Lessons from UXCampLondon

Since Saturday’s UXCampLondon I’ve been thinking about what I took from the experience.

Since Saturday’s UXCampLondon I’ve been thinking about what I took from the experience.

One

The devil is in the details. With such a discerning audience, we had to offer something well run and as seamless as possible. We succeeded, thanks to accurate estimation of various factors including no shows, time between sessions, budgets, and the apparently inevitable delay caused by a GPS-less taxi driver. This attention to detail was entirely down to the commitment of our wonderful volunteers, upon whom I relied to orchestrate the minutiae. Delegation was my preferred tactic, as noted by Johanna in her closing notes.

Two

You can’t live blog a conference you’re running.

Three

There’s something about user experience designers. We took an early decision that UXCampLondon would be a one-dayer since the field is generally slightly older, more interested in spending a Sunday with their family than slumming it on an office floor. This upset a few purists (“It’s not a BarCamp if you don’t stay over!”) but was indisputably the right choice.

Many people commented that UXCampLondon had a unique atmosphere: enthusiastic, yet mature and urbane compared with the (admittedly enjoyable) rough bluster of most BarCamps. It further convinced me that user experience folk are my people: highly likeable but intelligent and well balanced; opinionated yet open to alternative views.

Four

Free alcohol cures all ills.

Five

The best lessons are often hidden. In some ways, I didn’t get that much from UXCampLondon because my mind was always elsewhere and I attended few sessions. But that overlooks the other benefits I took from the day. In particularly, I got further proof of the growing strength of our community, and further experience in handling difficult situations (we had plenty).

A couple of people have asked if I’m planning a sequel. It’s possible, but not for a while. I’m taking some time off, and I’m sure there are many other people well suited to running UXCampLondon2.

Thanks to our volunteers, our supporters and of course all the attendees for making UXCampLondon a success.

Photos: Rob Enslin and Adam Charnock.

Please start from the beginning

Busy with final UXCampLondon preparations, so light on time to blog. However, I did manage to find 30 min to be interviewed by Ryan Taylor for his “Please start from the beginning” series.

Busy with final UXCampLondon preparations, so light on time to blog. However, I did manage to find 30 min to be interviewed by Ryan Taylor for his “Please start from the beginning” series.

Blank canvas

A blank wall is an invitation to a designer. As soon as the paint dries, I’m sure we’ll drown in post it notes and poorly-taped flipchart sheets. Heated debates will be held at the sharp end of a marker pen.

We’ve been busy. Not only have we taken on ‘leftie number nine, but we’ve also moved into larger studio. Obviously this means higher overheads, which takes careful thought in the middle of a recession, but it also means (amongst other things) we finally have wall space.

A blank wall is an invitation to a designer. As soon as the paint dries, I’m sure we’ll drown in post it notes and poorly-taped flipchart sheets. Heated debates will be held at the sharp end of a marker pen. The war room of my most recent project featured 20’ of whiteboard, which became a great way to sketch and walk through design concepts before stepping into prototyping. Drawing on the walls has thus become a minor fetish. It’s highly visible, and thus brilliantly suited to critique. It keeps you moving and alert, rather than immobile in your chair. And it also has the marvellous appeal of finally being able to do something you never could as a kid.

I hope to to share some of our scribblings in due course.

The angst of the user experience designer

While the web makes it easier for one person to reach millions, it doesn’t make the relationship easier to comprehend.

My work is used by millions.

When the thought first struck the numbers were lower, but I was stunned. I quickly surmised the only way I could retain objectivity and impartiality was to bury this thought, but it wouldn’t leave me alone. I’m hoping that I can now make sense of it by voicing it.

Of course the scale of the web excites me; I’m delighted and humbled that my work can communicate with so many people. Very few roles have such scale. Architecture, perhaps. Journalism. Politics too, although I’m hardly comfortable with that comparison.

While I admit that it’s something of an egocentric thrill, I’m no household name and nor do I wish to be. Web design is far less important than, say, teaching or healthcare. What matters more to me is that I do great work, and having a large canvas provides me with fascinating ways to achieve this.

However, while the web makes it easier for one person to reach millions, it doesn’t make the relationship easier to comprehend. My excitement is tempered by vertiginous apprehension. From these millions, there will be thousands who love my work. There will also be thousands who hate it: people who relied on the old site, who appreciated a section I removed, whose needs I’ve overlooked in the hurry to get the job done.

With such scale, these users are anonymous to me, just as I am to them. While I work hard to understand them and design to support their needs, there’s no way I can know I’ve improved things for an individual user. I hope I’ve done right by them.

The angst of the user experience designer.

UX London in review

There are things we want to improve for next year (I’m particularly keen to involve a greater diversity of speakers), but we think the important stuff was more or less right. We hope others agree.

What a week. Turning thirty is an event on its own, without the hard work of running and speaking at a major conference. However, either despite or because of the stress, UX London was a fantastic experience and one I can’t wait to repeat. Due to hurried tweaking of my slides I missed several workshops, so here’s a rundown of the opening day.

The talks

Opener Peter Merholz implored us to expand our mandate from digital user experience to other touchpoints across the entire customer experience. This shift towards service design requires a patient collaborative and strategic approach, familiar from recent ‘getting a seat at the table’ discussions.

Many design-led companies are blessed with a visionary, customer-focused CEO: think Disney, Apple, Southwest. Leadership begets culture. Culture begets user-centred service. Those of us who lack such a figurehead can kick-start a design culture by espousing a clear set of design principles – a topic that arose numerous times. We must also encourage others to see design as more than aesthetics and stereotypes. Instead, design should be an activity: a means of getting ideas out of people, and of honing those ideas until they are useful to customers.

Eric Reiss revealed that Brits are now the angriest people in Europe, and clearly wanted to emulate our success. In a continuation of the service design theme, he poured scorn uponWine.com, eBay and that easiest of targets: airlines. By illuminating the theory and history of customer service, Eric also pointed out how easily we are ruled by complacency. A company can have 90% satisfaction with no discernable increase in loyalty. 83% is nothing to be precious about.

Quoting liberally from Matthew Frederick’s increasingly popular 101 Things I Learned In Architecture School, Luke Wroblewski explored the Yahoo! homepage redesign by way of the parti, a site’s central concept stated in the language of design.

Pointing to parti’s “non-architectural” derivation (market factors, resources, company strategy), Luke led us through the quagmire of 10,000 stakeholders and 590 million users. In the midst of the politics, parti remained a sanity check for UI components – “do they bring us closer to our concept?” – an elegant way to avoid the religious and political debates with which we are all so familiar.

Dan Saffer channelled Dreyfuss in his new talk, proselytising the benefits of behaviour as a major competitive advantage, both more appealing and harder to replicate than me-too featuritis. Since the interface is the product, we should look beyond form (we’re looking at you, Motorola RAZR) and focus on motivations, expectations and actions. Our behavioural system needs close attention to the details of feedback and transitions, coupled with a laser-like focus on the product’s key function or ‘Buddha Nature’.

Carefully appointed to the graveyard shift after lunch, Jared Spool‘s brand of humour had the desired effect. When not regaling us with tales of incompetence and poor process (his workshop later yielded the classic “You can always look at what your competitors are doing. That way you’ll always be a step behind them!”), Jared focused on intuition. As did Don Norman later, Jared sung the praises of complexity, where users have sufficient knowledge to embrace it. A design is intuitive if the gap between user knowledge and target knowledge is small; therefore we can improve our designs by increasing the former and reducing the latter. A powerfully simple message cloaked in trademark wit.

Jeff Veen covered ground previously trodden by Tufte, but was at his most interesting revealing some of the design decisions involved in the development of Google Analytics. Skilfully sidestepping the inevitable Doug Bowman question from the audience, Jeff gave a fascinating insight into the design process at the Googleplex. It turns out that a t-shirt reading “Math is easy, design is hard” does not go down well on the campus.

Even amid this array of talent, Don Norman was still for many the main attraction. I was lucky enough to sit opposite Don at the previous evening’s speakers’ dinner and found him to be a genial, quietly spoken man with a ferocity of opinion unsurprising to any reader of his classic books. Opening philosophically (“It is now time for questions…”), Don made the case for complexity in a deeply intelligent and observant address. Tesler’s Conservation of Complexity means a certain level of complexity can never be eliminated, merely shifted around a system. We shouldn’t fear this. Without complexity we become bored. Without complexity we wouldn’t have music and games. Therefore, seek simplicity but distrust it.

We were, of course, treated to an analysis of everyday things including light switches and, yes, doors. But the graphical user interface came in for the most critical insight. Norman believes that we are approaching a point at which the GUI is no longer scalable (consider trawling through icons of 15,000 photos on your hard drive). No doubt bringing a smile to Google’s face, Don believes search will become the dominant paradigm of the next age of UI.

Further thoughts

While the level was deliberately high to act as balance to the practical workshops that followed, I left with some conflicting thoughts. Monday’s talks were excellent, expansive, and expansionist. It’s important that we understand the context of design, but I firmly believe we must balance strategic interest with staying true to our own Buddha Nature: designing stuff. While there are occasions to broaden our scope, we should be mindful of diluting our message through landgrab. Our biggest mistake would be to believe our own hype too much; we are still seen as web designers, not saviours of the corporate world. We must prove our value if we are to be valued.

I also question our use of examples. As is typical of a UX conference, examples of what not to do abound. They’re a pure form of entertainment: funny and flattering to those in on the joke. However, there’s benefit in talking about good examples too – yet our portfolio is wearing sadly thin. Tivo (never popular in the UK), ClearRX and the ubiquitous iPod can only take us so far, and I hope we can soon talk about other successful examples of user experience design. If we can’t find any, perhaps we aren’t as effective as we hope?

However, these are all minor thoughts lingering after what I think was an excellent opening for our new conference. There are things we want to improve for next year (I’m particularly keen to involve a greater diversity of speakers), but we think the important stuff was more or less right. We hope others agree.

To close, an anecdote from Dan at White October. At the beginning of Leisa Reichelt‘s workshop, it appears she asked her audience to introduce and tag themselves, in the traditional BarCamp way. The most common tag? “Inspired”.

May links

In the absence of sufficient time to finish my drafts, some interesting reading

In the absence of sufficient time to finish my drafts, some interesting reading:

- The Dice-O-Matic — guy runs games server. Players complain of pseudo-random number generation. Guy builds gigantic dice rolling machine, capable of 1.3 million rolls a day.

- Burnout — new A List Apart article by Scott Boms. “Know thyself, but be gentle.”

- The Maturity Gap — thoughts on nurturing new UX talent.

- Please Say Something — wonderful animated short from the creator of Octocat.

- The ultimate ways to test your site — the official version of my previously-published article for .net. I didn’t choose the title.

- Caring For Your Introvert — a paean to the quiet underclass.

- Examining Game Pace: How Single-Player Levels Tick — fascinating analysis of pace and flow within game design.

I wouldn’t have got round to reading many of these if it weren’t for the marvellous Instapaper iPhone app, which I highly recommend. Having my to-read backlog to accompany my daily commute has been a godsend. More thoughts on the commute later.

Announcing UXCampLondon

Just a quick note for anyone who’s not heard: UXCampLondon will take place on Saturday 22 August at the Gumtree offices in London.

Just a quick note for anyone who’s not heard: UXCampLondon will take place on Saturday 22 August at the Gumtree offices in London.

For anyone unfamiliar with the BarCamp model, it’s a grass-roots ‘unconference’ born from the desire for people to share and learn in an open environment. All attendees give a talk, demo or some kind of session, and all are treated equally. No headliners, no product pitches, just a friendly (if intense) event focused on sharing and socialising as well as learning new stuff.

Although I’ll talk about it occasionally on this blog, most info will end up on the website (to be announced), the wiki page and on the UXCampLondon Twitter account. More info, including a website and ticket details, will be announced in the next few weeks.

Following up

I am not writing off the UK user experience scene. Far from it. I see UX as my calling, not just my career, and I’ll work as hard as I can to help it thrive here. And we are clearly on an exciting upward swing.

In a previous life I juggled a role that was equal parts information architecture and knowledge management. The fields are closer than you may think, both revolving around codifying, transferring and assimilating information.

Knowledge managers strive for the ‘watercooler moment’, where a colleague mentions in passing something that saves you weeks of work. There’s plenty of thought on how to engender this culture – even interior design has a role – but it can only ever come about by getting people talking. Sometimes, particularly in a fledgling community, this can be achieved via a social object.

My post last week (“Complex inferiority – user experience in the UK”) certainly generated the discussion I hoped for, with opinion split on whether I had a valid point and even whether my points were helpful or harmful. To that end it served its purpose, but I would like to clarify a couple of points.

I am not writing off the UK user experience scene. Far from it. I see UX as my calling, not just my career, and I’ll work as hard as I can to help it thrive here. And we are clearly on an exciting upward swing. However, I’m convinced that we need to be honest about where we must improve, and until we have (amongst other things) widespread mentoring, closer ties between academia and industry, more vocal discussion and a body of excellent work I will always see room for improvement.

Let me also be clear that I don’t advocate empty self-promotion. We don’t need rockstars. We need excellent people contributing to the community. My definition of a leader is someone who goes first, and encourages others to follow. Obviously I hope to contribute in whatever small way I can, but I urge anyone who cares about this scene to take the reins and try out new things to help our nascent community.

Complex inferiority: user experience in the UK

I think it’s time to examine why the UK hasn’t made its mark in user experience.

It’s a time of reflection in our field. However, as the drama unfolds on the mailing lists, I’ve been thinking closer to home.

Clearleft committed to UX London knowing that it would be the first major user experience conference on British soil. To an extent this made the decision easier, and gave us confidence that we’d meet our two main goals: first, to stimulate a buzz about user experience in the country and second, to create a profitable and worthwhile conference. That said, our predictions were conservative, particularly once the economy hit training budgets, and we expected steady sales right up until the event.

To sell out four months early was a wild surprise. The reason for this success (inasmuch as an event yet to take place can be called successful) is undoubtedly the calibre of speakers we’ve attracted. We targeted those acknowledged as pioneers of the field, through a simple selection process of debating, budgeting and arguing.

We soon realised that most speakers on our rapidly-expanding fantasy list were from the US. The chance to see luminaries from across the pond is a strong selling point for the conference, but I for one was disheartened that there weren’t stronger contenders based in the UK.

After all, Brits are major players in the web world. We’re the second most represented nation (10.8%) in the A List Apart survey, and in other areas of web design – particularly standards – we’ve built a strong community of practitioners and leaders, many of whom I’m lucky to know and work with.

I think it’s time to examine why the UK hasn’t made its mark in user experience.

Whither the rockstars?

Let me first explain that I hate the “rockstar” label. I use it only as an accepted term for someone widely admired who inspires others to success. Although the UK has some excellent practitioners, none has the profile or level of respect that, say, Messrs Norman, Merholz or Spool enjoy.

I recently posed a question on a couple of local forums: “Who is an inspiration in our field?”. It seemed innocuous enough and elicited interesting responses, but I must confess an ulterior motive. Totting up the nationalities of the names proposed quickly dispelled my concerns that I was merely projecting personal bias:

It seems safe to say that even we don’t see our community as a centre of user experience excellence.

It is hard to disagree. I consider the canon of UX literature and can barely think of a notable British author. Even online we’ve never produced an article with the impact of ia/recon, The Cognitive Style of Powerpoint or even The $300 Million Button.

Yet our practitioners are plentiful; just watch the steady stream of job ads and recruiter phonecalls. The London IA group has grown to nearly 500 members. Fifty people regularly dedicate their spare time to UX Book Club. Yet none of us has made a lasting mark on the field.

Perhaps it’s not rockstars we need. After all, it was only last month that JJG admonished the user experience field for celebrating those famous for talk, not action. So let’s look at that action. Can we find world class user experience work on these fair shores?

Our work

Happily, I think isolated pockets of excellent UX work exist: moo.com, the impressive new graze.com, and many national news organsations can all hold their heads high. However, if we examine some of Britain’s best-known dotcom successes – let’s say Lastminute, Betfair, last.fm, Gumtree, confused.com – none is by any means a paragon of user-centred design, although some are improving.

I am also struck by the level of our community discussion. We seem stuck in the domain of tactics: deliverables, Visio vs. Omnigraffle, “are there studies that prove x?” This is the bread and butter of UX, necessary but not sufficient, and I’m surprised at how few people are aiming higher. For all its infuriating problems, the IxDA list is full of discussion that truly stretches the limits of our environment: UX as design activity, getting a seat at the strategy table, the future of interaction. It seems these issues aren’t yet being taken seriously in Britain, which I believe greatly limits our scope to take user experience to the next level.

Education and mentoring

Although it’s a truism to say that education doesn’t meet the needs of the technology market, Britain has few post-graduate courses that adequately prepare students for a career in user experience.

Our best-known Masters courses include UCL’s HCI and Ergonomics, the RCA’s Design Interactions, and City University’s Human-Centred Systems. I’ve interviewed, spoken with and befriended many graduates from these programmes, and have even spoken a couple of times at UCL. My conclusion is that although these courses have some praiseworthy elements, British higher education seems stuck in the mindset of human-computer interaction. Think CHI papers, Jakob Nielsen, eyetracking; interesting stuff for sure, but of little relevance to practitioners. Only the RCA is perhaps an exception, although by some reports it too has fanciful flaws.

We need universities to offer practical design tutelage alongside the important theory. Ideally, education should be challenging industry at its own game and contributing directly to today’s practice. In the US, this is becoming a reality. CMU’s Interaction Design Masters is highly regarded, with alumni including Dan Saffer. New York’s School of Visual Arts has kicked off an MFA Interaction Design with a fantastic roster of industry talent.SCAD runs an Industrial Design Masters with a healthy Interaction Design component.

Although educational protocols are different in the US, it is nonetheless notable how so many American HE courses have such strong links with industry and leading-edge practice. We are far behind, and many British students are left struggling to catch up in their first role.

Our higher education needs to change its focus towards practical design, not Jakob andCHI papers. Responsibility for this lies not just with university staff. As practitioners, we need to take an interest in the activities of our educational system. It creates the future of our profession, and we cannot afford to abdicate our responsibility to help new entrants thrive.

We must also look at the needs of those who don’t or can’t take the formal route. Mentoring is an important way for our young field to grow, yet the IA Institute’s mentoring scheme lists just four mentors in the UK, compared to 49 in the US. It’s disappointing that there aren’t more people offering this kind of support, since many new UX designers need guidance and reassurance that in an emergent field like ours we are all to some extent learning it as we go.

Job market and culture

The vast majority of British user experience jobs are based in London, a notoriously fragmented city. There are few other British cities with the critical mass to sustain a community, so it’s essential that the capital has an active scene if the national community is to take off. Yet for years it lay dormant, with only the occasional UPA event to keep things ticking over. Fortunately this is changing, and I hope London can soon serve as a community example for other cities.

Britain also faces subtle issues around the culture of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial aspiration and startup rates are measurably lower than in the US. Although I have no data to confirm this, I suspect that user experience designers in Britain tend to work in larger companies where their influence may be limited. Certainly there have been few high-growth British startups with a strong UX focus, and despite the country’s strong design heritage, 43% of Britain’s businesses don’t invest in design at all.

Personality

Finally, I believe there’s a personal angle. The self-deprecating British nature and user experience designers’ tendencies toward thoughtful introversion means this is never going to be a group eager to shout from the rooftops. However, it is time for us to ignore the shackles of cultural norms and become more comfortable with minor self-aggrandisation. We won’t get far unless we share confidence in our work, our values and our worth to business, and to do this we need to become more vocal. No one will talk about our successes but us.

A silver lining

I’m sure there are causes beyond these infrastructural deficiencies. However, the combined effect has helped to create what until recently I described as an anaemic British user experience community.

Fortunately things are changing, and I’ve grown increasingly excited at the stirrings we’re showing. We’re starting to come together socially, and are organising new events to share what we’ve learned. The recent IA Mini conference and this summer’s UXCampLondon are important grass-roots continuations of this. UX London will hopefully cause some related get-togethers, and I’m also encouraged to hear that the UPA is looking to engage further with the community.

This activity is all to be welcomed, so long as we coordinate these efforts to avoid the harmful divisions currently seen in the US. It’s important to recognise those involved in setting up, attending and talking about these events, but we can’t leave it to a few. We need others to get involved and suggest new ways to foster our community.

The future of British UX

We’re finally showing some great momentum, and we desperately need to sustain it. To this end, we need community, and we need leaders. Not rockstars, but people who can help to spearhead the user experience movement in this country. In short, we need to get Britain talking about UX if we want the UX field to be talking about Britain.

We need to be visible and vocal. We need people to share their work and their thoughts. To debate, organise, write and present. We need more people to step forward both to organise events and act as mentors. We need to foster grass-roots activity and encourage cross-pollination. Designers across the country should mix, swap war stories and become friends. Practitioners and academia should be discussing how we can be more useful to each other.

After so long in the nest, it’s time our community took wings.

IA Summit 09 – days 2 and 3

The adversarial mood, no doubt exacerbated by economics, meant that the majority of off-stage discussion focused on the politics. However, it was mercifully balanced with a determination to unify and move on.

Maybe we’re finally getting back at all those cheerleaders.

The closing comments of Eric Reiss’s session A house divided summed up the IA Summit’s descent into angst, self-doubt and jealousy.

The tenth year of the Summit saw our field struggling with the onset of puberty. We’re stumbling towards an adult identity, while battling the conflicting voices amongst our ranks. It won’t be pretty but, like puberty, the necessary transformation will take us to new maturity.

But first, the content. Conference highlight Karl Fast used analogies from Tetris to describe usability testing. Studies show that skilled players over-rotate blocks to get a feel for how their shape will integrate with the current board. Yet classical usability theory would regard this as inefficient. How do we discriminate between errors and this epistemic action?

Fast also gave an overview of embodied cognition. In short, Descartes was wrong. Cognition is not just in the head; we also use our bodies to help shape our thoughts. This new theory of cognition presents problems. Our tactics, metaphors and patterns have been set up for a mind and body isolated. A finger here, an eyeball there. Mice, keyboards, touchscreens. None reflect the monism of embodied cognition.

Miles Rochford discussed the under-reported issues of IA for the rest of the world. It was a fascinating and sobering session that, like Fast’s, showed us how far we still have to go. Fred Beecher and Jared Spool also gave popular talks, but the Saturday focus was Eric’s. In this notorious session, he mixed mild personal censure with more welcome criticism of the IxDA’s divisive tribalism and the cult of ego over community. Applause and anger from the audience, which was probably the desired effect.

A similar sentiment was picked up by Jesse James Garrett in his closing plenary, in which he sounded the overdue death knell of division by job title. The information architect and the interaction designer are no more: we are all user experience designers, and we always have been. Amen.

JJG also called us out on our flimsy cult of celebrity. We have practitioners famous for what they say, rather than what they do. What great works of user experience have there been? Who made them? How have they made a difference? It’s a polemic that will surely go down as an important turning point for our profession. Every practising information architectuser experience designer should listen to it at the soonest opportunity.

The adversarial mood, no doubt exacerbated by economics, meant that the majority of off-stage discussion focused on the politics. However, it was mercifully balanced with a determination to unify and move on.

I’ve little interest in the petty politics of job titles, of IA Institute versus IxDA. However, I do care strongly about our combined future. It’s natural and healthy to air and resolve these conflicts rather than pretend there’s nothing wrong. Indeed, I see it as a mark of our growing maturity. But we must unify. In times of weakness, we need the strength of numbers, and this can only come from reversing the entropic breakdowns we’ve seen in recent years. Indeed, at the Sunday night meal there was a grass-roots movement to rename the conference (“The Memphis signatories”?) to simply The Summit, to reflect our new common agenda. Whether it works is to be seen, but I agree we need to change and broaden our focus if we are to find our true place in the world.

IA Summit 09 – day 1

It’s just one day, but it’s been fascinating and I’m sensing the stirrings of a breakthrough. Perhaps the pendulum of specialisation is swinging back, and the days of arguing over job titles and definitions can soon be dropped in favour of discussing what we have in common, and how we can all be better.

Seriously, 8.30am for a keynote? Not easy, particularly for those still getting used to Central Standard Time.

Michael Wesch‘s “Mediated Cultures” started laboriously, making points we’re all hopefully familiar with by now: changing media changes relationships, and so on. To quote the disillusioned Generation Y-er Wesch frequently referenced, “Whatever”. However, he soon livened up as we dived headlong into his preferred territory: internet counter-culture. Any keynote featuring 4chan’s Pedobear has to be deemed pretty interesting, and a welcome tone of openness and iconoclasm was set for all.

These themes have continued throughout the day. There does seem to be a genuine willingness here to tackle the issues and neuroses of the IA community, and perhaps even to overcome some of the divisons that we’ve so carefully constructed over the last few years. Whisper it quietly, but some even posited that, you know what, IA has been design all along. Eric Reiss’s session “RoI: Speaking the Language of Business” broke through some of the voodoo economics our forefathers* have been passing off for years, and implored us instead to sell the value of our services. The conclusion – focus on close, trusted relationships rather than mythical dollar values – seems dangerously close to that employed by design consultancies for generations. Similarly, Donna Spencer‘s Design Games session was pithy and direct, skillfully ignoring any nervous questions of process (“Why design games?” “What’s the deliverable?”).

Other sessions were patchy, as is to be expected of a blind review process, but the breaktime discussions as ever proved to be the really valuable moments. It’s been fantastic to connect with some very smart people, and I hope to continue in the same vein tonight and throughout the weekend.

It’s just one day, but it’s been fascinating and I’m sensing the stirrings of a breakthrough. Perhaps the pendulum of specialisation is swinging back, and the days of arguing over job titles and definitions can soon be dropped in favour of discussing what we have in common, and how we can all be better.

*Well, Jakob.

At the IA Summit

After six years, I’ve finally made it over to the Information Architecture Summit. This year it’s Memphis, and again it’s drawn an exciting group of people whose names (but not faces) are so familiar to me from all those articles, mailing lists and Twitter streams.

After six years, I’ve finally made it over to the Information Architecture Summit. This year it’s Memphis, and again it’s drawn an exciting group of people whose names (but not faces) are so familiar to me from all those articles, mailing lists and Twitter streams. Of course I’m here to learn from them, but I’m also here to network. As local UX types may know, I’m frustrated with the coy nature of the British scene and am hoping to pick up some tips on how we can raise our profile.

As the conference proper starts tomorrow, today was mostly set aside for settling in and meeting people. Inevitably, this included a group trip to Graceland, 8 miles down the road. Graceland is everything you’d expect: garish, crassly commercial, yet strangely intriguing. Part of the fun is analysing whether the lack of taste on display is representative of Elvis or merely the decade that dominates the property.

I’m hoping to give a daily wrap-up once we’re underway (liveblogging is too much like work, I’m afraid). If there’s sufficient demand, I might look into a quick “IA Summit recap” session back home for those unable to make it

Architecture of the stadium

This post is clearly an excuse for me to indulge a slight stadium fetish; however, I do think they provide great examples for how our identities, attitudes and actions can be shaped by the built environment. A branding exercise writ large in brick, if you will

People are often surprised to hear I’m a devoted football fan and Cardiff City supporter. Perhaps it doesn’t gel well with people’s perceptions of me (whatever those may be); however, I find football gives me an exciting break from daily concerns, and a chance to be part of the tribal culture inherent within us all. It’s a way to feel friendship with total strangers, an outlet for anger, joy and happiness, and an opportunity to mix with a wider cross-section of people than my limited horizons otherwise offer.

I also have a huge love for the stadiums and they remain one of the reasons I prefer to follow Cardiff at away games.

Stadium architecture has a clear effect on the physical presence of the club and atmosphere at games. The psychological effects on fans, referees and players are well-documented, but home advantage is also believed to give a genuine physical edge, hypothesised to be caused by testosterone increases in players. This effect is especially strong in defenders and goalkeepers, for whom the battle is particularly territorial.

Stadiums must also have logistics and facilities for up to 80,000 visitors (around the population of Shrewsbury), hundreds of police, stewards and officials, media and players. The range of requirements is pretty astonishing.

Clubs are known by the reputation of their grounds and the atmosphere they inspire. Some teams are known for poor support and quiet games (the “prawn sandwich“ brigade). Cardiff, on the other hand, have a reputation as a very intimidating club. There are many reasons for this: passionate fans, unfortunate hooliganism, and the constant battle to be noticed against Wales’ supposed national sport of rugby. However, the stadium plays a huge part too.

Ninian Park is a classic ‘old style’ stadium, well beyond its useful life yet still possessing the hallmarks of bygone eras: terracing, woeful facilities, and some intangible ‘character’. High among Cardiff fans’ many concerns for the future is the worry that atmosphere and indeed a piece of the club’s identity will be lost as we move into our new stadium (at top) in May.

On my travels with Cardiff I’ve been to some dismal grounds, and loved them all (a foggy January week night in Mansfield where you couldn’t even see the other end of the pitch comes to mind). Below, Watford’s stadium: ugly and an easy target for ridicule, but possessing far more character than many other grounds I’ve visited.

And then there’s always the rare occasion when your team performs and suddenly you find yourselves part of something huge:

This is my best shot from last year’s FA Cup Final, which Cardiff pretty much fluked our way into. Wembley is of course enormous, and again the atmosphere is shaped by the architecture. Expensive facilities and location make for expensive tickets. This (and the sponsorship derived from TV coverage) means money spare for banners, flags and other paraphenalia. Huge crowds make for huge expectations, high ceremony and lengthy big build-ups, but they also make co-ordinating singing impossible. Many Cardiff fans said they didn’t get the same sense of atmosphere as at a traditional away game, since the noisiest fans were spread across the ground rather than, as is common, concentrated in a group.

The nosebleed-inducing height also changes one’s experience of the match. From here you can see the sweep of the game, like a general, but not the blood and sweat of the touchline.

This post is clearly an excuse for me to indulge a slight stadium fetish; however, I do think they provide great examples for how our identities, attitudes and actions can be shaped by the built environment. A branding exercise writ large in brick, if you will.

Review: Sketching User Experiences

I found Sketching User Experiences to be an intelligent, far-reaching book that expanded my horizons but also left me somewhat frustrated.

As did many cities, London chose Bill Buxton’s Sketching User Experiences as the subject of the inaugural UX Book Club. I kicked off the discussion with my take on the book, and have hence decided to transform my notes into a written review for the benefit of anyone not present.

I found Sketching User Experiences to be an intelligent, far-reaching book that expanded my horizons but also left me somewhat frustrated. Buxton uses an inverted pyramid style, beginning broad and narrowing as he goes. This splits the book into what I felt were three sections (although Buxton himself declares only two parts: Design as Dreamcatcher andStories of Methods and Madness).

The first section, an analysis of the role of design, innovation and its business ecosystem, is to my mind the strongest. The ubiquitous iPod example surfaces early, but Buxton finds a way to inject this familiar narrative with fresh interest, by focusing on design strategy, acquisitions versus innovation, and the fundamental need for companies to create new stuff (faintly reminiscent of Marty Neumaier’s Zag). Buxton also elegantly dispels the myth that we cannot predict the future, demonstrating by historical example that supposedly new technologies typically have a minimum twenty year adoption curve.

The book then narrows to a discussion of process, asserting that “sketching is the one common action of designers”. I initially struggled with this definition, feeling it focused too much on visual output rather than our cognitive process. However, it soon becomes clear that Buxton isn’t interested so much in the sketch as artefact, but in sketching as an activity and a gerund. This culminates in his strongest chapter Clarity is not always the path to enlightenment which describes how sketching acts as a social object; the product of thought but also the catalyst for fresh ideas.

Sadly, from here, the book’s relevance declines. Examples and methods illustrated towards the end, while interesting, are clearly academic in their origin. As such, they may be fine for an M.A. project but, despite protestations of low overheads, they aren’t suitable for the fixed budgets and quick turnaround of agency user experience design. The latter sections are therefore at their best when they focus on simpler techniques. Chapters on tracing and photographs to as aids to sketching, and a convincing chapter on storytelling stand out.

I also remain unconvinced by the book’s overall stance. Buxton is a wonderfully knowledgeable author but his strong opinions often make Sketching User Experiences a paean to what I see as elitist practice. Big design up-front is regularly reinforced as the only worthwhile approach:

“Jumping in and immediately starting to build the product… is almost guaranteed to produce a mediocre product in which there is little innovation or market differentiation” (p141)

As a known Agile sympathiser, I have had Sketching User Experiences used as a weapon against me (“that’s not how Buxton says we do it”) and I found this narrow view hard to reconcile with my personal design ideology.

There are also small doses of intellectual arrogance that diminish the book’s impact. At the end of an unrealistic chapter on physical prototyping, Buxton asserts that any qualified interaction designer should be able to replicate this example in under thirty minutes. It’s a claim that begs the question of whether Buxton, or indeed anyone, has earned the right to impose their view of interaction design upon our community. The net result is that, although the book certainly helps designers, I’m not sure it helps the cause of design.

These ideological quibbles aside, I do recommend Sketching User Experiences. It was a strong choice for a book club and provided some good discussion points. It has also motivated me to draw more, to buy new Moleskines, improve the visibility of my sketching and sketches, focus on stories as important design tools, and to watch The Wizard Of Oz (you’ll see).

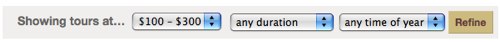

The making of Tourdust

A few weeks ago, a new travel startup called Tourdust quietly slipped into public release. It was my first major project for Clearleft, so I’d like to explain a little about the design process, challenges and decisions involved in its development.

A few weeks ago, a new travel startup called Tourdust quietly slipped into public release. It was my first major project for Clearleft, so I’d like to explain a little about the design process, challenges and decisions involved in its development.

Information architecture

The Tourdust proposition is a classic exploration of the long tail: linking offbeat, authentic tour experiences with travel geeks across the world. Think olive oil tours or bear watching, not package deals; a shared platform for small operations that may not even have websites of their own.

Since the site intends to house thousands of travel experiences, IA was a primary concern from the outset.Holidays involve a broad information space, with extensive metadata: duration, location, activity, organiser, price, availability, cost, and so on. Slicing through this data could be a daunting challenge for users, so an early task was to focus on how people understand and find travel experiences.

After design research, personas, scenarios and considerable thought, we concluded that the two critical factors in choosing an ‘active’ holiday (as opposed to a week sunbathing) werewhat the activity is and where it happens. It’s therefore no accident that these two variables are featured prominently on the site, as both navigation and headings. For a while, I even pressed (gently) for the site to be called everythingineverywhere.com.

Navigation

Since what and where operate independently of each other, they lend themselves well to faceted navigation. However, many faceted systems aren’t good at conveying their function, so we made the decision to split these two key variables off and turn them into primary navigation by means of dual nav bars, part breadcrumb and part hierarchical menu.

The other metadata is mostly taken care of by a “refine bar”. I believe it’s far better to show many results (particularly so in the early days when product numbers are low) and allow the user to trim the scope, than to create a bulky and elaborate “advanced search” feature that could confuse and easily return no results.

Unusual controls like these can be a risk; they’ll only be successful if users understand what they do, and how. The designer has to quickly suggest and demonstrate their operation through affordance and example. The affordance is largely visual: arrows, 3d overlap, and the behaviour of the menus as new options are selected. Demonstration by example occurs when a product is selected, possibly off the homepage. The dual nav is updated to show the intersection of activity and location (eg. “Cycling in Germany”), quickly establishing an understanding of how the controls work independently.

Of course, since these were uncommon controls, the proof was in the user testing. Paper prototypes were the order of the day here, mostly for budgetary reasons. Had more time been available we would have undoubtedly created HTML prototypes using Polypage to be watertight in our conclusions. However, they tested well for an unusual UI element and we felt confident this approach would allow for simple yet powerful navigation through this complex array of products.

Visual language

Another factor we agreed early on is that visual impact plays a huge role in the travel industry (not a massive leap of imagination, given the glossy large photographs seen in printed brochures). It was therefore very important for us to make the products as visually exciting as possible.

My early sketches involved very large, widescreen photos, and this detail was carried all the way into the final product. The widescreen format allows for some great detail of landscapes and panoramas, without the vertical overhead.

It also involves some tricky cropping mechanics. Most cameras take pictures with a 4×3 ratio (landscape) or 3×4 (portrait). The site halves the short side and instead uses an 8×3 ratio. Therefore, when a user—in this case, a tour operator—uploads an image, the system prompts them to crop the photo to show the top, middle or bottom half (the Maths is more complex for portrait shots). This cropping is initially done by clever CSS, repositioning the image vertically behind the 8×3 slot. Once a choice is made, the crop is made server-side for improved performance.

Process

We designed and built Tourdust as an Agile project, in collaboration with our Rails dev partners, New Bamboo. I’ve discussed the challenges of Agile design on A List Apart, but I believe that despite a few teething problems mid-project (mostly a cause of us not allowing enough lead time for design), the site is better than we could have created under waterfall methods.

In particular, since the clients were still exploring the business space whilst the site was being built, the business model changed halfway through development. With waterfall, this would have been beyond the point of no return, but with Agile’s flexibility we were able to accommodate the new requirements with only modest difficulty.

We also found ourselves fulfilling a strategic role as well as just designing the site experience. Frequently this involved reaching into the realms of service design, advising on features, functionality and proposition. One of the outcomes of this liaison was that great swathes of functionality were cut en route. “Worry about it when you need to worry about it” became a useful answer for many scalability questions. I think taking these bold decisions gives Tourdust more focus and a better user experience.

Endgame

Lest I paint too glowing a picture, the site isn’t perfect. Had we had more time, there are dozens of tweaks we’d have made. Imperfection is usually a tricky proposition for designers, particularly so at Clearleft: we do believe the devil is in the details, and our work is usually subjected to high scrutiny. Despite this, we’re proud of what was achieved on a modest budget, and hope we’ve given Anna and Ben the best platform to make Tourdust a success.

Of course, it’s a potentially difficult time to launch a startup. The recession is likely to dent the high-end, luxury travel market, meaning the site’s primary focus is currently on local, UK-based tours. But I do think, if the range is broad enough to gain traction, Tourdust can emerge on the other side in a strong position. I also couldn’t think of better people to take on this challenge than Anna and Ben. People who’ve put everything on the line to follow their dream are an inspiration, and it was a pleasure working with them. They’re true travel geeks and I think their confidence and love for the field will stand them in great stead.

Of course, it’s also down to the users, so I’d encourage you to have a play and I’d love to hear any comments you have about the site.

Why “best practice” must die

Anyone who’s worked in the web is aware of the “best practice” cult. To me, it’s a lazy creed that exhorts us to switch off and plunder others’ work, and the time has come to rebel.

Anyone who’s worked in the web is aware of the “best practice” cult. To me, it’s a lazy creed that exhorts us to switch off and plunder others’ work, and the time has come to rebel.

Firstly, there’s the pure language involved. “Best” implies something that cannot be improved upon. A world of best practice gives us creationism, chariots, and gramophones. It negates progress.

There’s also a more sinister side, which is when it’s wheeled out as an argument in design projects that are heading off the rails:

“Ah, but that’s not how eBay do it”.

The unspoken implication is that eBay know better than I, and therefore I should defer to their wisdom. It’s an argument that I find misguided more than insulting. “That’s not how eBay do it” is industrial, corporate thinking, entirely irrelevant to the 21st century. For the truth is that large companies often don’t have a clue about design. One’s skill and knowledge are entirely independent of the size of your employer: I’m confident I know as much about my profession as the employees at any large company.

The best practice trump card also fails because it doesn’t understand the nature of practical design. It’s not a transferable commodity: you can’t just screw a design solution into place. Good design must be appropriate and relevant to the particular problem. The factors involved—technological, strategic, sociological—are far too complex and variable for a plug and play approach. To say “Well, a dropdown worked here…” is to ignore factors that can actually work in your favour. A company that rejects the easy route and takes the time to understand technology, strategy and users can offer designs that makes it stand out from the rest.

I’m not advocating isolating oneself from the surrounding environment. For instance, at Clearleft, we regularly perform competitor analysis at the start of a project. It’s useful to see where others’ strengths and weaknesses lie, and helps us understand the landscape. However, not once has it given me the answer to a design problem. That always comes later, with thought, with detail, and after many failed attempts.

So let’s not allow the enforced limitation and unvoiced threats of “best practice” to pollute our thinking. It’s harder work, sure, but standing out and being better always is.

The h1 debate

Warning: There follows an arcane debate about HTML semantics, which will be extremely tedious to some.

Warning: There follows an arcane debate about HTML semantics, which will be extremely tedious to some.

Today has seen a minor revival of one the web’s perennial debates: whether the site header or page header is the most important. Its trivial intractability is perhaps only exceeded by the old UI chestnut of whether positive confirmation buttons should go on the left or right (think OK/Cancel versus Prev/Next). Frankly, it matters little, but I can’t sleep and I’m not one to miss out on a nuanced semantic debate.

Right now, you’re on my site Ineffable, reading a post The h1 debate. So which is the most important header on the page? Whichever is chosen should be marked up as <h1> (the HTML for the topmost header) for reasons of search engine optimisation, clean code, and so on.

The case for the site header

A purist might say that semantically and logically the site’s name is the primary tier. This would mean the hierarchy for this paragraph is: Ineffable > The h1 debate > The case for the site header.

While perhaps correct from an ontological perspective (a site has many articles, with many sub-sections), this has the drawback that the <h1> is the same for every page on the site. This is bad for search engines and may make orientation more different for those using screen readers. I also have a more fundamental concern, namely that this imposes a model that matches the designer’s understanding, but not the user’s.

The case for the page title

Pedantry is often important when it comes to good markup, but here I believe pragmatism must win out. This pragmatism arises when looking at the problem from the user’s perspective.

A user arriving at the site may indeed want to orientate themselves by seeing the name of the site, but their main goal is to find relevant information. This is particularly the case if they’ve come via a search engine, wherein they entered text of interest to them and leapt straight into the article itself.

The most important thing to a user is therefore what the page is about. This topic is far more likely to be represented by its title than the site name, and it’s logical that this title should be marked up as the <h1>.

My chosen hierarchy for this section is therefore The h1 debate > The case for the page title, with Ineffable possibly coming in as an <h3>. Note that, while an <h3> may be a subsection of <h2>, this isn’t demanded by the spec; and I think this is the right solution for this particular site.

This said, the answer may be that design classic “it depends” – with contributory factors including the size of the site, its purpose, and user behaviour. Particularly for small sites where users frequently navigate from the homepage down, I could see a site name <h1> being appropriate, while large sites with lots of ‘deep link’ traffic would be better suited by a page title <h1>.

Coping with a mainstream Twitter

The practical upshot is plenty of new users, including several of my real-life friends. While it’s great to have them on Twitter, I have my own selfish concern: will I be able to cope?

January was the month that Twitter lurched towards the British mainstream. Stats show an astronomical rise in site and search traffic, and the rich and famous are now falling over themselves to connect with their fawning public.

One may ask why this tipping point has happened first in the UK, rather than the States or elsewhere. One possible explanation is that a small number of influential celebrity types have hastened this outcome, and it’d be easy to fall into a daft sociocultural analysis of Britain the country and Britain the network. Stephen Fry as the powerful Gladwellian connector, uniting the geeks and the unwashed, previously so suspicious of each other!

My money’s on random chance. The initial conditions were set, after which chaos theory is the dominant force (yes, perhaps I have been listening to Jeremy too much).

The practical upshot is plenty of new users, including several of my real-life friends. They’re perhaps still on the early adopter side of mainstream but they’re not the type to, for instance, write blog posts about why people are joining Twitter. While it’s great to have them on Twitter, I have my own selfish concern: will I be able to cope?

I’ve previously mentioned that I have an approximate following threshold of 250. My workload and lifestyle enforce that personal limit, and I can’t realistically keep up to date with more people. So if my less geeky friends continue to join, whom do I drop? The model’s different from Facebook, where I can simply accumulate “friends” (a virtual notch on the bedpost) and then largely ignore them. So do I drop existing Twitterers, many whom I’ve never met but still give me a wealth of inspiration and knowledge, or friends whom I miss and am always eager to hear from? Ambient intimacy or friendship?

It’s a quandary. I’ve been trying to convince friends to join Twitter for a long time and it would be an irony if, once they join, I admit I don’t want to follow them. Yet I’m already operating a one-in-one-out policy, and something will have to give. My likely approach will be to take a much more relaxed and liberal approach to unfollowing people. Just as I’ll go and talk to various people at a party, so my attention will shift around a bit online. It’s either that or I face a cacophony in which I can hear no one.

However, I’m aware that people have very different attitudes to being unfollowed, so I’ll treat this post as a prophylactic excuse. Seriously, it’s not you, it’s me.

Can we avoid redesign backlash?

Your best strategy is to sweeten the deal with desirable functionality and an interface that matches users’ current mental models; if you don’t have those, batten down those hatches and prepare yourself for retaliation.

Users hate redesigns, or so we’re told. To be fair, the evidence does seem to support the argument: the last year or so has given us some clear examples of user backlash.

- Facebook: Right now, the largest anti-redesign group has 1,656,258 members. I’m with them in spirit: I think the Facebook redesign is weak, although it happens to suit my particular needs well (i.e. a lifestreaming service for non-geeks).

- last.fm: A site I dearly love, but whose redesign did little to address its IA problems, while introducing a gap-toothed NME-meets-Facebook visual direction that does it few favours. I wasn’t alone in my disappointment; there were quickly over 2,000 comments (warning: link may choke up your browser), often wildly negative.

- News sites: The Guardian, FT.com, and the BBC also transformed themselves within the last year, with ‘robust’ opinion voiced on each. News sites also have to handle the added complexity of politics: even if the Beeb were to find a cure for cancer, there would still be someone complaining it’s a waste of his licence fee.

All of these redesigns followed the familiar backlash pattern. To begin, post on your blog that you’re rolling out the redesign, and explain your rationale. Bonus points for words such as “widgets” and “personalised”. Having lit the touch paper, retire to a safe distance as the Kübler-Ross hatefest commences:

- Denial: “Why on earth did you change it?”, “The site was fine the way it was”

- Anger: “My twelve-year-old could have done better!”, “F—- you, I’ll never use this site again”

- Bargaining: “At least give us the option to use the old version…”

- Depression: “I used to love this site. Now I can’t bring myself to use it.”, “I miss [feature X] :(”

- Acceptance: “Actually, I’ve been using it for two weeks now and…”

The accepted wisdom on the cause of this backlash is that users learn how to navigate the site and achieve their goals, only for these strategies to prove useless in a redesign. Something akin to the way we learn the layout of a supermarket and optimise our routes accordingly.

I don’t buy this argument. Navigation may have a minor impact but users are notoriously good at satisficing—finding a good enough option—in unfamiliar waters. Instead, I think the reaction has a psychological basis. A favourite site has an emotional connection for us: we like it, it likes us, and we can depend each other. We fear the disruption of that equilibrium: a redesign raises the question of whether the site will grow in a direction we don’t want to follow. As Hugh MacLeod says in How To Be Creative:

Your friends may love you, but they don’t want you to change. If you change, then their dynamic with you also changes. They like things the way they are, that’s how they love you – the way you are, not the way you may become.Ergo, they have no incentive to see you change. And they will be resistant to anything that catalyzes it.

So, following from my earlier post, why has the New Xbox Experience (NXE) been so successful where other major redesigns have failed? Remember that this is Microsoft, a company not afforded the grace period that, say, Apple or Nintendo are.

My first thought is that the NXE is another good example of the MAYA principle in action. In particular, the quick interface, a cutdown version of the dashboard launched from within games, is structurally very similar to the old UI. I don’t know much about the NXE’s design process (although if anyone has any links I’d love to read them), but certainly it’s easy to imagine usability tests showing this was a welcomed feature.

The new UI also didn’t push boundaries particularly far, since in some areas it was simply catching up. The real value came not in the interface but in service innovation, incorporating new and desirable functionality (Netflix, HD installation) as a key part of the new design.

Compare this with Facebook’s lurch towards lifestreaming, which is at odds with the popular model of the site and therefore unlikely to appeal to many users. The public’s opinion seems to be that Facebook is a place to get in touch with people, rather than see what they’re up to. It could be argued that as friendship saturation reaches 100% (i.e. you have no friends left to add), lifestreaming becomes more useful. So perhaps Facebook are ahead of the anticipated user curve, but I doubt the 1,656,258 care.

We must also consider the fundamental question of whether a major redesign is wise idea in the first place. Jared Spool, for instance, argued long ago that big relaunches are dead. To a large extent I agree, and there are usually alternatives; for example, the classic eBay redesign story, which I assumed to be apocryphal but have been assured by insiders is true.

In a nutshell, a meaningless background was removed from a seller page. Pandemonium. After strong resistance the background was reinstated, to everyone’s satisfaction. In fact, the rebellious users were so placated that they failed to notice the designers slowly adjusting the background’s hex values over the next few months. The background got lighter and lighter until one day—pop!—it was gone.

To return to my initial question, I think it’s a brave and lucky company that can find a way to redesign without creating unrest amongst a large userbase. Your best strategy is to sweeten the deal with desirable functionality and an interface that matches users’ current mental models; if you don’t have those, batten down those hatches and prepare yourself for retaliation.