printing press workshop

Technology has made our outputs so much quicker and more reliable, but without the hard work, patience and dedication of centuries of craftsmen we would be far, far behind.

A slightly shortened week, since Clearleft took Monday off for a day of printing press revelry at Ditchling Museum. Ditchling was, for many years, the home of sculptor, typographer and unspeakable pervert Eric Gill, and a large proportion of the museum is therefore dedicated to his work.

The first half of the day was dedicated to examining the museum’s collection and creating our own original works inspired by it.

I contented myself with the (terrifyingly precious) first edition of Gill’s Cantica Natalia, and was quickly absorbed in transcribing it and noting down the unusual trills and marks that aren’t represented in modern notation. My rather sketchy original work was a worms-eye map of a seaside town using only these odd musical ligatures from the score. Slightly Klee-esque, without the talent.

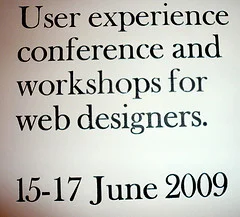

In the afternoon we got our hands extremely dirty playing with the Stanhope press. Jeremy and, who else, Richard probably got the best from it, setting the following plug for UX London in 60pt Baskerville:

My efforts were less successful, but I did manage to print a new header for this blog, which I will at least try to integrate over the next couple of weeks.

It was, of course, very refreshing to spend some time out of the office and learning more about the foundations of our industry. The other point I took from the day was a renewed sense of humility. Technology has made our outputs so much quicker and more reliable, but without the hard work, patience and dedication of centuries of craftsmen we would be far, far behind.

The survival of web apps

I’ll admit it: I’m a little scared. I was too late for the bursting of the first bubble; every year I’ve spent in the industry has been one of growth. A potentially contracting market is a new thing for me.

I’ve had a busy time of late, in particular thanks to a couple of days in Switzerland and Austria, followed by the Future Of Web Apps (FOWA) conference in the Docklands.FOWA’s a little large for my tastes, but it’s undeniably well organised. Three sessions stood out (the uniformly excellent Gavin Bell, Benjamin Huh’s history of Icanhascheezburgerand Kathy Sierra being her enthusiastic self) but my particular interest, and one I’d love to have heard more about, is in the eponymous future bit.

I’ve been thinking for a while about how our field will develop and while I believe mobile, the Cloud and the Semantic Web are going to be big factors, I’ll park them for future posts and talk about the clearest issue on our horizon: the economic downturn.

Truly this was FOWA’s cri de coeur. A majority of sessions made mention of it, and Sun’s Tim Bray scrapped his keynote at the last minute to deliver Get through the tough times – which, although somewhat cataclysmic, is definitely worth 30 minutes of your time. Over a matter of days, the economy has become the dominant topic of the web. Dan Saffer askswhat designers can do to help (in short, make stuff). Khoi Vinh cautions us to be careful about our data. Andy Budd talks about how to survive a global recession.

I’ll admit it: I’m a little scared. I was too late for the bursting of the first bubble; every year I’ve spent in the industry has been one of growth. A potentially contracting market is a new thing for me.

Of course, self-correction is a fundamental part of the system we live in. Boom precedes bust. And I’m confident there’ll always be work for smart people at the top of their game. To paraphrase Naomi Klein, if capitalism has one strength, it’s that it has a knack of creating new jobs to replace those that are lost.

But our environment will undoubtedly change. Andy makes the point that it’s now even more important for businesses to understand their customers; after all, retention is far cheaper than acquisition. He’s right, but unfortunately I think few will accept the perceived risk: tight budgets make waterfall, big requirements and long research phases a thing of the past, if they weren’t already. UX designers in particular might find it hard to be relevant in these short-term times. To survive, we have to become more agile (both lower-case and upper-case ‘a’) and demonstrate our value from day one. Quick, practical research. Quick, volatile design. I’m currently writing an article on how we can do this; but, looking beyond survival tactics, is there still room for user experience to make a difference strategically?

Perhaps, if we make the case clear. Now is a particularly bad time to compete solely on features – the cost is of that arms race is simply too high. I forsee UX people increasingly filling the role of strategic chaperone, dragging businesses away from unsuitable functionality and focusing them on the core product. Cash-strapped businesses are already going to build just half a product; we have to help them focus on the right half.

I also think lower levels of capital will catalyse a far deeper trend: the end of the website as destination. Once upon a time, creating a brochureware site or, recently, another social networking app was a viable strategy – there was market share to be gained, and there was capital available. ‘Me too’ sites captured their share of eyeballs, CPA and other such meaningless trivia. These days are gone, and if this is your future model, the question will be one of survival, not expansion.

Historically, companies that thrive in recessions aren’t those that drive efficiency and cut costs: they’re those who can execute on an idea that changes everything. So the next phase of the web, now upon us, will see it evolve as an enabler, not a medium. The real value now is in getting devices talking, connecting products and services, and synthesising information in new, valuable ways. Services like Dopplr are already halfway there: so laden with APIs and interconnectedness that they exist as intermediaries – a ‘social physics engine’, to use Matt Biddulph’s wonderful phrase – the site itself is largely redundant. All that counts is the value that it brings to people’s lives.

The good news is this is still very much dependent on a user experience focus – it’s just a different flavour of UX. It’s less about making fractional sales improvements or reducing numbers of customer service interventions. Our role now has to be more about trying to make a genuine difference to the world through innovation. This is noble and, as I said earlier, scary. Change always is, and it’s appropriate that we remain alert in difficult times. But, for good people, the sky isn’t falling quite yet.

The MAYA principle

The adult public’s taste is not necessarily ready to accept the logical solutions to their requirements if the solution implies too vast a departure from what they have been conditioned into accepting as the norm.

One of the benefits of following smart people on Twitter is that I regularly pick up on techniques and principles I’ve not heard of. I don’t remember who first mentioned theMAYA Principle, but I investigated and found a powerful idea I think is worth sharing.

MAYA, Most Advanced Yet Acceptable, is a heuristic coined by Raymond Loewy, who explains it thus:

The adult public’s taste is not necessarily ready to accept the logical solutions to their requirements if the solution implies too vast a departure from what they have been conditioned into accepting as the norm.

What Loewy is saying is that a local maximum exists for creative work: the behaviour, understanding and mental models of our userbase anchor us and cause work that’s too far removed to fail.

Matthew Dent’s recent Royal Mint coin designs are a great example of the MAYA Principle in practice.

The task of redesigning currency is daunting. British coins hadn’t changed since 1968, and as such represented a great deal of tradition and cultural identity. Over the years, we’ve literally come to accept the portcullis, three feathers, thistle, lion, double rose and Britannia as icons of our nationality.

Individually, Dent’s new coins are unashamedly modern. They feature aggressive cropping and striking full bleed layout, with the 5p being a particularly bold example. Britannia they aren’t. However, taken as a holistic whole, the full suite of coins form the royal shield of arms. The design makes admirable use of the concept of closure, whereby our minds fill in the gaps to maintain a coherent pattern. The coins are also wonderfully tactile and interactive: the process of arranging them, jigsaw-like, to reproduce the bigger picture is novel and enjoyable.

Both the common historical thread and the design’s interactive nature were a conscious choice:

I can imagine people playing with them, having them on a tabletop and enjoying them… I felt it was important to have a theme running through from one to another. – Matthew Dent, in The Times

While a traditionalist may not appreciate the individual coin treatment, the strong nod to British history should placate him. The designs also encourage us to reexamine these everyday objects as a result of their interactivity, causing us to refocus on our money, the patterns they display and the connection to our identity they inevitably form. In short, this redesign skilfully mixes the old and the new in a way that is advanced, yet acceptable, to a potentially intransigent public.

Escalation

More and more, I find myself less interested in what web designers have to say.

More and more, I find myself less interested in what web designers have to say.

That’s not to say that there aren’t some very clever people out there – hell, I’m lucky enough to work with some of them. However, I’m worried that as a community we are blinded by our self-importance. Proudly we don the mantles of digital pioneers and imperiously believe we’re the first to encounter the problems we face. How do we make things that people enjoy? How can we help people to share and learn from each other? Can new technologies alleviate social ills? The more I learn about other fields, the more I find that bright minds have been tackling identical problems for years, and the less surprised I am by this discovery.

I’ve reached a stage of my career where I learn more about user experience from outside the field than in. My non-fiction reading list, previously full of every reputable web/UX design book I could devour, now bulges with architecture, Tufte, typography and semiotics.

Most of the intelligent, ambitious web people I know seem to be undergoing a similar escalation of interests. Whether I can count myself as one of them is moot, but I do know that I’m increasingly skipping RSS feeds that talk about web methods, techniques and tricks. I spend my conference budget on inspiration, not tuition, and endeavour to aim equally high when I’m fortunate enough to present to others.

The UX mailing lists, a barometric aggregate of the field’s current interests, seem to be moving upmarket too. Discussions about design thinking are in the ascendency; those about the location of confirmation buttons are bottoming out. Despite the occasional futile game of Defining The Damn Thing, the trend is increasingly highbrow and diverse.

Below, an example of some advice I’ve recently found particularly enlightening:

“Engineers tend to be concerned with physical things in and of themselves. Architects are more directly concerned with the human interface with physical things.”

“Being non-specific in an effort to appeal to everyone usually results in reaching no one.”

Crystalline, and applicable to all design fields. These quotes, as of course you guessed, are not from a web design book. Instead, they are two of many useful aphorisms from 101 things I learned in architecture school by Matthew Frederick – and yet are still more a commentary on design process than advice on a specific discipline.

In similar circles, I’ve recently been inspired by Stewart Brand’s marvellous documentary How Buildings Learn, the companion to the elusive book of the same name. The first episode alone has so many parallels with web design that we ought to be ashamed at how we’ve not drunk more deeply from a well some thousands of years older than our own.

There is, of course, an exquisite irony in a web designer harping on about the questionable wisdom of web designers (particularly when opening with such a shambolic oxymoron). I do think the industry has a great deal to offer its devotees, and there’s still a place for learning from our experts (and I’m looking forward to UX London hugely for this reason), but I do think our community would benefit from removing the blinkers every now and then. Forming a human pyramid is no match for standing on the shoulders of giants.

What if the design gods forsake us?

To this day, I haven’t a clue about the cause; yes, I could have run some usability tests but for a lone image it would have been pure self-placating overkill.

In some design Utopia, everything would be tested. An unseen army of usability specialists would verify everything and free our minds from worrying about unforeseen outcomes. Our users would be empowered, our messages would hit home, our harps would be perfectly tuned, and our gins and tonic perfectly mixed (lime, not lemon, thank you).

Until that day, we’re stuck with the real world, in which designers sometimes have to trust instinct and speculation rather than proof. We try to insure ourselves against getting things totally wrong; to wit, an arsenal of design fundamentals. Mapping. Affordance. Redundancy. Theories with impressive German names. We’ve spent time reading the books, listening to others and forming our own intuitive principles from practical observation. This helps us sleep at night. We’re professionals, dammit.

In a previous job, I ran a new graphical element on our site. The theory was watertight: better visual weight, higher legibility, stronger typography, aesthetically harmonious. A no-brainer. Yet it failed. Horribly. After causing a noticeable dip on conversion (most of e-commerce UX design is predicated on increasing sales), we quickly conceded defeat and rolled it back.

It was embarrassing, needless to say. Whilst not staking my career on this design, I’d taken the time to argue its merits, explaining to the powers that be that although some of them disliked it visually, it was the right solution for many reasons.

This story, to me, explains a significant problem with designing by metrics. You get rapid feedback on whether an approach works, but none whatsoever on why. Sure enough, when we reverted to the ‘weaker’ version, normal service was resumed. To this day, I haven’t a clue about the cause; yes, I could have run some usability tests but for a lone image it would have been pure self-placating overkill.

So, when the design gods forsake us, where do we turn? Obviously, we need rapid feedback. A poorly-received design can be measured in many ways – in this case a simple conversion metric, but in other instances it might surface as reduced clickthroughs, backchannel mutterings, failed usability tests or customer complaints. Remaining alert will depend greatly on our relationship with other parts of the business and the market itself. We also deserve the occasional reminder that user experience design is a subjective matter. Theory is valuable and useful, but the outside world has an uncanny habit of regularly throwing us off our ivory towers. Perhaps this is no bad thing.

That’s why, on reflection, I’m glad this episode happened, despite the hurt pride. Doing what I do wouldn’t be nearly as fun if things worked every time. Who wants to work in a field reducible to process, heuristics and how-tos?