Technological trespassers

In 2018, philosopher Nathan Ballantyne coined the term epistemic trespassers to describe people who ‘have competence or expertise to make good judgments in one field, but move to another field where they lack competence—and pass judgment nevertheless.’

It’s a great label (for non-philosophy readers, epistemology is the study of knowledge), and an archetype we all recognise. Ballantyne calls out Richard Dawkins and Neil deGrasse Tyson, scientists who now proffer questionable opinions on theology and philosophy; recently we could point to discredited plagiarist Johann Hari’s writing on mental health, which has caused near-audible tooth-grinding from domain experts.

This is certainly a curse that afflicts the public intellectual. There are always new books to sell, and while the TV networks never linger on a single topic, they sure love a trusted talking head. Experts can grumble on the sidelines all they like; it’s audience that counts.

(As an aside, I also wonder about education’s role in this phenomenon. As a former bright kid who perhaps mildly underachieved since, I’ve been thinking about how certain education systems – particularly private schools – flatter intelligent, privileged children into believing they will naturally excel in whatever they do. Advice intended to boost self-assurance and ambition can easily instil arrogance instead, creating men – they’re almost always men, aren’t they? – who are, in Ballantyne’s words, ‘out of their league but highly confident nonetheless’. I can identify, shall we say.)

Within and without borders

Epistemic trespass is rampant in tech. The MBA-toting VC’s brainwormish threads on The Future of Art; the prominent Flash programmer who decides he’s a UX designer now. Social media has created thousands of niche tech microcelebrities, many of whom carry their audiences and clout to new topics without hesitation.

Within tech itself, this maybe isn’t a major crime. Dabbling got many of us here in the first place, and a field in flux will always invent new topics and trends that need diverse perspectives. But by definition, trespass happens on someone else’s property; it’s common to see a sideways disciplinary leap that puts a well-known figure ahead of existing practitioners in the attention queue.

This is certainly inefficient: rather than spending years figuring out the field, you could learn it in months by reading the right material or being mentored by an expert. But many techies have a weird conflicted dissonance of claiming to hate inefficiency while insisting on solving any interesting problem from first principles. I think it’s an ingrained habit now, but if it’s restricted to purely technical domains I’m not overly worried.

Once they leave the safe haven of the technical, though, technologists need to be far more cautious. As our industry finally wises up to its impacts, we now need to learn that many neighbouring fields – politics, sociology, ethics – are also minefields. Bad opinions here aren’t just wasteful, but harmful. An uninformed but widely shared reckon on NFTs is annoying; an uninformed, widely shared reckon on vaccines or electoral rights is outright dangerous.

Epistemic humility

Ballantyne offers the conscientious trespasser two pieces of advice: 1. dial down the confidence, 2. gain the new expertise you need. In short, practice epistemic humility.

There’s a trap in point 2. It’s easy to confuse knowledge and skills, or to assume one will naturally engender the other in time. Software engineers, for example, develop critical thinking skills which are certainly useful elsewhere, but simply applying critical thinking alone in new areas, without foundational domain knowledge, easily leads to flawed conclusions. ‘Fake it until you make it’ is almost always ethically suspect, but it’s doubly irresponsible outside your comfort zone and in dangerous lands.

No one wants gatekeeping, or to be pestered to stay in their lane, and there are always boundary questions that span multiple disciplines. But let’s approach these cases with humility, and stop seeing ourselves as the first brave explorers on any undiscovered shore.

We should recognise that while we may be able to offer something useful, we’re also flawed actors, hampered by our own lack of knowledge. Let’s build opinions like sandcastles, with curiosity but no great attachment, realising the central argument we missed may just act as the looming wave. This means putting the insight of others ahead of our own, and declining work – or better, referring it to others who can do it to a higher standard – while we seek out the partnerships or training we need to build our own knowledge and skills.

Scare-quote ethics

Forgive me, I need to sound off about “tech ethics”. Not the topic, though, but those fucking scare quotes: that ostentatious wink to the reader, made by someone who needs you to know they write the phrase with reluctance and heavy irony.

As you’ll see, this trend winds me up. I see it most often from a certain type of academic, particularly those with columns or some other visible presence/following. I love you folks, but can we cut this out? The insinuation – or sometimes the explicit argument – is “tech ethics” is meaningless; I have seen further and identified that the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house; these thinktanks are all funded by Facebook anyway; the issue is deeper and more structural.

As insights go, this is patently obvious. Of course the sorry state of modern tech has multi-layered causes, and of course our interventions need to address these various levels. Obviously there’s structural work to be done, not just tactical work.

But this is your classic ‘yes and’ situation, right? Pull every lever. Like, yes, I fully agree that the incentives of growth-era capitalism are the real problem. But we also need the tactical, immediate stuff that works within (while gently subverting?) existing limitations.

The problem with playing these outflanking cards, as we’ve seen from the web → UX → product → service → strategic design treadmill, is that as you demarcate wider and wider territory, your leverage ebbs away. You move from tangible change to trying to realign entire ecosystems. Genuinely, best of luck with it: it needs doing, but it takes decades, it takes power, and it takes politics. Most of those who try will fail.

I’m not equipped for that kind of work, so I do the work I am equipped for. Teaching engineers, students, and designers basic ethical techniques and thinking doesn’t solve the tech ecosystem’s problems. But I’ve seen it help in small, direct, meaningful ways. So I do it.

So please: spare us the scare quotes. Let’s recognise we’re on the same team, each doing the work we’re best positioned to do, intervening at the points in the system that we can actually affect, each doing what we can to help turn this ugly juggernaut around.

Expo 2020

Back from a let’s-say-unusual few weeks in Dubai. I was meant to give a big talk there – dignitaries/excellencies etc, etiquette-expanding stuff – but contracted this dread virus instead and for a while entertained visions of wheezing my intubated, asthmatic last many hours away from home. Happily the vaccines did their job and while isolation was grim, my symptoms were entirely weedy. Nonetheless, now I’m recovered, I elected to head home ASAP for hopefully understandable reasons, so had to withdraw from the event.

I was able to squeeze in a quick visit to Expo 2020, however. It deserves caveats. Yes, it’s teeming with cheesy robots and sweeping popsci generalisations about AI. Yes, its primary function is soft power and reputation laundering, although the queues outside the Belarus pavilion were noticeably short. But I still found it interesting, even touching. There’s something compelling and tbh just cool about bringing the world together to talk about futures – and also to do it in a creative, artistic, architectural, and cultural way that engages the public.

This is the kind of thing modern-era Britain finds deeply uncomfortable, I think. Excluding the flag-shagger fringe, national earnestness pokes uncomfortably against our forcefields, the barriers of cynicism we construct so we don’t have to look each other in the eye and confess our dreams. The only time fervent belonging ever really worked for us was 2012, and that was only thanks to home advantage.

But it has not escaped my attention that I’m an earnest dude and so, yeah: I enjoyed it. High-frequency grins behind the face mask, lots of mindless photos. Even the mediocre drone shows had some charm, although I drew the line at the ‘smart police station’.

It was also a fascinating toe-dip into other cultures. I’m not likely to see musical performance from subregions of Pakistan, nor a Saudi mass-unison song – swords aloft, dramatic lighting and everything – in my everyday life. I suppose new experience is the point of travel anyway.

Osaka 2025 is a long way off temporally and spatially but, you know, I’m tempted.

Poking at Web3

Like everyone, I’ve been trying to understand the ideas of Web3. Not the mechanics so much as the value proposition, I suppose. Enough people I respect see something worthwhile there to pique my curiosity, and the ‘lol right-click’ critique is tiresome. So I’m poking at the edges.

Honestly, it’s heavy going. The community’s energy is weird and cultish, and the ingroup syntax – both technical and social – is arcane to the point of impenetrability: whatever else Web3 needs, it’s crying out for competent designers and writers.

Most of the art is not to my taste, shall we say. Some of it’s outright dreadful. That’s forgivable. The bigger problem, though, is the centrality of the wallet, the token, and so on. I’m avowedly hostile to crypto’s ecological impact and its inegalitarian, ancappish positioning. Crypto folks have promised change is right around the corner for a long time now – call me when it finally happens.

So… grave reservations. But that aside, there is something conceptually appealing there, right? Mutual flourishing, squads, communities weaving support networks that heal system blindspots. I feel those urges too. Perhaps I’m just a dreamy leftist / ageing Millennial-X cusper, though, but my current solution to this is simple: give people cash. (More on that later, but as an aside, if you’re lucky enough to have money, consider throwing some at people who are trying to carve out fairer, less exploitative tech too. It’s not a lucrative corner of the industry.)

Anyway, I’m still a Web3 sceptic, but the intentions… yeah, they’re pretty cool. If the community can become more accessible and phase out the ugly stuff (most obviously proof-of-work blockchains, but also this notion that transactions are the true cornerstone of mutuality), I’ll be officially curious.

New role at the RCA

Starting as a (part-time) visiting lecturer at the Royal College of Art this week, teaching & mentoring MA Service Design students on ethical and responsible design. The next generation of designers have important work ahead, and I’m pleased to have the chance to influence them.

The law isn’t enough: we need ethics

When I talk about ethical technology, I hear a common objection: isn’t the law enough? Why do we need ethics?

It’s an appealing argument. After all, every country tries to base their laws on some notion of good and bad, and uses legality as a kind of moral baseline. While there are always slippery interpretations and degrees of severity, law tries to distinguish acceptable behaviour from behaviour that demands punishment. At some point we decide some acts are too harmful to allow, so we make them illegal and set appropriate punishments.

Law has another apparent advantage over ethics: it’s codified. Businesses in particular like the certainty of published definitions. The language may be arcane, but legal specialists can translate and advise what’s allowed and what isn’t. By comparison, ethics seems vague and subjective (it’s not, but that’s another article). Surely clear goalposts are better? If we just do what’s legal, doesn’t that make ethics irrelevant, an unnecessary complication?

It’s an appealing argument that doesn’t work out. The law isn’t a good enough moral baseline: we need ethics too.

Problem 1: Some legal acts are immoral

Liberal nations tread lightly on personal and interpersonal choices that have only minor impacts on wider society. Adultery is usually legal, as are offensive slurs, so long as they’re not directed at an individual or likely to cause wider harm. The right to protest is protected, even if you’re marching in support of awful, immoral causes. Some choices might lead to civil liabilities, but generally these aren’t criminal acts. Some nations are less forgiving, of course – we’ll discuss that in Problem 3.

Even serious moral wrongs can be legal. In 2015, pharma executive Martin Shkreli hiked the price of Daraprim, a drug used to treat HIV patients, from $13.50 to $750 a pill. A dreadful piece of price gouging, but legal; if we don’t like it, capitalism’s advice is to switch to an alternative provider. (Shkreli was later convicted of an unrelated crime.)

Or imagine you witness a young child drowning in a paddling pool. You could easily save her but you choose not to, idly watching as the child dies. This is morally repugnant behaviour, but in the UK, unless you have a duty of care – as the child’s parent, teacher, or minder, say – you’re not legally obligated to rescue the child.

Essentially, if we use the law as our moral baseline, we accept any behaviour except the criminal. It’s entirely possible to behave legally but still be cruel, unreliable, and unjust. This is a ghastly way to live, and we should resist it strongly; if everyone lived by this maxim alone, our society would be a far less trustworthy and more brutal place.

Fortunately, there are other incentives to go beyond the legal minimum. It’s no fun hanging out with someone who doesn’t get their round in, let alone someone who defrauds their employer. Unethical people and companies find themselves distrusted and even ostracised no matter whether their actions are legal or not: violate ethical expectations and you’ll still face consequences, even if you don’t end up in court.

Problem 2: Some moral acts are illegal

On the flip side, some behaviour is ethically justified even though it’s against the law.

When Extinction Rebellion protestors stood trial for vandalising Shell’s London headquarters, the judge told the jury that the law was unambiguous: they must convict the defendants of criminal damage. Nevertheless, the jurors chose to ignore the law and acquitted the protestors.

Disobeying unjust laws is a cornerstone of civil disobedience, helping to draw attention to injustice and pushing for legal and social reforms. In the UK, smoking marijuana is still illegal, despite clear evidence that it doesn’t cause significant social ills. Although I don’t enjoy it myself, I certainly can’t criticise a weed smoker on moral grounds, and the nation’s widespread disregard of this law makes future legalisation look likely.

There’s also a moral case for breaking some laws out of necessity. A man who steals bread to feed his starving family is a criminal, but we surely can’t condemn his actions. Hiding an innocent friend from your government’s secret police may be a moral good, but the illegality puts you at risk too: if you’re unlucky, you might find yourself strapped to the waterboard instead.

Problem 3: Laws change across times and cultures

The list of moral-but-illegal acts grows if we step back in time. Legality isn’t a fixed concern: not long ago, it was legal to own slaves, to deny women the vote, and to profit from child labour.

Martin Luther King Jr’s claim that ‘the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice’ gives us hope that we can right historical wrongs and craft laws that are closer to modern morality. But there are always setbacks. Look, for example, at central Europe today, where some right-wing populists are rolling back LGBTQ and abortion rights that most Western nations see as moral obligations.

If we equate the law and morality, aren’t we saying a change in the law must also represent a legitimate shift in moral attitudes? If a government reduces a speed limit, were we being immoral all those years we drove at 100kph rather than 80kph? Is chewing gum ethically wrong in Singapore but acceptable over the border in Malaysia? It can’t be right that a redrawing of legal boundaries is also a redrawing of ethical boundaries: there must be a distinction between the two.

There is, however, a trap here. Moral stances can vary across different times and cultures, but if we take that view to extremes, we succumb to moral relativism or subjectivism. These tell us that ethics is down to local or personal opinion, which leaves the conversation at a dead end. More on this in a future article, but for now I’ll point out that almost every culture agrees on certain rights and wrongs, and to make any progress we must accept some ethical stances are more compelling and defensible than others. Where moral attitudes vary, they still don’t move in lock-step with legal differences.

Problem 4: Invention outpaces the law

The final problem is particularly relevant for those of us who work in technology. Disruptive tech tends to emerge into a legal void. We can’t expect regulators to have anticipated every new innovation, each new device and use case, alongside all their unexpected social impacts. We can hope existing laws provide useful guidance anyway, but the tech sector is learning that new tech poses deep moral questions that simply aren’t covered by legal guidance. The advent of smart glasses alone will mean regulators will have to rethink plenty of privacy and IP law in the coming years.

We can and must push for better regulation of technology. That means helping lawmakers understand tech better, and bringing the public into the conversation too, so we’re not stuck in a technocratic vacuum. But that will take time, and can only ever reduce the legal ambiguity, not eliminate it. The gap between innovation and regulation is here to stay, meaning we’ll always need ethical stances of our own.

Double positive: thoughts on an overflow aesthetic

[Tenuous thoughts about the last two Low albums and (post)digital aesthetics…]

I think Low’s Double Negative (2018) is a legit masterpiece, a shocking right-angle for a band in their fourth active decade. Probably my favourite album of the century so far.

To describe the album’s sound, I’d have to reach for a word like ‘disintegration’. The songs are corroded, like they’re washed in acid, or a block of sandstone crumbling apart to reveal the form underneath. The obvious forefather is Basinski’s Disintegration Loops, which uses an analogue technology (tape and playhead) to create slow sonic degradation.

Double Negative’s vocals aren’t spared this erosion: they’re tarnished and warped to the point of frequent illegibility:

Reviewers pointed out Double Negative is the perfect sonic fit for its age. Organic, foreboding, polluted: as a metaphor for the dread and looming collapse we felt in the deepest Trump years, it’s on fucking point.

Hey What, released this month, is no masterpiece. But it’s still a great album, and like Double Negative I feel it’s also suited to its time. While the music is still heavily distorted, Hey What’s distortion is tellingly different. Rather than the sound being eroded, pushed below its original envelope, Hey What’s distortions come from excess, from overflow.

The idea of too much sound/too much information is how fuzz and overdrive pedals work, but this overflow is distinctly digital, not analogue. It’s not just amps turned up to 11 – it’s acute digital clipping, a virtual mixing desk studded with red warning lights, and millions of spare electrons sloshing around. More double positive than double negative. And unlike its predecessor, Hey What spares its vocals from this treatment, letting them soar as Low vocals historically do:

Brian Eno famously said ‘Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature.’ So yes, artists were always going to mess around with digital distortion and overflow once digital recording & DAWs became mainstream. I hear some of this experimentation in hyperpop, say, while autotune is arguably in the same conceptual ballpark. Although I’m no expert in contemporary visual culture, it seems clear to me the overflow vibe also crops up in digital art, supported by the NFT crowd in particular.

‘Something is happening here’ isn’t itself an exciting thesis, but I’ve found it interesting to poke at the connotations and associations of overflow. While Double Negative is all dread and collapse, Hey What is tonally bright. The world may not have changed all that much in three years, but the sound is nevertheless that of a band that’s come to terms with dread and chooses to meet it head-on: an equal and opposite reaction.

Hey What is still messy, challenging, and ambivalent, but to me, its overflow aesthetic evokes post-scarcity, a future of digitised abundance, in which every variation is algorithmically exploited, but with the human voice always audible above the grey goo. It suggests, dare I say, that we could live in (a bit of) hope.

So I guess I’m wondering… are Low solarpunk now?

Available for new projects

Wrapping up a major client, and a little time off, and at last have some capacity for future projects. Via Twitter thread, here’s a little reminder of what I do; please share with anyone who needs help making more responsible and ethical technology.

While I’m self-promoting, I’m told the World Usability Day (11 Nov) theme this year is trust, ethics, and integrity. I’m into that stuff. One advantage of the remote era is I can do multiple talks a day, so drop me a line if you need a keynote.

Oh, and I’m still interested in odd bit of of hands-on design, too. Turns out I’m still decent at it. Hit me up: cennydd@cennydd.com.

Book review: Design for Safety

Just sometimes, the responsible tech movement can be frustratingly myopic. Superintelligence and the addiction economy command the op-eds and documentaries while privacy and disinformation, important as they are, often seem captured by the field’s demagogic fringe. But there are other real and immediate threats we’ve overlooked. In Design for Safety, Eva PenzeyMoog pushes for user safety to be more prominent in the ethical tech conversation, pinpointing how technologies are exploited by abusers and how industry carelessness puts vulnerable users at risk.

The present tense is important here. The book’s sharpest observation, and the one that should sting readers the most, is that the damage is already happening. Anticipating potential harms is a large part of ethical tech practice: what could go wrong despite our best intentions? For PenzeyMoog, the issue isn’t conditional; she rightly points out abusers already track and harm victims using technology.

I’m very intentional about discussing that people will abuse our products rather than framing it in terms of what might happen. If abuse is possible, it’s only a matter of time until it happens. There is no might.

With each new technology, a new vector for domestic abuse and violence. We’re already familiar with the smart hauntings of IoT: abusers meddling with Nest thermostats or flicking on Hue lights, scaring and gaslighting victims. But the threat grows for newer forms of connected technology. Smart cars, cameras, and locks are doubly dangerous in the hands of abusers, who can infringe upon victims’ safety and privacy in their homes or even deny them a means to escape abuse.

While ethical tech books often lean closer to philosophy than practice, A Book Apart publishes works with a practical leaning. PenzeyMoog helpfully illustrates specific design tactics to reduce the risk of abuse, from increased friction for high-risk cases (an important tactic across much of responsible design), through offering proof of abuse through audit logging, to better protocols for joint account ownership: who gets custody of the algorithm after a separation?

Tactics like this need air cover. Given the industry’s blindspot for abuse, company leaders won’t sanction this extra work unless they understand its necessity. PenzeyMoog suggests public data is the most persuasive tool we have. It’s hard to argue against the alarming CDC stat that more than 1 in 3 women and more than 1 in 4 men in the US have experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner.

Central to PenzeyMoog’s process is an admission that empathy has limits. While we should certainly try to anticipate how our decisions may cause harm, our efforts will always be limited by our perspectives:

‘We can’t pretend that our empathy is as good as having lived those experiences ourselves. Empathy is not a stand-in for representation.’

The book therefore tackles this gap head-on, describing how to conduct primary research with both advocates and survivors, adding valuable advice on handling this task with sensitivity while managing your own emotional reaction to challenging testimony.

Tech writers and publishers often seem reluctant to call out bad practice in print, but Design for Safety is unafraid to talk about what really matters. One highlight is a heartening, entirely justified excoriation of Ring. Amazon’s smart doorbell is a dream for curtain-twitchers and authoritarians, eroding personal consent and private space. PenzeyMoog argues one of Ring’s biggest defects is that it pushes the legal and ethical burden onto individual users:

‘Most buyers will reasonably assume that if this product is on the market, using it as the advertising suggests is within their legal rights.’

That legal status is itself far from clear: twelve US states require that all parties in a conversation consent to audio recording. But the moral issue is more important. By claiming the law is a suitable moral baseline, Ring pulls a common sleight of hand, but for obvious reasons (countries and states have different laws; morality and law change with time; many unethical acts are legal) this is sheer sophistry. Ring has deep ethical deficiencies: we mustn’t allow this questionable appeal to legality deflect from the product’s issues.

Design for Safety also takes a welcome and brave stance on the conundrum of individual vs. systemic change. It’s popular today to wave away individual action, arguing it can’t make a dent in entrenched systems; climate campaigners are familiar with the whataboutery that decries energy giants while ignoring the consumer demand that precipitates these companies’ (admittedly awful) emissions. Design for Safety makes no such faulty dismissals. PenzeyMoog skilfully ‘yes and’s the argument, agreeing that attack on any one front will always be limited, but contending that we should push tactical product changes while also trying to influence internal and industry-level attitudes and incentives.

‘We don’t need to choose between individual-level and system-level changes; we can do both at once. In fact, we need to do both at once.’

This is precisely the passionate but clear-headed thinking we need from ethical technologists, and it makes Design for Safety an important addition to the responsible design canon. If I have a criticism, it’s the author’s decision to overlook harassment and abuse that originates in technology itself (particularly social media). Instead, PenzeyMoog focuses just on real-world abuse that’s amplified by technology. Having seen Twitter’s woeful inaction over Gamergate from the inside, I know that abuse that emanates from anonymous, hostile users of tech can also damage lives and leave disfiguring scars. The author points out other books on the topic exist – true, but few are written as well and as incisively as this.

Design for Safety is a convincing, actionable, and necessary book that should establish user safety as a frontier of modern design. Technologists are running out of excuses to ignore it.

Ethics statement: I purchased the book through my company NowNext, and received no payment or other incentive for the review. I was previously a paid columnist of A List Apart, the partner publisher of A Book Apart. There are no affiliate links on this post.

Basecamp and politics-free zones

Since social impact of tech is my bag, a few words on Basecamp’s recent statement. Most of the counters have already been made. Anyone who’s paid attention knows ‘apolitical’ is a delusional adjective: it means ‘aligned to the political status quo’. And of course there’s an embarrassing lack of privilege awareness in the statement/s. Opting out is a luxury many people don’t have.

However much they backtrack and narrow scope now, for me the message is clear: values-driven employees aren’t truly welcome at Basecamp. The leaders have that prerogative, sure, and their staff can decide whether that’s an environment they can flourish in.

I expect Basecamp will find this stance has a noticeable effect on future recruitment. The talent race is also an ethical race. But I also worry about the effect on product quality. If staff are scared to discuss ‘societal politics’ (what a tautology!), they’ll feel reticent to discuss the harms their work can do. And if you can’t discuss potential harms, you can’t mitigate them.

The talent race is also an ethical race

2020 was a bad year to be a worker. Laptops and cameras invaded our homes, whiteboard collaboration was replaced by Zoom glitches and Google Docs disarray, and any vestiges of work-life separation were blown away.

And that’s if you were one of the lucky ones. Millions were simply kicked out of jobs altogether, with Covid causing unprecedented drops in employment and hours worked. Further millions of essential workers had no choice but to continue working in unsafe environments. Thousands died.

After such a testing year, however, perhaps we’re turning a corner. The Economist, a newspaper hardly known for worker solidarity, predicts the arrival of a major power transfer. Through what I imagine are tightly clenched teeth, they describe an imminent swing, a ‘reversal of primacy of capital over labour’. If so, a golden age for workers beckons.

The theory goes that the post-Covid bounce will finally unleash employees’ pent-up frustrations. Eighteen months of working from the kitchen table has convinced many staff they’re done with meagre growth opportunities, stagnant pay, office politics, and – more than anything – the commute. Axios says 26% of employees plan to quit after Covid, while remote and hybrid work will untether the labour market from local employers, allowing people to reach for opportunities in other cities and countries. Talent flight may be a hallmark of the recovery as employees desert bad companies, and competition for top candidates becomes fiercer than ever.

For early signals of what happens when employees hold the cards, look at Big Tech. In-demand technologists are finally realising they hold enormous power. Their skills make them expensive and difficult to hire, and their mission-critical roles mean employees directly control a company’s output. Lift your hands off the keyboard and nothing gets built.

Tech workers are also starting to learn the trick to exploiting this power: collective action. An individual employee may be weak but, by banding together, employees can combine strengths while diluting risks.

This sort of mobilisation makes some executives nervous, in part because it looks like labour activism. Some worker-driven tech movements do focus on established labour issues like pay and conditions, and calls to unionise are gaining pace, thanks to the efforts of groups like the Tech Workers Coalition and industry leaders such as Ethan Marcotte.

But look closer at tech worker activism and you’ll see the primary focus is ethical. Google workers famously protested Project Maven – a Pentagon contract that could be used to aid drone strikes – on ethical grounds, expressing their displeasure through thousands of signatures on an an open letter and a handful of resignations. Shortly after Maven, the Google Walkout saw thousands of Googlers take part in brief wildcat strikes over allegations of sexual harassment at the company.

Other tech giants have since seen similar organisation. Amazon has faced internal employee rebellion over climate inaction and warehouse safety; Microsoft staff have come together to protest the company’s work with ICE.

So a swing toward worker power will also be an ethical transition. Salesforce found 79% of the US workforce would consider leaving an employer that demonstrates poor ethics, while 72% of staff want their companies to advocate for human rights. As opportunities start to open up for concerned workers, many will act on these beliefs and look for more moral employers.

Where Big Tech goes, the whole sector soon follows, and sure enough, ethical activism is a rising trend among tech workers worldwide. The #TechWontBuildIt movement typifies this emerging spirit of resistance, with thousands of technologists pledging to oppose and obstruct unethical projects.

This renewed ethical energy is here to stay and, with the eyes of regulators, press, and public alike now firmly on the tech sector, execs have to recognise the risks that await if they fumble the issue. Journalists have now realised compelling stories lurk inside the opaque tech giants and are eager for tales of dissent. Disharmony sells: if even pampered Silicon Valley types are unhappy, something is deeply amiss.

But the larger risk is around talent. Without outstanding and qualified employees you simply can’t compete – particularly in hot fields like data science and machine learning – but good candidates are increasingly dubious of Big Tech’s ethical credentials.

In firing AI ethicists Timnit Gebru and Meg Mitchell, Google leaders doubtless thought they’d found an opportunity to cut two demanding employees loose and proceed on mission. Instead, the company had blundered. The story made international headlines, and Google is now mired in allegations of retaliation. Gebru and Mitchell’s manager recently resigned amid the controversy, and Google’s reputation among data scientists and tech ethicists has been severely damaged. Canadian researcher Luke Stark turned down a $60,000 Google Research grant after the dismissals, and was only too happy to go on record to discuss his decision. Seems the ethics community’s solidarity is stronger than its ties to powerful employers and funders.

Facebook has also seen its candidate pool evaporating. Speaking to CNBC, several former Facebook recruiters reported the firm was struggling to close job offers. In 2016 around 90% of the offers Facebook to software engineering candidates made were accepted. By 2019, after Cambridge Analytica, allegations of cover-ups over electoral interference, and many other scandals, just 50% of the company’s offers were accepted.

Seeing their field as virtually a lifestyle, technologists know the industry intimately and recognize that toxic companies can blight a résumé. Many Uber employees who served during Travis Kalanick’s notorious reign found it difficult to land their next role; it seems hiring managers felt the company’s aggressive, regulation-dodging culture might undesirably infect their own teams.

So as companies stretch their limbs in preparation for the looming talent race, execs must remember this is also an ethical race. Tech workers are demanding that Silicon Valley look beyond disruption and hypergrowth and instead prioritise social impact, justice, and equity. As workers become more literate and confident in collective organising these calls will only get louder. Leaders may or may not agree with their employees’ demands, but the one thing they can’t do is ignore them. Money may still talk – but if the culture’s rotten, talent walks.

It’s fine to call it user testing

This linguistic canard does the rounds every few months, and UXers’ erroneous vehemence about it isn’t… healthy.

In the phrase ‘user testing’, the word user is a qualifying noun, also known as an attributive noun, or adjunct noun. As the name suggests, it modifies the second noun. (Here, testing is a gerund, a verb acting as a noun.) But that modification can have multiple meanings. Sometimes it implies of, but it can also imply, say, with, by, or for. Some languages add extra words for these distinctions; in English, we rely on the context to make it obvious.

‘Mobile design’ does not mean designing mobiles. It means designing for mobile.

‘Charcoal drawing’ does not mean drawing charcoal. It means drawing with charcoal.

‘Customer feedback’ is not feedback on customers. It means feedback from customers.

In 20 years, I’ve never met a client or colleague who thought ‘user testing’ meant actually testing users. Maybe you have. If so, my sympathies: your project likely faces problems more serious than this labelling issue.

There are a thousand more meaningful battles to pick, folks, and you might even be right about some of them. Let this one go.

All These Worlds Are Yours

Transcript of my keynote talk for Mind The Product, 19 Nov 2020. Rerecorded HD video above (37 minutes).

1 · utopian visions

If you’ll indulge me, I’d like to begin with some shameless nostalgia. Let’s step back a decade, to the heyday of techno-utopia.

Back in 2010, the mobile revolution had reached full pace. The whole world, and all its information, were just a tap away. Social media meant we could connect with people in ways we’d never dreamt of: whoever you were, you could find thousands of like-minded people across the globe, and they were all in your pocket every day. People flocked to Twitter, reconnected with old friends on Facebook. Analysts and tech prophets of the age wrote breathless thinkpieces about our decentralised, networked age, and promised that connected tech would transform the power dynamics of modern life; that obsolete hierarchies of society were being eroded as we spoke, and would collapse around us very soon.

And sure enough, the statues really did start to topple. The Arab Spring was hailed, at least in the West, as a triumph of the connected age: not only did smartphones help protesters to share information and mobilise quickly, but this happened in – let’s be honest – places the West has never considered technically advanced: Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, the Middle East… What a victory for progress, we thought. What a brave affirmation of liberal democracy, enabled and amplified by technology!

Still, there were a few dissenting voices, or at least a few that were heard. Evgeny Morozov criticised the tech industry’s solutionism – its habit of seeing tech as the answer to any possible problem. Nicholas Carr asked whether technology was affecting how we thought and remember. And growing numbers of users – mostly women or members of underrepresented minorities – complained they didn’t feel safe on these services we were otherwise so in love with.

But the industry wasn’t ready to listen. We were too enamoured by our successes and our maturing practices. Every recruiter asked candidates whether they wanted to change the world; every pitch deck talked about ‘democratising’ the technology of their choice.

We knew full well technology can have deep social impacts. We just assumed those impacts would always be positive.

Today, things look very different. The pace of innovation continues, but the utopian narrative is gone. You could argue the press has played a role in that; perhaps they saw an opportunity to land a few jabs at an industry that’s eroded a lot of their power. But mostly the tech industry only has itself to blame. We’ve shown ourselves to be largely undeserving of the power we hold and the trust we demand.

Over the last few years, we’ve served up repeated ethical missteps. Microsoft’s racist chatbot. Amazon’s surveillance doorbells that pipe data to local police forces. The semi-autonomous Uber that killed a pedestrian after classifying her as a bicycle. Twitter’s repeated failings on abuse that allowed the flourishing of Gamergate, a harassment campaign that wrote the playbook for the emerging alt-right. YouTube’s blind pursuit of engagement metrics that lead millions down a rabbit hole of radicalisation. Facebook’s emotional contagion study, in which they manipulated the emotional state of 689,000 users without consent.

The promises of decentralisation never came true either. The independent web is dead in the water: instead, a few major players have soaked up all the power, thanks to the dynamics of Metcalfe’s law and continued under-regulation. The first four public companies ever to reach a $1 trillion valuation were, in order, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Alphabet. Facebook’s getting close. Today, 8 of the 10 largest companies in the world by market cap are tech firms. In 2010, just 2 were.

It seems we’ve drifted some way from the promised course. Our technologies have had severe downsides as well as benefits; the decentralised dreams we were sold have somehow given way to centralised authority and power.

2 · slumping reputation

For some time, though, it wasn’t actually clear whether the public cared. Perhaps they were happy with dealing with a smaller number of players; perhaps they viewed these ethical scandals as irrelevant compared to the power and convenience they got from their devices?

Well, it’s no longer unclear.

Here’s some data from Pew Research on public attitudes toward the tech sector. It’s worth noting just how high the bar has been historically. The public has had very positive views of the industry for many years: there’s been a sort of halo effect surrounding the tech sector. But in the last few years there’s been a strong shift, a growing feeling that things are sliding downhill.

An interesting feature of this shift is that we see this sentiment across both political parties. We’ve heard a lot recently, particularly in the US, about how social media is allegedly biased against conservative viewpoints, or how YouTube’s algorithms are sympathetic to the far-right. But it seems hostility to the industry is now coming from both sides: perhaps this isn’t the partisan issue we’re told it is.

A common theme behind this trend is that people are mostly concerned about technology’s effects on the fabric of society, rather than on individuals.

This study from doteveryone captures the trend: the British public, in this case, feel the internet has been a good thing for them as individuals, but say the picture’s murkier when they’re asked about the impacts on collective wellbeing.

At the heart of this eroding confidence is an alarming lack of trust. In the same study, doteveryone found just 19% of the British public think tech companies design with their best interests in mind. Nineteen percent!

Frankly, this is an appalling finding, and one that should humble us all. But it also suggests a profound dissonance in how the public approaches technology. People are still buying technology, after all: the tech sector is doing well despite the Covid crash, and stocks are up significantly. The public clearly still finds technology useful and beneficial, but the data suggests people also feel disempowered, resigned to being exploited by their devices. It’s as if the general public loves technology despite our best efforts.

We’ve all witnessed this through the anecdotal distrust we see all around us. We all have a friend who’s convinced that Facebook is listening through their phone, that apps are tracking their every move. We all see this learned helplessness around us: there’s nothing I can do about it, so why fight it?

The other way this bubbles to the surface is through the dystopian media that’s sprung up around the topic. In particular, I’d point to two Netflix productions. Black Mirror is one, of course. It’s captured the public imagination through an almost universally grim depiction of technologised futures: as a collective work of dystopian design fiction it does its job admirably.

And then there’s The Social Dilemma, the recent documentary featuring Tristan Harris and other contrite Silicon Valley techies. It’s fair to say it’s not been well received in the tech ethics community: to be candid, the film’s guilty of the same manipulative hubris it accuses the industry of. But the fact a documentary like this got made – and has been widely quite successful – suggests the public’s starting to see technology as a threat, not just a saviour.

3 · dark futures

The risk is, of course, that things get even worse. The decade ahead of us could well unleash deeper technological dangers. Certainly we’ll see disinformation and conspiracy playing a deeper role in social media, particularly with the advent of synthetic media – deepfake computer-generated audio and video, in other words – that blur the line even more between what seems real and what is real.

Right now we think of facial recognition mostly as a tool for personal identification – unlocking our phones, focusing cameras, tagging friends on nights out. But facial recognition is already wriggling beyond this personal locus of control. It’s going to colonise whole cities, and in turn pose quite serious threats to human rights.

Once you can identify people at distance and without consent, you can also map out their friendships, and assemble a ‘hypermap’ of not just their present movements, but also their past actions, from video footage recorded maybe years ago. It’s a short enough step from there to an automated law enforcement dragnet: a list of anyone who fits a certain description in a certain time and place, issued to anyone with a badge and an algorithm.

There are already movements underway to ban police and governments from using facial recognition on the general public: these might be successful in some cities or countries, but that battle will have to be won over and over again with each new terrorist attack. And authoritarian regimes won’t show the same sort of restraint that liberal states might.

As more companies and states put faith in artificial intelligence, we’ll also see more algorithmic decisions. Although as a community we’re starting to wise up to the dangers of algorithmic bias, it’s still likely that the people commissioning these systems will see them as objective, neutral, infallible tellers of truth. Even if that were true – which, of course, it’s not – citizens will rightly start to demand that these systems should explain the decisions they take. That’s tough luck for anyone relying on a deep learning system, which is computationally and mathematically opaque thanks to its design. I’m not sure we’ll be happy to sacrifice that power to satisfy what might seem like a pedantic request. But I’d argue perhaps we should: surely an important right within a democracy is to know why decisions are taken about you?

My biggest worry is when algorithmic decisions creep into military scenarios. Autonomous weapons systems are enormously appealing in theory: untiring, replaceable, scalable at low marginal cost. They could also cause carnage in ways obvious to anyone who’s watched a science fiction film since, what… 1968? There are some attempts to ban autonomous weapons too; the countries dragging their heels are pretty much the countries you’d expect.

2020 was, at last, the year the 21st century lived up to its threats. It was the first year that didn’t feel like an afterbirth of the 19-somethings; a year in which historic fires burned, racial tensions ignited, and an all-too-predictable and -predicted pandemic exposed just how ready some governments are to sacrifice their citizens for the good of the markets.

The coming decade might be worse still. I appreciate we’re all feeling temporarily buoyed by welcome uplifts at the tail-end of a dreadful year – vaccines around the corner, a disastrous head of state facing imminent removal – but the fundamental rot hasn’t been addressed. Deep inequality is still with us; automation still threatens to uproot our economies and livelihoods; vast climate disruption is now guaranteed: the only unknown is how severe that disruption will be.

But let’s take a breather: I don’t want to collapse into dismay. Let’s come back to the issues we control: the fate of the technology industry. How did we get here? What went wrong?

4 · responsibility as blame

I’ve been in the field of ethical and responsible technology for maybe four or five years now, after fifteen as a working designer in Silicon Valley and UK tech firms. If I may, I’d like to share one of the patterns I’m most confident about, having seen it repeatedly during that time.

Product managers are the primary cause of ethical harm in the tech industry.

It’s a blunt claim, and perhaps not a popular claim to make at a huge product conference. I feel I need to offer some caveats, or partial excuses. Maybe that old classic – some of my best friends are product managers. I’m even married to one. But there’s a more important point: this pattern is not intentional.

I’d be lying if I said I’ve never met a PM who relishes acting unethically: sadly, I have met one or two. But the vast majority of PMs – the ones who don’t demonstrate borderline sociopathy – mean well, and want to do well. Many of them have been reliable, valuable partners of mine in flourishing teams. Many of them care deeply about ethics and responsibility and want to take these issues seriously.

But I still see teams taking irresponsible decisions with damaging consequences. I think it happens because these consequences are unfortunate by-products of the things the product community values, the way PMs take decisions, and the skewed loyalties I think this field has adopted.

5 · empirical ideologies

Let’s talk first about Lean. I remember shortly after Eric Ries’s book, The Lean Startup, came out: every company I spoke with thought they were unique in adopting Lean methods. Now everyone does. Lean isn’t just a set of methods any more: it’s become an ideology. And the problem with ideologies is they’re pretty hard to shift.

One of the central precepts behind Lean Startup is that we now live in a state of such constant flux and extreme uncertainty that prediction is an unreliable guide.

‘As the world becomes more uncertain, it gets harder and harder to predict the future. The old management methods are not up to the task.’ —Eric Ries.

Instead, we should put our faith in empirical methods: create a hypothesis, then build, measure, learn, build, measure, learn. It’s all about validating your assumptions through a tight, accelerated feedback loop.

Makes sense. As a way to reduce internal waste and to stagger your way to product-market fit, I can see the appeal. But I also think there’s a major flaw in this way of thinking: it leaves no space, no opportunity to anticipate the damage our decisions might cause. It abandons the idea of considering the potential unintended consequences of our work and mitigating any harms.

It brings to mind that phrase that’s come to haunt our industry: move fast and break things. Breaking things is fine if you’re only breaking a filter UI. It’s not fine if you’re breaking relationships, communities, democracy. These pieces do not fit back together again in the point release. This idea of validated learning and incremental shipping has caused teams to casually pump ethical harm in the world, to only care about wider social impacts when they have a post-launch effect on metrics.

6 · overquantification

Believers in Lean ideologies also tend to have a strong bias toward metrics. and the belief that the only things that matter are things that can be measured. Numbers are valuable advisers but tyrannical masters. This leads to a common PM illness of overquantification, a disease that’s particularly infectious in data-driven companies.

Overquantification is a narrow, blinkered view of the world, and again one that makes ethical mistakes more likely. Ethical impacts are hard to measure: they’re all about very human and social qualities like fairness, justice, or happiness. These things don’t yield easily to numerical analysis. That means they tend to fall outside the interests of overquantified, data-driven companies.

I think a lot of people think Lean offers us a robust scientific method for finding product-market fit. I’d say it’s more a pseudoscience, but ok. It makes sense, then, that this idea of validated learning lends itself very well to experimentation: in fact, Lean Startup says that all products are themselves experiments. So a lot of Lean adherents rely heavily on A/B and multivariate testing as a way to tighten that feedback loop.

Product experiments can be a useful input to the design process; they can help you learn more about which approaches are successful, they can help you optimise conversion rates, and all that. But I’ve also witnessed companies where the framing of experimentation shifts. Instead of A/B and multivariate tests providing data points for validated learning, they start to become tools of behaviour manipulation. Without realising it, teams start talking about users as experimental subjects; and experiments become about find the best way to nudge or cajole users to behave in ways that make more money.

If you’re in this state – when you start thinking of users as masses, as aggregate red lines creeping up Tableau dashboards – you’re already beyond the ethical line. When you start thinking of people as not ends in their own right, but as means for you to achieve your own goals, you’re already in the jaws of unethical practice.

7 · business drift

I think we can trace the root of this tendency to a shift in the priorities of Product teams.

I’m sure most of us are familiar with this Venn diagram: I knew of it long ago; it was only very recently I found out it was created by Martin Eriksson himself.

This diagram shows Product managers sitting at the intersection of UX, tech, and business. I like it as a framing. It’s a hell of a lot better, for example, than that arrogant trope about PMs being the CEO of a product. But what I’ve observed, though, is this isn’t really what happens. Or perhaps it once used to, but there’s been a drift.

Far too many product managers have drifted into the lower circle. They’ve become metrics-chasers, business-optimisers, wringing every last drop of value out of customers and losing sight of this more balanced worldview.

I can understand this drift. Being on the business’s side is a comfortable place to be. You’ll always feel you have air cover, always feel supported by the higher-ups, always feel safe in your role. And you’ll also be biasing your team to cut ethical corners to hit their OKRs.

8 · user-centricity causes externalities

One more root cause to mention, and this one isn’t just about product managers, but designers too. To realise lasting business value, we’re taught we have to focus with laser precision on the needs of users.

This, too, has to change. We’re starting to learn, later than we should have, that user-centred design doesn’t really work in the twenty-first century. Or at least, it has significant blindspots.

The problem with focusing on users is our work doesn’t just affect users. The biggest advantage digital businesses have is scale: they can grow to serve huge numbers of customers at very low marginal cost. It’s not that much more expensive to run a search engine with 1 billion users than 1 million users. Create a social platform that catches fire and you might find yourself with 100 million users in a matter of a few months.

We’re now talking about global-scale, human-scale impact. Technologies of this scale don’t just affect users; they also affect non-users, groups, and communities. If you live next door to an Airbnb, your life changes, likely for the worse. Your new neighbours won’t care so much about the wellbeing of your community; they’ll be more likely to spend their money in the tourist traps than in the local small businesses; and, of course, their presence pushes up rents throughout the neighbourhood.

From a UX and product point of view, Airbnb is a fantastic service. It’s a classic two-sided platform that connects user groups for mutual gain. But all the costs, the harms, the externalities fall on people who haven’t used Airbnb at all: neighbours, local businesses, taxpayers… User-centricity has failed these people. Product-market fit has caused them harm.

Large-scale technologies don’t just affect groups of people. They also affect social goods: in other words, concepts we think are valuable in society. There’s been a lot of talk about how Facebook, for example, has torn the fabric of democracy. Some sociologists and psychologists say Instagram filters could damage young people’s self-image. These values simply aren’t accounted for in user-centred thinking: we see them as abstract concepts, unquantifiable, out of scope for tangible product work.

And then there’s non-human life, which our current economic models see just as a resource awaiting exploitation, as latent value ready for harvest. Humans have routinely exploited animals in the name of progress. Think of poor Laika, sent to die in orbit, or the stray animals Thomas Edison electrocuted to discredit his rivals’s alternating current.

Alongside this, there’s the very health of the planet. The news on climate crisis is so terrifyingly bad, so abject, that it’s immoral to continue to build businesses and to design services that overlook the importance of our shared commons. Climate is the moral issue of our century: there’s no such thing as minimum viable icecaps.

So even if product managers position themselves at the heart of UX, tech, and business, they may well be missing their moral duties to this broader set of stakeholders, to non-users, to groups and communities, to social structures, nonhuman life, and our planet itself.

9 · it doesn’t have to be this way

I’ve been talking about some dark futures for technology and for our world. The good news is that it doesn’t have to be this way. One of the things any good futurist will tell you is that the future is plural. It’s not a single road ahead: it’s a network of potential paths. Some are paved, some muddy; some are steep, some are downhill. But we get to choose which route we take.

Sometimes I’m sharply critical of our industry, but please don’t misunderstand me. I truly believe technology can improve our world, can improve the lot of our species. Technology can help bring about better worlds to come. If I didn’t believe that, I wouldn’t still be doing this work.

What it will take, however, is for us to reevaluate our impacts along new axes: to actively seek out a more ethical, more responsible course.

In retrospect, we’ll look back on 2020 as a pivotal year. I’m sceptical of some of the grand narratives people offer about the post-Covid world, but I do think it’s true that the deck of possible futures has been thoroughly shuffled this year. We now have the opportunity to choose new directions. We might not get a reset of this magnitude again.

And I want you – the product community – to lead this charge. I expect it’s hard to appreciate this from the inside, but you all hold an immense amount of power within technology companies, and within the world. You are the professionals whose decisions will shape our companies and products; your decisions will change how billions of future users interact with technologies and, by extension, with each other. I want you to exercise that power with thought and compassion.

If this is going to happen, you need to rethink what you value; what drives your processes and decisions. That’s, by necessity, a long journey. It’ll involve lots of learning, plenty of failure. For the rest of my time here, I’d like to suggest some first steps.

Here’s my fairly crude attempt to illustrate a responsible innovation process; let’s step through what it might mean for you.

10 · carving out space for ethical discussion

Perhaps most importantly, teams need to make space in their processes for ethical deliberations, to examine potential negative impacts, and look for ways to fix them before they happen. It doesn’t really matter when this takes place. You could adapt an existing ritual: a design critique, a sprint demo, a retro, a project pitch. Or maybe you ring-fence time some other way. But you must try.

When you do this, be prepared: someone will tell you it’s a waste of time. People use technologies in unpredictable ways, they’ll say: we can’t possibly foresee all of those. They might even quote the ‘law of unintended consequences’ at you, which says pretty much the same thing: you’ll always miss something.

Don’t listen. It is true that you’ll never foresee all the consequences of your decisions. But anticipating and mitigating even a few of those impacts is far better than doing nothing. And moral imagination, as we’d call it, isn’t a gift that only a few lucky souls have: it’s more like a muscle. It gets stronger with exercise. Maybe you only anticipate 30% of the potential harms this time around. Next time it might be 40%. 50%.

The easiest way to get started on this is a simple risk-mapping exercise: a set of prompt categories and questions you can run through to identify potential trouble spots. I recommend using the Ethical Explorer toolkit as a starting point; it’s been made by Omidyar Network for exactly this use case. It’s free and doesn’t need any special training to use.

11 · getting out of the building

Eventually you’ll realise this isn’t enough of course. Trying to conjure up potential unintended impacts from inside a meeting room or a Zoom call is worth doing, but is always going to be limited. Soon enough you’ll want to get out of the building.

You know this idea from customer development, of course. You know that talking with real people opens your eyes to new perspectives like nothing else can – that it helps you move from empathy to insight. So talk to your researchers about ways to better understand ethical impacts. I promise they’ll be delighted to help you: anything that’s not another usability test will make their eyes light up.

But remember here, it’s not just about individual users: it’s worth broadening your research to hear from other stakeholders. So look for ways to give voice to members of communities and groups, particularly if they’re usually underheard in this space. Reach out to activists and advocates. Listen to their experiences, understand their fears; work with them to prototype new approaches that reduce the risks they foresee.

12 · learning about ethics

Spotting potential harms in advance is a great start, but you then need to assess and evaluate them. Which are the problems that really matter? What do we consider in scope, and what’s outside our control? How do we weigh up competing benefits and harms?

There’s plenty of existing work to help us answer these questions. Plenty of people in the tech industry share an infuriating habit: they believe they’re the first brave explorers on any new shore. But this isn’t a topic to invent from scratch. There’s so much we can, and should, learn from the people already in this space.

When I moved into the field of ethical tech, around five years ago, I was stunned by the depth and quality of work that was already going on behind the industry’s back. Ethics isn’t about dusty tomes and dead Greeks! It’s a vital, living topic, full of artists, writers, philosophers, and critics, all exploring the most important questions facing us today: How should we live? What is the right way to act?

There’s a happening in this movement, and a lot to learn. Some people think ethics is fuzzy, subjective, difficult. If you take the time to deepen your knowledge, you’ll realise this isn’t really true. There’s strong groundwork that’s already been laid: there are robust ways to work through ethical problems. You can use these to take defensible decisions that make your team proud.

13 · committing to action

You then have to commit to action. There’s a sadly common trend these days of ethics-washing – companies going through performative public steps to present a responsible image but unwilling to make the changes that really matter. An ethical company has to be willing to take decisions in new ways, to act according to different priorities, if you’re going to live up to these promises.

Maybe it’s something simple, like committing as a team to never ship another dark pattern. Maybe it’s ensuring your MVP includes basic user safety features, so you reduce the risk that vulnerable people are harassed or attacked.

I particularly want to mention product experimentation here. It astounds me how ethically lax our industry is when it comes to experimentation. Experimentation and A/B testing is participant research! In my view, this means you have a moral obligation to get informed consent for it. So tell customers that A/B tests are going on. Let people find out which buckets they’re in and, crucially, offer them a chance to opt out. Be sure that you remove children from experimental buckets.

14 · positive opportunities

But this step isn’t just about mitigating harms. One welcome trend I’ve seen is that the conversation about ethics is moving beyond risk. Companies are starting to realise that responsible practices are also a commercial advantage.

Jonathan Haidt, who’s a professor of business ethics at NYU, has found that companies with a positive ethical reputation can command higher prices, pay less for capital, and land better talent.

There’s plenty of evidence that customers want companies to show strong values. Salesforce Research found 86% of US consumers are more loyal to companies that demonstrate good ethics. 75% would consider not doing business with companies that don’t.

So this stage also means capitalising on opportunities you spot in your anticipation work. This means thinking differently about ethics.

I think too many people see ethics as a negative force: obstructive, abstract, something that be a drag on innovation. I see it differently. Yes, ethical investment will help you avoid painful mistakes and dodge some risks. But ethics can be a seed of innovation, not just a constraint.

The analogy I keep returning to is a trellis. Your commitment to ethics builds a frame around which your products can grow. They’ll take on the shape of your values. Your thoughtfulness, your compassion, and your honesty will reveal themselves through the details of your products.

And that’s a powerful advantage. It’ll help you stand out in wildly crowded marketplace. It can help you make better decisions, and build trust that keeps customers loyal for life.

As this way of thinking become more of a habit, you need to support its development. A one-off process isn’t much good to anyone: you need to build your team’s capacity, processes, and skills, so responsible innovation becomes an ethos, not just a checklist.

So you need to spend some time creating what I call ethical infrastructure. This might include publishing a set of responsible guidelines for your team or your company. Maybe it’s including ethical behaviours in career ladders. Perhaps in some cases you’ll want to create some ethical oversight – a committee, a team, or at least a documented process for working through tough ethical calls.

It’s easy to go too quickly with this stuff, and build infrastructure you don’t yet need. Keep it light. Match the infrastructure to your need, to your team’s maturity with these issues. If you keep your eyes open, it’ll soon become clear what support you need.

15 · close

These are still pretty early days for the responsible tech movement. We may be stumbling around in the gloom, but we’re starting to find our way around. Personally, I find it thrilling – and challenging – to be in this nascent space. Something exciting is building: maybe there’s hope for an era of responsible innovation to come.

Because we’re starting to realise we won’t survive the 21st century with the methods of the 20th. We’re beginning to understand how user-centricity has blinded us to our wider responsibilities; that the externalities of our work are actually liabilities. Business are learning they have to move past narrow profit-centred definitions of success, and actively embrace their broader social roles.

After all, we’re human beings, not just employees or directors. Our loyalties must be to the world, not just our OKRs.

Wherever it is we’re headed, we’ll need support, courage, and responsibility. My product friends, you have a power to influence our futures that very few other professions have. All these worlds are yours: you just have to choose which worlds you want.

Norman on ‘To Create a Better Society’

Don Norman’s latest piece ‘To Create a Better Society’ has me rather torn.

First, I worry about the view that designers should be the leaders on social problems. We can/should engage with these issues, but respectfully and collaboratively. We don’t need Republic-esque designer-philosopher-kings. Facilitation yes, domination no. I’m sure this is not Norman’s intent, but some of the language is IMO too strong.

Second, and more seriously, Norman has been hostile to people pushing some of these very ideas in recent years. They deserve credit for handling his attacks with dignity and (whether he appreciates it or not) ultimately shifting his perspectives.

That aside, a design luminary arguing that commercial priorities have pushed aside the topics of power, ethics, and ecology in design, and that design should become less Western-centric & colonial… well, we need more of that kind of talk.

Tips for remote workshops

Some lessons I learned from running five days of remote workshops.

Even more breaks than you think you need. Ten minutes every hour. Gaps between days, too. I couldn’t stomach the grisly prospect of Mon–Fri solid, so we ran Tue/Wed → Fri → Mon/Tue. Life-saving.

Use a proper microphone. My voice nearly gave out on day 1 because I hadn’t plugged in, and ended up resorting to my videocall voice. Wasn’t a problem once I dug the Røde out.

Use the clock for prompt time-keeping – ‘see you all at 11:05’ – and restart on the dot, so attendees know you mean it.

Be alert to, and accommodate, chat: my group fell into a great pattern of using it for non-interrupting questions.

Childlock everything in Miro. Lock and hide boards, pre-drag stickies. That thing’s only usable if you sharply reduce degrees of available freedom.

Set and enforce a ground-rule that any camera-visible cats must be introduced to the group. We stopped three times; one of the best decisions I made.

Anyway, it reminded me of Twitch streaming, except you can see the audience, and it’s less fun but far better paid. In all, I think our sessions went damn well. Would still far rather have done them in person, but we overcame some of my scepticism. A good group goes a long way.

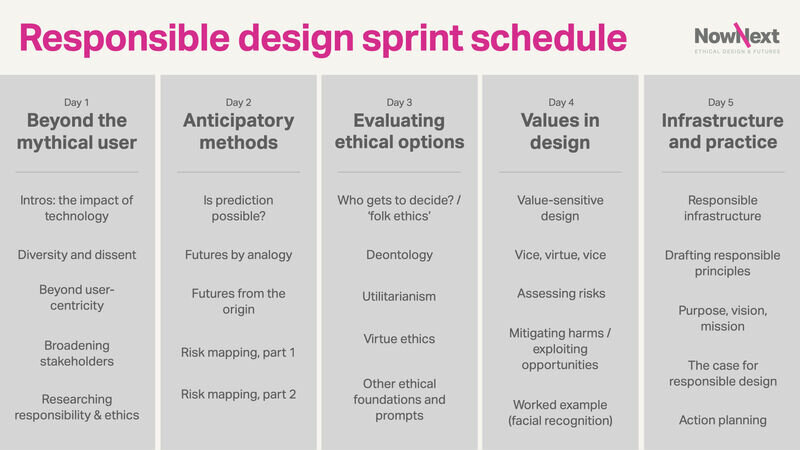

Responsible design sprint overview

Putting the finishing touches on a five-day responsible design training & co-creation sprint. Starts tomorrow. Here’s what we’ll be covering.

If this sounds like just the thing for your team too, let us know.

The limits of ethical prompts

Starting a big project next week, working as a designer-in-remote-residence, helping our client establish and steer a responsible design programme. Lots of planning and prep, including immersing myself in ethics toolkits, card decks, canvases etc to see what we could use.

Some of them are pretty decent, but I’ve found the significant majority are just lists of prompt questions, perhaps grouped into loose categories. Colourful, good InDesign work, but not much content beyond this.

Ethical prompt questions have their place: asking ourselves tricky questions is far better than not asking ourselves tricky questions. But we need to be sceptical of our ability to see our own blindspots. Answers to the question ‘Are we missing something important?’ will – you guessed it – often miss something important.

By all means use toolkits, ask ethical prompts. But be willing to engage with people outside the conference rooms too: people not like us; people more likely to experience the harms of technology. ‘We got ourselves into this mess, so it’s on us to get out of it’ is an understandable view, but can lead to yet more technocracy. Let’s bring the public into the conversation.

Book review: Building for Everyone

One of the most welcome trends in ethical tech is an overdue focus on a wider range of stakeholders and users: a shift from designing at or for diverse groups toward designing with them.

Building for Everyone, written by Google head of product inclusion Annie Jean-Baptiste, has arrived, then, at just the right time. The movement is rightly being led by people from historically underrepresented groups, and I’ve long had the book on pre-order, interested to read the all-too-rare perspectives of a Black woman in a position of tech leadership.

Jean-Baptiste’s convincing angle is that diversity and inclusion isn’t just a matter of HR policy or culture; it’s an ethos that should infuse how companies conceive, design, test, and deliver products. Make no mistake, this is a practitioner’s volume, with a focus on pragmatic change rather than, say, critical race theory. It’s an easy, even quick read.

It’s also a Googley read. While I have a soft spot for Google – or at least I’m easier on it than many of my peers – I find the company to have a curious default mindset: massive yet strongly provincial, the Silicon Valley equivalent of the famous View of the World from 9th Avenue New Yorker cover. True to form, Building for Everyone draws heavily on internal stories and evidence.

Google also has a reputation as an occasionally overzealous censor of employee output, and here the overseer’s red pen bleeds through the pages. The story told is one of triumph: an important grass-roots effort snowballed and successfully permeated a large company’s culture, and here’s how you can do it too. Jean-Baptiste deserves great credit for her role in this maturation and adoption, but the road has been rockier than Building for Everyone is allowed to admit. Entries such as ‘Damore, James’ or ‘gorillas’ – unedifying but critical challenges within Google’s inclusion journey – are conspicuously absent from the index.

This isn’t Jean-Baptiste’s fault, of course. An author who holds a prominent role in tech can offer valuable authority and compelling case studies. The trade-off is that PR and communications teams frequently sanitise the text to the verge of propaganda. Want the big-name cachet? Be prepared to sacrifice some authenticity. The book is therefore limited in what it can really say, and inclusion is positioned mostly as a modifier to existing practices: research becomes inclusive research, ideation becomes inclusive ideation, and so on.

This stance does offer some advantages. It scopes the book as an accessible guide to practical first steps, rather than a revolutionary manifesto. Building for Everyone seeks to urge and inspire, and does so. Jean-Baptiste skilfully argues for inclusion as both a moral and financial duty; only the most chauvinistic reader can remain in denial about how important and potentially profitable this work is.

Nevertheless, this is a book that puts all its chips on change from within. But is that ever sufficient? The downside to repurposing existing tech processes and ideologies is that in many cases those tech processes and ideologies are the problem: they are, after all, what’s led to exclusionary tech in the first place. At what point do we say the baby deserves to be ejected with the bathwater?

We need incrementalist, pragmatic books that win technologists’ hearts and minds, and establish inclusion as non-optional. If that’s the book you need right now, Building For Everyone will likely hit the spot. But we also need fiercer books that take the intellectual fight directly to an uncomfortable industry. Sasha Costanza-Chock’s Design Justice, next on my list, looks at first glance to fill that role, if not overflow it. More on that soon.

New article: ‘Weathering a privacy storm’

I’ve done a lot of privacy design work this year, much of it with my friends at Good Research. I worry many designers and PMs think privacy’s a solved problem: comply with regs, ask for user consent if in doubt, jam extra info in a privacy policy.

Nathan from Good Research and I analysed a recent lawsuit (LA v Weather Channel/IBM) and found privacy notices and OS consent prompts may not be the saviours you think they are. Not only that, but enforcement is now coming from a wider range of sources. Time to take things more seriously.

The Social Dilemma

I watched The Social Dilemma. At its worst moments it was infuriating: deeply technodeterministic, denying almost any prospect of human agency when it comes to technology – pretty much the identical accusation it makes of big tech.

As is common with C4HT’s work, it was either oblivious to or erased (which is worse?) the prior work of scholars, artists etc who warned about these issues long before contrite techies like the show’s stars – and I – came along.

As Paris Marx writes, it teetered on the brink of a bolder realisation, but was too awed by its initial premise to go there. And so it retreated into spurts of regulate-me-daddy centrist cop shit and unevidenced correlation/causation blurring.

But but but. I’m not the audience. I stress in my work that it can’t just be down to the tech industry to solve these problems. We have to engage the public, to explain to them what’s happening in their devices and technological systems. We have to seek their perspectives, request they put pressure on elected officials, and that they force companies to adopt more responsible approaches. If The Social Dilemma does that, perhaps that’s a small gain.

But, oof. If you’re in this field… pour a stiff drink before hitting Play.